VSD. Who came across it?

@Mom_since_this_year Hello everyone! I want to share our story! My pregnancy went well, a couple of times during pregnancy I had a mild cold, I didn’t take any serious medications, everything went away on its own. The ultrasound did not reveal any abnormalities in the fetus. The birth was natural and went well. The nerves started on the second day after the birth of our son. During the rounds, the doctor heard a noise, but then he immediately reassured me that this happens, he will listen again tomorrow. The next day the noise intensified, the baby was scheduled for a heart ultrasound. And then everything was like in a dream, a cardiologist came and announced the diagnosis: congenital heart disease - perimembranous ventricular septal defect 4.5 mm. Tears, fear, reading all the forums, articles that say that these defects do not heal on their own. Four days later we are transferred to the Bashlyaeva Children's Hospital, where we spend three terrible weeks, a specialist from Bakulevka comes there on Wednesdays and does an expert ultrasound, the numbers on the defect that are announced there make me completely depressed - 8.5 mm. There the child is given medications Verashpiron and Digoxin. Three weeks later, they measure a 7.2 mm defect and send us home to register with a cardiologist at the clinic. Also at the hospital we were told that open heart surgery was inevitable before the year was over. While still in the hospital, I made an appointment with cardiologists at the Morozov and Filatov hospitals. At home they continued to give all the medications. First, we arrived for an appointment at the Morozov hospital, where they measured a 5 mm defect on an ultrasound and said that with it there was a chance to wait for surgery in 5 years through an occluder, we exhaled a little. We made an appointment with V.A. Kryukov at the Filatov hospital. he measured 4.5 mm and said that from his experience he thought that our defect should close. Next we made an appointment with M.M. Belyaeva. also at the Filatov hospital, she also measured 4.5 mm, but was not so optimistic in her forecasts. We decided to register with her. And then, first every month, then every two, three months, we went for an ultrasound and each time the defect became smaller. The child was gaining weight well, was active, and did not at all look like he had congenital heart disease. So at 9 months we again went for another ultrasound, which was performed by Yu.Yu. Kornoukhov. and about happiness, the words that all parents dream of hearing, your child is HEALTHY!!! Imagine, HEALTHY! Our defect lasted for 9 months. Everyone congratulated us and sent us home in peace. At the same time, the doctor said that many parents, having heard the same or similar diagnosis, rush to have surgery, but very often such defects are closed and we confirm this! Conclusion: consult several doctors from different clinics, do not rush to make serious decisions if time permits, we were also told that good weight gain in a child has a positive effect on healing. We are 9 months old and weigh 11 kg. And of course, Faith and prayers to God. May all children be healthy.

Isolated ventricular septal defect (VSD)

Ventricular septal defect is the most common congenital heart defect. Defect, i.e. a hole in the septum separating the right and left ventricles is the only violation of the normal development of the heart, and then they speak of an isolated defect or part of another, more complex defect, for example, tetralogy of Fallot. In this section we will only discuss isolated defects.

The interventricular septum is a powerful muscular barrier that forms the internal walls of both the right and left ventricles, and in each it makes up approximately 1/3 of their total area. It is also involved in the process of contraction and relaxation of the heart during each cycle, like the rest of the ventricular walls. In the fetus it is formed from three components. At the 4-5th week of pregnancy, all these components must be accurately matched and connected to each other, as in a Lego constructor. If for some reason this does not happen, a hole or defect remains in the septum. Soon after birth

and the establishment of normal blood flow in both circulations, a significant difference in pressure arises between the left and right ventricles. And then the blood from the left ventricle begins to be pumped simultaneously into the aorta, i.e. where it should be, and through the defect - into the right ventricle, where it should not be. Those. With each systole, a reset occurs from left to right. In such a situation, the right ventricle is forced to work with increased load in order to pump this excess volume, and what’s more, already oxidized blood, back to the lungs and to the left sections.

The amount of discharge depends on the size and position of the defect: it can be small

and have almost no effect on the work of the heart, but can be huge, with a diameter as large as the mouth of the aorta.

