Portal vein thrombosis (PVT), or pilethrombosis, is a rarely diagnosed vascular disease of the liver and can be the result of a large number of different diseases, both surgical and therapeutic, remaining asymptomatic for a long period of time, which makes its timely diagnosis difficult. At the same time, the prognosis for PVT is always serious and unfavorable; in half of the cases, deaths are observed due to gastrointestinal bleeding and progression of portal hypertension (PH) [6, 9]. PVT is the process of thrombus formation up to complete occlusion of the lumen of the main trunk and branches of the PVT with progressive impaired blood flow in the liver and gastrointestinal tract.

For the first time, an intravital diagnosis of thrombosis of the main trunk of the venous vein was made by S.P. Botkin. in 1862 [1, 7]. The first description of PVT belongs to Balfur and Stewart (1868) using the example of a patient with splenomegaly, ascites and varicose veins (VV) [1, 3]. In 1934, Strazhesko N.D. Based on his own research and literature data, he developed and described the main symptoms of intravitally recognized PVT [3].

There is no reliable information about the frequency of PVT. Depending on diagnostic methods and patient sampling criteria, statistical data vary greatly. According to autopsy data, in the USA the incidence of portal thrombosis ranges from 0.05 to 0.50% [9, 15]; Data from Japanese pathologists confirm these figures. In the European population, PVT accounts for up to 10% of all cases of PG, while in developing countries this figure reaches 40% [5, 12]. The incidence of PVT in patients with liver cirrhosis (LC), according to various literature data, ranges from 1 to 43% [5, 9]. During liver transplantation, the incidence of PVT varies from 2 to 26% [5].

Thus, the problem of PVT is of great medical importance, especially since there are still no carefully developed algorithms for diagnosing and treating this pathology.

Causes of thrombosis

In order for a blood clot to form in a vein, a number of conditions or factors are necessary. In the classical version, there are three factors that contribute to thrombus formation (Virchow’s triad).

- hypercoagulable state (increased coagulability). There are many reasons for increased blood clotting - surgery on any part of the body, pregnancy, childbirth, diabetes, excess dietary fat, oral contraceptives, dehydration, genetic factors (rare), etc.

- injury to the inner wall of the vessel (endothelium). The vascular wall can be injured during the installation of a venous catheter, injection into a vein (due to this, thrombosis is very common in drug addicts who inject into the veins of the legs, in the groin), injuries, during radiation therapy, chemotherapy, etc.

- slowing down blood flow. It can be observed in various conditions - varicose veins, pregnancy, obesity, immobilization of a limb (for example, when wearing a cast after fractures), heart failure, forced sedentary position of the body (for example, during long air travel), compression of veins by tumors, etc.

Thrombosis can occur due to the action of one factor or a combination of them. For example, in case of a fracture of the leg bones, all three factors can be involved - increased coagulability in the case of extensive hemorrhages in the area of injury, damage to the vascular wall as a result of a mechanical shock, and a slowdown in blood flow as a result of wearing a cast.

Most often, thrombosis occurs in the veins of the lower extremities. This is due to the fact that stagnation most often occurs in these veins (obesity, varicose veins, edema, etc.).

Ultrasonography

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) is increasingly recognized by ultrasound. Abdominal sepsis and decreased portal blood flow resulting from parenchymal liver disease are the main causes.

Figure 8 : Portal vein thrombosis. Longitudinal oblique sonogram of a 36-year-old woman with a history of Leber optic atrophy (hereditary optic neuroretinopathy) and alcohol abuse who had nonspecific complaints of malaise and vague abdominal pain. The image shows ascites and a bright liver (obesity). The portal vein has a linear echogenic structure running along the length of the portal vein (solid arrow). There is a cystic formation in the liver (open arrow).

Figure 9 : Portal vein thrombosis. Power Doppler of the liver shows blood flow around an intraluminal filling defect in the portal vein (P).

Figure 10 : Portal vein thrombosis. A spectral Doppler sonogram of the liver obtained from the same patient as in the previous image shows the portal vein (cursor) which does not demonstrate blood flow.

Figure 11 : Portal vein thrombosis. A longitudinal oblique sonogram was obtained from a 28-year-old woman who was referred for a gallbladder ultrasound. The image shows several vascular tubular structures at the porta hepatis, which are suggestive of cavernous transformation.

Figure 12 : Portal vein thrombosis. A color Doppler sonogram obtained from the same patient as in the previous image shows blood flow in the cavernous mass.

