1.General information

The rheumatic group of diseases is united by a common etiopathogenesis and affected “targets”: there is a systemic pathology of connective tissue affecting the whole organism and an associated inflammatory process, usually in large joints. However, the most dangerous consequence of the rheumatic process is damage to the myocardium, which always occurs with rheumatism - to varying degrees of severity (according to the well-known and very accurate medical saying, “rheumatism licks the joints and bites the heart”). In some cases, rheumatic inflammation occurs in the form of acute fever, which, after relief of the main symptoms, is complicated by the formation of a specific heart defect. This refers to damage and disruption of the complex valvular biomechanics of the myocardium, which normally ensures its uninterrupted pumping function. In such cases they talk about chronic rheumatic heart disease (CRHD).

The problem is very serious throughout the world for a number of reasons. Firstly, rheumatic heart disease is quite widespread: in WHO statistics it ranks fourth among all cardiovascular diseases. Secondly, CRHD is one of the main factors of high mortality in this category. Thirdly, rheumatic heart disease usually develops in children, adolescents and young adults, i.e. affects the most promising, active and able-bodied part of the population, often leading to disability and “excluding” this sample from social functioning (at least, sharply limiting its activity and reducing the quality of life).

A must read! Help with treatment and hospitalization!

Publications in the media

Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) is a systemic inflammatory disease of connective tissue involving the heart and joints in the pathological process, initiated by group A β-hemolytic streptococcus, occurring in genetically predisposed people. The term rheumatism, widely used in practice, is currently used to designate a pathological condition that combines acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease.

Statistical data . Incidence: 2.1 per 100,000 population in 2001. The incidence of rheumatic heart disease in Russia is 0.17%. The predominant age is 8–15 years. Etiology. -Hemolytic streptococcus of group A, “rheumatogenic” serotypes M3, M5, M18, M24. The M protein on the streptococcal membrane has antigenic determinants similar to components of the heart muscle, brain and synovial membranes.

Genetic aspects . Ag D8/17 B-lymphocytes are detected in 75% of patients with ARF. Pathogenesis • Antistreptococcal antibodies are responsible for selective damage to the heart valves and myocardium with the development of immune aseptic inflammation, cross-reacting with heart tissue (molecular mimicry) • M-protein has the properties of a “superantigen” that causes activation of T- and B-lymphocytes without preliminary processing of Ag- presenting cells and interactions with class II molecules of the major histocompatibility complex.

Clinical picture • Onset of the disease. In more than half of the cases, 2–4 weeks after a streptococcal nasopharyngeal infection, fever, asymmetric joint pain, pain in the heart, shortness of breath, and palpitations occur. In other patients, the onset occurs as a monosyndrome (carditis, arthritis or chorea) • A repeated attack occurs with symptoms of carditis.

• Arthralgia and rheumatic polyarthritis (80% of patients) - typical reactive synovitis with fluid effusion into the joint cavity, swelling and redness of the periarticular tissues, sometimes with severe pain, tenderness and limitation of active and passive movements. Characteristic features:

•• damage to large joints (knee [most often], ankle, elbow, shoulder and much less often - wrist) •• symmetry of the lesion •• migrating, volatile nature of arthritis •• complete reversibility of the articular syndrome, no changes on radiographs, restoration of joint function • • in children, signs of arthritis, as a rule, completely disappear, and in adults a persistent course can be observed, leading to the development of Jaccoud's syndrome (painless deformation of the hands with ulnar deviation without inflammation in the joints and without dysfunction of the joint) •• with rheumatism, more often with repeated attacks, polyarthralgia rather than arthritis often occurs.

• Fever (90%). • Subcutaneous nodules (10% of patients), grain to pea-sized, localized in the periarticular tissues may appear during acute rheumatic fever. These nodules do not bother patients, they are painless, and the skin over them is not changed. Involution of the nodules occurs over a period of several days to several weeks. Observed only in children.

• Ring-shaped erythema - pale pinkish-red spots up to 5-7 cm in diameter with clear, not always smooth edges. Characterized by localization on the skin of the chest, abdomen, back and limbs, spontaneous disappearance and (rarely) recurrence. Occurs in less than 5% of patients. Erythema nodosum is not typical for rheumatism. • Chorea occurs in 10–15% of patients, more often in girls, 1–2 months after a streptococcal infection. It is chaotic involuntary twitching of the limbs and facial muscles. Characteristic is the complete disappearance of symptoms during sleep. • Rheumatic carditis (rheumatic carditis) can be primary (first attack) and recurrent (repeated attacks), with or without the formation of valve disease. Clinical symptoms of rheumatic carditis: •• Cardialgia . Characterized by prolonged stabbing, aching pain in the heart area, usually without irradiation. With pericarditis, pain is associated with breathing and intensifies in a horizontal position. •• In most cases an enlarged heart , which is not always detected physically. A chest x-ray is recommended. •• Arrhythmias as a manifestation of myocarditis ••• Sinus tachycardia (100 or more per minute), recorded at rest ••• Atrial fibrillation occurs, as a rule, when signs of mitral valve stenosis appear ••• Ventricular (rare) or supraventricular extrasystoles •• • Atrioventricular block with prolongation of the P-Q interval over 0.2 s or the appearance of Wenckebach (Samoilov-Wenckebach) periods. •• Decrease in sonority of the first tone at the apex of the heart, appearance of the third tone and murmurs. A gentle blowing systolic murmur with a tendency to increase in intensity and conducted into the axillary region is a symptom of mitral valvulitis. Protodiastolic murmur along the left sternal border is a sign of aortic valvulitis. •• Signs of congestive heart failure are rarely observed with primary rheumatic carditis; much more often they accompany recurrent rheumatic carditis. • Acute rheumatic fever lasts 6–12 weeks. There is no chronic or continuously relapsing course.