Types of ventricular septal defects

A few words about the types of defects. They may be “typical”, i.e. the most common, and occupy the area of the upper part of the septum. They can be muscular, i.e. located closer to the apex, and finally high, under the pulmonary valves, single or multiple (i.e. more than one).

Let's consider the most common and “good” option. The child was born of normal weight, full-term and, of course, very beautiful. But they already told you in the maternity hospital that he has a “heart murmur.” If there or somewhere nearby there is an echocardiography machine and a pediatric cardiologist, it is imperative to do a study to understand what this noise is caused by, whether it is important or not, whether it will affect it in the future .

But let’s assume that the defect was seen on an ultrasound and the diagnosis was made.

The child, however, looks normal, eats well and is gaining weight, is not sick with anything and, in fact, apart from a heart murmur, nothing upsets either you or him. Remember: the louder the noise, the smaller the defect. This is a situation to which the title of W. Shakespeare’s famous play “Much Ado About Nothing” fits perfectly. The release that this noise gives can sometimes even be felt if you place your palm on the left side of the child's chest. But in order to calm down, you need to make sure that the noise is due only to a small defect

of the interventricular septum and nothing else. And for this you need to be observed by a pediatric cardiologist, and an electrocardiogram and ultrasound are taken every three months.

In most cases, approximately 65-75%, such defects close on their own, spontaneously, and if additional symptoms do not appear, you can safely wait 4-5 or even more years. But, if the child has reached school age and remains asymptomatic, then you may nevertheless be offered surgery. The fact is that if a child falls ill with any childhood infection or even with the simple removal of a damaged tooth in the presence of a ventricular septal defect, the development of endocarditis is possible, i.e. inflammatory process of the inner lining of the heart chambers. And, although this probability is very small - only 1-2% of cases, it exists. In this case, the defect is closed for preventive rather than clinical reasons, and no one has proven that this should not be done.

However, before you agree to the operation, in this case, please, without offending anyone

, try to find out what experience is available in the medical institution where you went, what are the results of operations there, what is the degree of risk.

Since the child’s condition is almost normal, and there is always a risk of any intervention, we must calmly weigh everything. No, we are far from urging you to refuse surgery. We just want to advise you to be very thorough, because no one will ever give you written guarantees: an operation is an operation, even if it is performed in an x-ray surgery room (as they will most likely offer you) and complications are always possible, and you will sign a document confirming your agreement. And the final decision is your responsibility.

And one more thing - never suggest to such a child that he has

a bad heart.

Do not protect him from the physical activities available to him,

do not make him a “disabled person.”

Excessive “protection” and prohibitions can lead to the most unfavorable consequences in the formation of his character.

But this is a separate topic, and it concerns not only VSD.

Large defects are another story, much more dangerous. Immediately after the baby's first breath, the blood flow from the left ventricle is divided into two - into the aorta and into the defect, and they are equal in volume! Not only the heart, but also the blood vessels of the lungs find themselves in a difficult situation: the right sections and vessels of the lungs are filled with an increased volume of excess blood entering through the defect. The most important indicators of this development of events are the pressure in the pulmonary artery and the amount of discharge. These data are provided today by ultrasound and, of course, probing of the cavities of the heart. An increase in pressure in the pulmonary circle indicates pulmonary hypertension - the most dangerous consequence of a large discharge from the left to the right. Outwardly everything is more or less working out. Numerous compensation mechanisms are activated: the muscle mass of the ventricles increases, the vessels of the lungs also adapt, first taking in excess blood volume, then thickening the walls of the arteries and arterioles, making them denser and less elastic. This period is dangerous, because... the child's condition may clinically improve significantly, but this improvement is deceptive, and the moment for surgical intervention may be missed. If this situation continues for quite a long time - several months or years, then at some point the pressures in the right and left ventricles are compared in all phases of the cardiac cycle and discharge through the defect no longer occurs

.

And then the pressure in the right ventricle may turn out to be higher

than in the left, and then the so-called “

reverse discharge

” begins, or venous blood will flow through the defect into the arterial system - into the systemic circle.

The patient turns blue.