Figure 13 : Portal vein thrombosis. Color Doppler ultrasound of the spleen obtained from the same patient as in the previous 2 images shows mild splenomegaly with splenic varices. Endoscopic findings confirmed the presence of esophageal varices.

Figure 14 : Color Doppler ultrasound depicts a vascularized portal thrombus.

Figure 15 : Color Doppler ultrasound depicts a vascularized portal thrombus.

Figure 16 : Echoic partially recanalized portal vein thrombus. The patient is a 36-year-old woman with idiopathic chronic portal vein thrombosis of 2 years duration. She has cholestatic jaundice.

Sonograms may show echogenic lesions in the portal vein. A clot with variable echogenicity may be depicted. The clot is usually moderately echogenic, but if it has recently formed, it may be hypoechoic.

Patent vessels may have increased intraluminal echogenicity due to the accumulation of red blood cells, making slow blood slightly echogenic. Increased or decreased echogenicity may be observed in the lumen of the portal vein.

PVT eliminates the normal venous flow signal from the portal vein lumen during pulsed or color Doppler ultrasound. Color Doppler flow images can show flow around a clot that is partially blocking a vein. However, if the flow is slow, the Doppler signal may not be detected. Color flow may be present in other small collateral vessels.

Incomplete occlusion may occur. This is typical for tumor lesions. Alternatively, thrombolytic recanalization may occur. Cavernous malformations, spontaneous shunts, splenorenal and portosystemic collaterals can also be detected. The underlying cause may be obvious: hepatocellular carcinoma, metastases, cirrhosis, pancreatic neoplasms.

It is assumed that the thickening of the portal vein with a narrowing of its lumen is caused by portal phlebitis. This is considered a precursor to PVT in patients with acute pancreatitis. The diameter of the portal vein is greater than 15 mm in 38% of cases of PVT.

Superficial vein thrombosis

ATTENTION! Deep vein thrombosis is dangerous due to the detachment of a blood clot and its migration into the pulmonary artery (pulmonary embolism), which most often leads to serious consequences or instant death!

Superficial veins are affected by thrombosis most often with varicose veins. Blockage of the vessel is accompanied by inflammation of the surrounding tissues. That is why the terms “thrombophlebitis” (phlebitis - inflammation of a vein), “varicothrombophlebitis” (inflammation of varicose veins) are used for this type of thrombosis.

Usually, in the area of varicose veins on the lower leg, pain and redness appear along the vein; in the area of redness, the vein itself is palpated as a dense, painful “cord”. There may be a slight increase in body temperature. In general, thrombophlebitis of the superficial veins is not dangerous; there is no detachment of a blood clot with pulmonary embolism (with the exception of inflammation of the great saphenous vein on the thigh and the small saphenous vein in the popliteal region, this will be discussed below). With adequate treatment, the inflammatory phenomena subside, and the patency of the veins is partially or completely restored over time.

The great saphenous vein (GSV) runs under the skin from the ankle joint along the inner surface of the leg to the groin fold. In the groin it flows into the deep femoral vein. That is why thrombophlebitis of the GSV is dangerous due to the transition of thrombosis from the superficial (GSV) to the deep (femoral) vein - ascending thrombophlebitis of the GSV. But thrombosis of the femoral vein is dangerous due to the detachment of a blood clot and pulmonary embolism. Therefore, if there are signs of GSV thrombosis (redness, pain along the inner surface of the thigh), you should urgently consult a surgeon or call an ambulance. Such patients are hospitalized and, if there is a threat of thrombosis spreading to the femoral vein, the GSV is ligated closer to the groin - this is a simple operation under local anesthesia.

A similar situation, but much less frequently, occurs with thrombophlebitis of the small saphenous vein (SSV). It runs along the back of the leg and drains into the popliteal (deep) vein in the popliteal fossa.

Treatment of PVT

Management of patients with PVT depends on the onset of the disease (acute or chronic), clinical presentation, etiological factors leading to PVT, age and other factors. Complications of PVT - ascites, bleeding from PVT - are treated in the same way as for cirrhosis with PG.

In acute PVT, anticoagulant therapy is recommended, which leads to complete or partial restoration of the PVT lumen in 70–80% of patients [5, 12, 15].

Spontaneous thrombus lysis in PVT is possible, but is very rare. Anticoagulant therapy does not increase the risk of bleeding, but it reduces the risk of intestinal infarction, which is life-threatening. The recurrence rate of PVT varies from 6 to 40% [2, 21], so some authors recommend anticoagulant therapy for 6 months [10, 21].

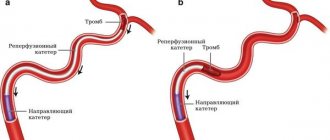

Thrombolysis through a transhepatic approach for acute PVT is a method that avoids the side effects of systemic anticoagulant therapy. Thrombolysis can also be carried out systemically, especially in cases of acute total or subtotal occlusion of IVs [9, 10].

Unfortunately, there is still no clear practical guidance on the prescription of anticoagulants in patients with PVT. How to choose the right anticoagulant? What doses should be used? When to stop anticoagulant therapy? What contraindications exist for the use of anticoagulants? Large randomized trials are needed to answer these questions.

Surgical treatments include transhepatic angioplasty, thrombolysis followed by transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), thrombectomy with local fibrinolytic infusion. If the patient is planning to undergo shunting, it is preferable to perform distal splenorenal shunting [5, 10]. Splenectomy should be avoided, since it itself is an etiological factor in the development of PVT. The main methods of medical and surgical treatment of PVT are presented in Table. 2.

. Basic methods of treating PVT.

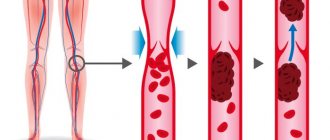

Deep vein thrombosis

Deep vein thrombosis is a more severe disease, usually requiring the patient to remain in the hospital.

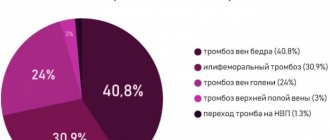

There are deep vein thrombosis of the leg, popliteal vein, femoral vein, iliofemoral (ileofemoral) thrombosis. Often there is damage to thrombosis of several sections (for example, the popliteal and femoral veins, deep veins of the leg and popliteal vein, etc.).

Deep vein thrombosis manifests itself primarily as swelling and moderate pain. Moreover, the higher the level of thrombosis, the more pronounced the edema. Thus, with thrombosis of the deep veins of the leg, there may be moderate swelling of the leg, sometimes the swelling is so insignificant that it is detected only when measuring the circumference of the leg (compared to the healthy leg). With thrombosis of the femoral or iliac (continuation of the femoral) veins, the entire leg, up to the groin, and in severe cases, the lower part of the abdominal wall swells.

In the photo - the left lower limb is cyanotic, thickened to the groin - deep vein thrombosis at the level of the iliofemoral segment (ileofemoral thrombosis).

Thrombosis, as a rule, is unilateral, so only one leg swells. Bilateral edema is observed with thrombosis of the inferior vena cava, deep vein thrombosis in both legs (which is quite rare).

Another symptom of thrombosis is pain. It is usually moderately expressed, pulling, sometimes bursting, is relatively constant in nature, and can intensify in a standing position. In case of deep vein thrombosis of the leg, the Homans, Lowenberg, Luvellubri, Meyer, Payra symptoms are positive.

With deep vein thrombosis, there may also be a slight increase in temperature, increased venous pattern, etc.

Practical Basics

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) is increasingly recognized by ultrasound. Decreased portal blood flow caused by liver parenchymal disease and abdominal sepsis (ie, infectious or ascending thrombophlebitis) are the main causes.

PVT is a common complication of liver cirrhosis, and its prevalence increases with the severity of liver disease, ranging from 1% in patients with compensated cirrhosis to 8–25% in liver transplant candidates.

Correct diagnosis and characterization of PVT are important for prognosis and further treatment. Portal vein thrombosis is a poor prognostic indicator, found at diagnosis in 10-40% of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Survival is approximately 2-4 months.

CEUS allows detailed visualization of the hepatic microvasculature, focal liver lesions, and portal vein thrombosis. Malignant thrombi have the same pattern of enhancement as the tumor from which they originated, including rapid arterial phase elevation and slow or weak washout in the portal vein.

Treatment of thrombophlebitis of superficial veins

The main therapeutic measures are reduced to elastic compression (elastic bandage or compression hosiery) and the prescription of medications.

Medicines used include phlebotropic drugs (detralex, phlebodia), antiplatelet agents (thrombo-ACC), and anti-inflammatory drugs (Voltaren). Lyoton-gel is applied topically.

All patients require venous ultrasound to exclude concomitant deep vein thrombosis and clarify the prevalence of superficial vein thrombophlebitis.