We painted this picture to make it clear that a defect such as a ventricular septal defect, which is very easy and safe to close in the

early stages

, becomes a defect in which closure loses its meaning, and it is too late to operate.

We are talking here, let us remind you, only about large defects

or about those cases when there are several holes in the partition. Fortunately, this happens much less frequently than most cases.

What should you pay attention to in order to avoid such developments in time?

All of the above applies only to ventricular septal defects, which occur absolutely without complaints, in completely healthy (otherwise) children without any other signs of heart failure. What should you pay attention to with this defect?

The main indicator of the newborn period is weight gain. Let's say an infant eats poorly and therefore gains little weight. His appetite is normal, but due to shortness of breath it is difficult for him to suck, but for now this is his main and rather difficult job. He cries a lot because he can never get enough. In older children, against this background, frequent colds occur, which become prolonged and can develop into pneumonia. This may continue for several months, and if the cause is a VSD, such a child should be under constant supervision of a cardiologist, and if the symptoms do not go away, he will probably receive heart drugs in the form of digoxin or digitalis - the good old drug that improves heart function, and maybe even mild diuretics. He now has signs of heart failure, which can be treated conservatively. But only for now.

When should such a large defect be closed?

With drug therapy, symptoms may go away or significantly decrease. But if nothing changes, if the size of the heart increases and the size of the defect on ultrasound remains the same, you need to contact surgeons.

In the first few months of life, ventricular septal defects, even large ones, may shrink or close on their own. If the child does not get better, you cannot wait, because the situation may turn into the one we described at the beginning, and it will be too late to operate.

The best results

Surgeries occur after the removal of large VSDs at the age of

two to two and a half years

, when the child has signs of heart failure. Then all processes are still reversible. The heart quickly realizes that it is now much easier than before. It quickly decreases in size and blood flow in both circles normalizes.

After the operation, the child is practically healthy and there is no reason to classify him as a member of the group of so-called “disabled children”, as is sometimes done in medical institutions. He can do anything

, and will quickly forget about what happened to him, and except for the scar on his chest, nothing will remind him of it.

So, you are offered an operation, which is now necessary.

and absolutely shown. Only she will heal the child and remove from you the constant feeling of a threat to his life. The operating surgeon will tell you what your case is about and what he or she plans to do. Technical difficulties (for example, the need to close not one, but several defects) can make the operation more complex and lengthy. In an unusual, rare situation, the surgeon will definitely explain everything to you, and your task is to try to understand everything that they tell you, ask the right questions and calm down.

The operation to eliminate a ventricular septal defect is an open

, since it is necessary to open the cavities of the heart, and therefore it is done using artificial circulation.

Ventricular septal defects are closed by suturing the hole (i.e., simply placing several stitches) or, most often, using a patch made of synthetic (or specially treated biological) material, which is quickly covered with the heart’s own tissue.

Nowadays, X-ray surgical methods for closing defects are also used, but this is not always possible; it depends on the anatomical location of the defect, and also on the qualifications of the X-ray surgeon. Traditional surgery for ventricular septal defects is one of the most common and well-established congenital heart defects in surgery, and its results are excellent. So if there is evidence, you don’t need to doubt it.

Radical surgery cannot always be done. In case of a very large defect in a child of too little weight, malnourished, with signs of heart failure that cannot be treated conservatively, the very factor of a major operation with artificial circulation can be dangerous, especially when it comes to children in the first months of life

. And then there is a way out: to break the surgical treatment into two stages - first to help the heart improve its condition, and then to finally close the defect.

It is possible to reduce shunt from the left ventricle to the right by increasing the resistance to right ventricular ejection. By this we will achieve a decrease in pressure in the pulmonary artery system, firstly, below the artificially created obstacle to blood flow, we will equalize the pressure in the right and left ventricles above it (obstacle) and, as a result, the volume of the discharge itself decreases. And this is achieved simply: a cuff is placed on the pulmonary artery above its valves, which will narrow the artery to approximately ½ of the lumen.

An artificially created obstruction to blood flow gives us the desired hemodynamic result. The second operation is performed after a few months, no more. In no case should you wait several years, although the child’s condition may no longer inspire any concern.

However, the postoperative period after surgery to narrow the pulmonary artery is very difficult; children have a hard time with this auxiliary intervention, and that is why we are now striving for a one-stage radical correction of the defect. Even severe children recover from heart failure faster after radical correction of the defect; all life-threatening symptoms gradually disappear.

The operation of narrowing the pulmonary artery is “auxiliary”. It should be in service where there are no conditions for the safe carrying out and nursing of radical corrections to children

.

The final stage of treatment consists of removing this cuff

and

closing the defect

. It is already done under conditions of artificial circulation and is not associated with much risk, especially when a relatively short period of time has passed between it and the first stage.

Summarize. VSD is a common congenital defect that may be accompanied by the early onset of heart failure and the subsequent development of irreversible pulmonary hypertension.

Surgical treatment is the only method and allows you to completely eliminate the defect and its consequences. It must be timely, and the operation itself must be safe. The operation can be elective or urgent, but almost never emergency. In some cases, it can be divided into two stages with an interval of 6-12 months. The appearance of signs of “reverse discharge” in a child with an isolated VSD is a sign of lost time. And with all modern examination methods, such a complication cannot be justified in any way, and part of the blame will fall on you, since you also did not notice or did not want to notice that the moment was missed.

How to get treatment at the Scientific Center named after. A.N. Bakuleva?

Online consultations

Department of Cardiac Surgery and Intensive Care of the Children's Hospital named after. N.F. Filatova

On the one hand, there is a cardiologist who believes that an operation should be performed because he sees indications for this, on the other hand there is a cardiac surgeon who believes that we need to wait a little longer...

I kindly ask specialists in the field of cardiology and cardiac surgery to respond and write their professional opinion about our problem.

On the fourth day of life (in the maternity hospital), my daughter was diagnosed with congenital heart disease: ASD 1 cm. They said that the defect was large, there was almost complete absence of a septum. However, they said that we would watch and that there was a chance that the defect could close or at least decrease. At 5 months, we did another ultrasound of the heart, which showed that the defect had not changed in 5 months. The cardiologist and cardiac surgeon agreed that we will continue to monitor, since there is no deterioration observed. For the next 3 months we lived a normal life: we learned to sit, stand up, talk, gave up breastfeeding, etc... However, we began to notice that the child began to get tired very quickly, began to sweat a lot (when he eats, sleeps, plays, cries and etc., i.e. almost all the time), appetite has deteriorated very much (she stopped eating any complementary foods: no porridge, no puree, and the formula in our current 9 months eats about 100 ml, and then refuses), breathing has become rapid at times (we ourselves and our cardiologist noticed), the skin is pale, sometimes I notice a bluish appearance of the nasolabial triangle, my daughter has practically stopped gaining weight (lately, in order not to lose weight, I have to practically forcefully push porridge into her - at least a little spoons, give the mixture more often; and taking this into account, over the last month we have not gained weight, but have lost 150 grams of weight). At 8 months we again did an ultrasound of the heart. The cardiologist at the clinic saw indications for surgical treatment. However, the cardiac surgeon did not believe these results (not their institution). We had another ultrasound with them. The cardiologist again saw the indications for surgery, but for some reason the cardiac surgeon did not want to perform the operation. He says that there is hope to close the defect with an occluder, and that they perform these operations when the child weighs at least 14 kg. He says to wait until 2-3 years. But the deterioration is obvious! Both the cardiologist and the cardiac surgeon saw them! The heart surgeon said that all negative symptoms and consequences will go away almost immediately after the operation, so he says to wait. He said: “If you tell me “do the operation!”, I won’t go anywhere, I will prepare the documents for the operation and we will do it. But if there is a chance to have surgery using an occluder, then I would wait...” Now I’m completely at a loss. On the one hand, there is a cardiologist who believes that an operation should be performed because he sees indications for this, on the other hand there is a cardiac surgeon who believes that the deterioration is not critical and that we can wait until we gain at least 14 kg. But we hardly eat! Almost no weight gain! Deterioration is visible on ultrasound (including the defect has increased!). What kind of critical deterioration must we wait for before we are sent for surgery? Will we face irreversible consequences (pulmonary hypertension, heart failure, etc.)? What would you recommend in our situation? I am very afraid of missing the opportune moment for surgical treatment of our congenital heart disease. PS The results of the three heart ultrasounds discussed in the message can be viewed in the forum at the following link: https://forum.dearheart.ru/5/19365/ — Sincerely, Katya’s Mom ‹ Large secondary ASD ASD 8 mm ›

Publications in the media

Ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a congenital heart defect with communication between the right and left ventricles.