Treatment of deep vein thrombosis

In almost all cases, deep vein thrombosis is treated in a hospital. An exception may be deep vein thrombosis of the leg, provided there is no threat of thromboembolism. The danger of thromboembolism can only be determined by ultrasound examination.

If deep vein thrombosis is suspected, the patient should be hospitalized immediately. In the hospital, an examination is carried out to clarify the prevalence of thrombosis, the degree of threat of pulmonary embolism, and treatment is started immediately.

Anticoagulants (anticoagulants), antiplatelet agents, anti-inflammatory drugs, and phlebotropic drugs are usually prescribed.

In case of massive thrombosis, in the early stages it is possible to carry out thrombolysis - the introduction of agents that “dissolve” thrombotic masses.

If there is a threat of thromboembolism, when the thrombus is attached to the vessel wall only in some part, and the tip of the thrombus “dangles” in the lumen of the vessel (floating thrombus), thromboembolism is prevented (installation of a vena cava filter, plication of the inferior vena cava, ligation of the femoral vein, etc. ).

The consequences of deep vein thrombosis vary. With a small thrombosis on the lower leg there may be no consequences. With massive thrombosis, especially “high” (at the level of the hip or above), swelling of the leg may persist for a long time, and in severe cases there may be trophic disorders, even the appearance of ulcers (post-thrombophlebitic disease (PTSD)). Therefore, after deep vein thrombosis, the patient is prescribed treatment for a long time in the form of elastic compression (special stockings), indirect anticoagulants (warfarin under the control of blood clotting), and other drugs.

You should see a phlebologist for at least six months after thrombosis.

In case of recurrent thrombosis, a genetic study is carried out; if the tests are positive, the issue of lifelong prescription of anticoagulants is decided.

Diagnosis of PVT

The need to use imaging studies is determined by the lack of specific signs of PVT and the need to identify the level of venous outflow impairment. The main diagnostic methods in this case are ultrasound (US) and Doppler studies, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and angiography.

Ultrasound can detect PVT only when areas of increased echogenicity caused by the presence of blood clots are visualized in the lumen of the PVT. With an increase in the size of the PV, one can only assume PG, i.e. this sign is not diagnostic. Detection of venous collaterals more reliably confirms the diagnosis of PG.

Doppler ultrasound makes it possible to identify the structure of the PV and hepatic artery. The diagnostic value and results of the study depend on the experience of the physician and the quality of the analysis of image details. The greatest difficulty is in studies of cirrhotic livers and in overweight patients [2, 19]. With color Doppler mapping (CDC), the quality of PVT visualization improves. Technically correctly performed colorectal dizziness allows diagnosing ventricular obstruction as reliably as angiography. With CDK it is possible to identify natural intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. This is the cheapest, most effective and non-invasive method. Its high sensitivity and specificity are observed in patients with extensive thrombotic lesions and complete closure of the vascular lumen. At the same time, the presence of residual blood flow along the IV increases the likelihood of a technical error when assessing the results of the study [5, 19].

In order to reduce the risk of such errors when diagnosing PVT, duplex ultrasound scanning is used to determine the velocity of portal blood flow. This method combines Doppler ultrasound scanning with traditional ultrasound, which allows the doctor to see the structure of the blood vessels. Duplex scanning shows the movement of blood through the vessels and allows you to measure the speed of blood flow. This method also allows you to determine the diameter of blood vessels and identify their blockage. The most modern and accurate imaging methods include CT, venography and MRI.

CT can provide information about the condition of the vessel walls, liver damage (for example, with the formation of cavernous nodes) and show the extent of thrombosis [5, 15].

After administration of a contrast agent, it becomes possible to determine the lumen of the venous veins and identify ventricular veins located in the retroperitoneal space, as well as perivisceral and paraesophageal veins. The esophageal esophagus bulges into its lumen, and this bulge becomes more noticeable after the administration of a contrast agent.

CT in combination with arterial portography makes it possible to identify collateral blood flow pathways and arteriovenous shunts. Portography through the internal jugular vein is an invasive but very accurate diagnostic method. It allows you to assess the extent of thrombosis, its exact location and the severity of thrombotic stenosis of the PV.

MRI allows you to very clearly visualize and study blood vessels. This method is used to determine the lumen of shunts, as well as to assess the consistency of portal blood flow. MRI results are more reliable than Doppler ultrasound data [5, 15, 19].