Etiology • Congenital malformations (isolated VSD, part of a combined congenital heart disease, for example, tetralogy of Fallot, transposition of the great vessels, truncus arteriosus, tricuspid valve atresia, etc.) • There is evidence of autosomal dominant and recessive types of inheritance. In 3.3% of cases, this defect is also found in direct relatives of patients with VSD • Rupture of the interventricular septum due to trauma and MI.

Statistical data • VSD accounts for 9–25% of all congenital heart defects • Is detected in 15.7% of live-born children with congenital heart disease • As a complication of transmural myocardial infarction - 1–3% • 6% of all VSDs and 25% of VSDs in infants are accompanied by a patent ductus arteriosus, 5 % of all VSDs - coarctation of the aorta, 2% of congenital VSDs - aortic valve stenosis • In 1.7% of cases, the interventricular septum is absent, and this condition is characterized as a single ventricle of the heart • The ratio of male to female sex is 1:1.

Pathogenesis. The degree of functional impairment depends on the amount of blood discharge and total pulmonary vascular resistance (TPVR). When shunting from left to right and the ratio of pulmonary minute volume to systemic blood flow (Qp/Qs) is less than 1.5:1, pulmonary blood flow increases slightly, and no increase in PVVR occurs. With large VSDs (Qp/Qs more than 2:1), pulmonary blood flow and pulmonary blood flow significantly increase, and pressures in the right and left ventricles are equalized. As the blood volume increases, the direction of blood discharge may change - it begins to occur from right to left. Without treatment, right and left ventricular failure and irreversible changes in the pulmonary vessels (Eisenmenger syndrome) develop.

Variants of VSD • Membranous VSD (75%) are located in the upper part of the interventricular septum, under the aortic valve and the septal cusp of the tricuspid valve, often close spontaneously • Muscular VSD (10%) are located in the muscular part of the interventricular septum, at a considerable distance from the valves and conduction system , are multiple, fenestrated and often close spontaneously • Supracrestal (VSD of the right ventricular outflow tract, 5%) are located above the supraventricular crest, often accompanied by aortic regurgitation of the aortic valve, do not close spontaneously • Patent AV canal (10%) is found in the posterior part of the interventricular septum, near the site of attachment of the rings of the mitral and tricuspid valves, often found in Down syndrome, combined with ASD of the ostium primum type and malformations of the leaflets and chords of the mitral and tricuspid valves, does not close spontaneously • Depending on the size of the VSD, small ones are distinguished (Tolochinov-Roger disease ) and large (more than 1 cm or half the diameter of the aortic orifice) defects.

Clinical picture

• Complaints: see Atrial septal defect.

• Objectively • Pallor of the skin • Harrison's furrows • Increased apical impulse, trembling in the area of the left lower edge of the sternum • Pathological splitting of the second tone as a result of prolongation of the ejection period of the right ventricle • Rough pansystolic murmur at the left lower edge of the sternum • With supracrestal VSD - aortic diastolic murmur insufficiency.

Instrumental diagnostics

• ECG: signs of hypertrophy and overload of the left parts, and with pulmonary hypertension - also of the right.

• Jugular venography: high-amplitude A waves (atrial contraction with a rigid right ventricle) and, sometimes, V wave (tricuspid regurgitation).

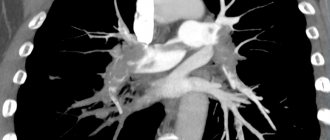

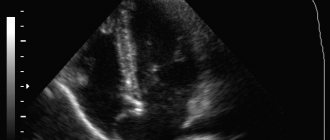

• EchoCG •• Hypertrophy and dilatation of the left parts, and in case of pulmonary hypertension - also the right ones •• Visualization of VSD in Doppler and B-mode •• Diagnosis of associated anomalies (valvular defects, coarctation of the aorta, etc.) •• Determine systolic pressure in the right ventricle , degree of shunt and Qp/Qs •• Transesophageal echocardiography is performed in adults.

• X-ray of the chest organs •• For small VSDs - a normal x-ray picture •• Bulging of the left ventricular arch, increased pulmonary vascular pattern •• With pulmonary hypertension - bulging of the pulmonary artery arch, expansion and lack of structure of the roots of the lungs with a sharp narrowing of the distal branches and depletion of the pulmonary vascular system drawing.

• Radionuclide ventriculography: see Atrial septal defect.

• Catheterization of the cardiac chambers •• Indicated for suspected pulmonary hypertension, before open-heart surgery and in case of conflicting clinical data •• Calculate Qp/Qs •• Tests with aminophylline and oxygen inhalation are performed to determine the prognosis regarding the reversibility of pulmonary hypertension.

• Left ventriculography, coronary angiography: visualization and quantification of shunt, diagnosis of CAD in the presence of symptoms or before surgery.

Drug treatment. With an asymptomatic course and normal pressure in the pulmonary artery (even with large defects), conservative treatment is possible for up to 3–5 years of life. If there is stagnation in the pulmonary circulation, use peripheral vasodilators (hydralazine or sodium nitroprusside), which reduce the discharge from left to right. For right ventricular failure - diuretics. Before and for 6 months after uncomplicated surgical correction of VSD - prevention of infective endocarditis.

Surgery

Indications • Asymptomatic - if spontaneous closure of the defect does not occur by 3–5 years of life, although better results are achieved with surgical treatment before the age of 1 year • Heart failure or pulmonary hypertension in young children • In adults, the Qp/Qs ratio is 1 .5 or more.

Contraindications: see Atrial septal defect.

Methods of surgical treatment. Palliative intervention - narrowing of the pulmonary trunk with a cuff, is performed when emergency surgery is necessary for children weighing less than 3 kg, with concomitant heart defects and little clinical experience in radical correction of the defect at an early age. In case of a traumatic defect in the area of the membranous part of the interatrial septum, suturing of the defect is possible. In other cases, the defect is repaired with a patch made of autopericardium or synthetic materials. In case of post-infarction VSD, plastic surgery of the defect is performed with simultaneous coronary bypass surgery.

Specific postoperative complications: infective endocarditis, AV block, ventricular arrhythmias, recanalization of VSD, tricuspid valve insufficiency.

Forecast. In 80% of patients with large VSDs, spontaneous closure of the defect occurs within 1 month, in 90% - before the age of 8 years, there are isolated cases of spontaneous closure of VSDs between the ages of 21 and 31 years. With small defects, life expectancy does not change significantly, but the risk of infective endocarditis increases (4%). With a medium-sized VSD, heart failure usually develops in childhood, and severe pulmonary hypertension is rare. Large VSDs without a pressure gradient between the ventricles lead to the development of Eisenmenger syndrome in 10% of cases; most of these patients die in childhood or adolescence. Emergency surgical intervention is required in 35% of children within 3 months after birth, 45% within 1 year. Maternal mortality during pregnancy and childbirth with Eisenmenger syndrome exceeds 50%. With post-infarction VSD, 7% of patients survive 1 year in the absence of surgical treatment. Hospital mortality after narrowing of the pulmonary artery is 7–9%, 5-year survival rate is 80.7%, 10-year survival rate is 70.6%. Mortality during surgical treatment of post-infarction VSD is 15–50%. In-hospital mortality during closure of isolated congenital VSD with low LVVR is 2.5%, with high LVVR - less than 5.6%.

Abbreviations. Qp/Qs is the ratio of the pulmonary minute volume of blood flow to the systemic one. TPVR - total pulmonary vascular resistance.

ICD-10 • Q21.0 VSD