Venography is used to verify the diagnosis in cases where the above-described research methods do not clearly confirm or exclude the suspected PVT. At the same time, if the patency of the vein is established by any method, confirmation of this using venography is not mandatory. Venography also makes it possible to detect defects in the filling of the PV or its branches, indicating external compression by a space-occupying formation [5].

In clinical practice, for the diagnosis of portal thrombosis, two methods are usually combined to overcome the disadvantages of each of them. When diagnosing PVT, you should pay attention to the coagulogram: an increase in fibrinogen content, the appearance of activated fibrinogen, an increase in the prothrombin index, a decrease in blood clotting time.

Causes of thrombosis in the superior vena cava system

The causes of thrombosis in the superior vena cava system are basically the same as other venous thrombosis. It may also develop as a complication of venous catheterization (cubital, subclavian catheter), sometimes arising as a result of prolonged compression or uncomfortable position of the upper limb (for example, during sleep).

The most common is thrombosis of the axillary or subclavian vein (Paget-Schrötter syndrome). Within 24 hours, swelling of the entire upper limb occurs with cushion-like swelling of the hand. There may be slight bursting pain. The color of the limb is unchanged or slightly cyanotic.

BB system

The PV system includes all the veins that carry out the outflow of venous blood from the intra-abdominal part of the gastrointestinal tract, spleen, pancreas and gall bladder (see figure).

. Anatomical structure of the portal vein system. S. Sherlock, J. Dooley.

The PV is formed from the confluence of the superior mesenteric and splenic veins behind the head of the pancreas at approximately the level of the second lumbar vertebra; the length of the PV at the hepatic portal is 5.5–8.0 cm. At the porta hepatis, the PV is divided into the right and left lobar branches, corresponding to the lobes of the liver; further in the liver, the AV is divided into segmental branches accompanying the branches of the hepatic artery.

The BB does not contain valves in the main branches. The distribution of portal blood flow in the liver is not constant: blood flow to the left or right lobe of the liver may predominate. In humans, it is possible for blood to flow from the system of one lobar branch to the system of another. The pressure in a person's ventricular vein is normally about 7 mm Hg. Art. The volumetric velocity of blood flow through IVs reaches 1000–1200 ml/min [3].

Etiology and pathogenesis of PVT

According to modern concepts, venous thrombosis is the cumulative result of congenital or acquired procoagulant disorders and the action of local factors [10, 22].

A condition in which the balance between the processes of coagulation and fibrinolysis is disturbed in favor of coagulation processes can be defined as thrombophilia. A person with congenital or acquired thrombophilic disorders during life more often than in the normal population develops arterial or venous thrombosis of various locations (Table 1) [5, 11,12, 14, 23].

The Leiden mutation in the factor V gene occurs in 2–4% of the European population and leads to a change in the amino acid sequence of coagulation factor V itself (replacement of arginine with glutamine at position 506). Mutated factor V is resistant to destruction by protein C; constant circulation of activated factor V leads to uncontrolled synthesis of thrombin and the formation of blood clots [11, 13, 16, 23].

The mutation of the coagulation factor II gene was first described in 1996, occurs in the general population in 2% of the population and leads to excessive generation of prothrombin, i.e., a shift in hemostasis to the procoagulant side [17, 22].

Protein C is synthesized in the liver through a vitamin K-dependent mechanism and is a natural anticoagulant. Protein S is a cofactor of protein C, involved in the neutralization of active forms of coagulation factors V and VIII. Currently, about 160 mutations of the protein C gene and many mutations of the protein S gene have been described, which leads to a deficiency of these proteins and the development of thrombophilia [11].

Acquired blood coagulation disorders can occur in myeloproliferative diseases, antiphospholipid syndrome; they also accompany inflammatory and oncological diseases and are observed during the use of oral contraceptives [16, 22, 23], pregnancy and hyperhomocysteinemia. In 60% of patients with thrombosis of the veins of internal organs, hypercoagulation is observed, in 25% the influence of local factors is of paramount importance [16, 20] . PVT is characterized by a combination of causative factors [18, 20]. In approximately 20% of cases, the development of thrombosis does not find an exhaustive explanation [21]. The occurrence of thrombosis is promoted by all diseases that occur with a slowdown in blood flow through the liver.

The pathogenesis of PVT in cirrhosis is not fully understood. PH, a decrease in the rate of blood flow through IVs, and peripheral lymphangiitis and fibrosis may be important here [20].

. Causes of thrombophilia.