Laboratory data • Increased ESR, increased titers of antistreptolysin O, AT to DNase in a titer of more than 1:250 • Bacteriological examination of a throat smear reveals group A -hemolytic streptococcus. Instrumental data • ECG • Chest X-ray • EchoCG. Differential diagnosis • Reactive arthritis • Lyme disease • Infective endocarditis • Viral (Coxsackie B) myocarditis • Mitral valve prolapse • Functional heart murmur. Kissel-Jones-Nesterov diagnostic criteria (revised 1992) • Major criteria: •• carditis •• polyarthritis •• chorea •• annular erythema •• subcutaneous nodules • Minor criteria: •• clinical symptoms (fever, joint pain) • • laboratory changes (increased ESR, appearance of CRP, prolongation of the P–Q interval •• Additional signs: positive cultures from the tonsils for group A β-hemolytic streptococcus, increased titers of antistreptolysin-O and/or other antistreptococcal antibodies. The presence of two large or one large and two minor criteria in combination with the mandatory presence of additional signs allows us to consider the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever reliable.Despite the presence of time-tested criteria, the diagnosis of ARF continues to be a problem, since individual criteria (fever, ESR, etc.) are not specific, and subcutaneous nodules and Annular erythema is rarely observed.

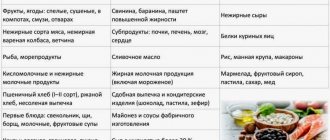

TREATMENT Management tactics . For acute rheumatic fever, hospitalization, bed rest, and a diet low in salt and rich in vitamins and protein are indicated. The basis of drug treatment is antibacterial and anti-inflammatory therapy. Drug treatment • Antibacterial therapy •• Benzylpenicillin 1.5–4 million units/day for adolescents and 400–600,000 units/day for children for 10–14 days, followed by a transition to benzathine benzylpenicillin or benzathine benzylpenicillin + benzylpenicillin procaine •• When if you are allergic to penicillins, you should choose a macrolide: roxithromycin for children 5–8 mg/kg/day, adults 150 mg 2 times/day, clarithromycin for children 7.5 mg/kg/day, adults 250 mg 2 times/day. It should be remembered that streptococcal resistance to erythromycin is currently increasing. • NSAIDs for 3.5–4 months (during treatment it is necessary to periodically conduct blood tests, urine tests, and liver function tests) •• Diclofenac 50 mg 3 times a day. • The use of GC is most justified for pancarditis. One of the treatment regimens is prednisolone 20–30 mg/day until clinical effect, then gradually reducing the dose over 20–30 days.

Prevention • Primary prevention : rational treatment of streptococcal diseases of the oropharynx for 10 days •• Aminopenicillins ••• amoxicillin 750 mg/day for children, 1500 mg/day for adults •• Cephalosporins ••• cephalexin for children with body weight <40 kg - 25– 50 mg/kg/day, adults 250–500 mg 2–4 times/day (daily dose 1–2 g) ••• cefaclor children 20 mg/kg 3 times/day, adults 750 mg 3 times/day ••• cefuroxime for children 125–250 mg 2 times a day, adults 0.25–0.5 g 2 times a day •• Macrolides ••• roxithromycin for children 5–8 mg/kg/day, adults 150 mg 2 times a day days •• Penicillins with β-lactamase inhibitors ••• amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (adults 375 mg 3 times / day) for 10 days. • Secondary prevention is indicated for patients who have had acute rheumatic fever to prevent relapses. The best results are achieved by year-round bicillin prophylaxis (benzathine benzylpenicillin 600,000–1,200,000 units (children), 2,400,000 units (adults) once every 3 weeks. Benzathine benzylpenicillin + benzylpenicillin procaine 1,500,000 units once every 10–12 days. D duration of secondary prophylaxis •• at least 5 years after the last reliable rheumatic attack for patients who have had acute rheumatic fever without carditis •• more than 5 years - for patients who have had rheumatic carditis •• with relapses for life • Prevention of infective endocarditis against the background of formed rheumatic heart disease with carrying out any surgical interventions (tooth extraction, abortion, abdominal surgery) - see Infectious endocarditis.

Synonym . Sokolsky-Buyo disease. Abbreviations. ARF - acute rheumatic fever.

ICD-10 • I00 Rheumatic fever without mention of cardiac involvement • I01 Rheumatic fever with cardiac involvement

2. Reasons

Almost all available sources name the main (or only) cause of rheumatic heart disease as experienced acute rheumatic fever - various variants of rheumatic carditis, i.e. rheumatic inflammation of certain structural elements of the heart. In turn, the acute development of cardiac rheumatism is associated with the pathogenic activity of hemolytic streptococcus. However, in special publications one can find data that from 30% to 50% of patients do not have such episodes in their history. Even if we assume that some acute rheumatic fevers were simply not diagnosed or recorded, the percentages are too high to speak about the complete clarity of the causes of chronic rheumatic heart disease.

Risk factors usually include being female, frequent respiratory infections against the background of general immune weakness, heredity, and systematic long-term stay in cold rooms with high humidity.

Visit our Cardiology page

Rheumatism

Terminology

Rheumatism is one of those diseases that everyone knows about or, at least, has heard of.

However, prevailing ideas about rheumatism vary very widely: from the childhood fear of sneakers (“You can’t always walk in them - you’ll catch a cold and get rheumatism!”) to a more adult discovery: it turns out that rheumatism affects not the legs, but the heart. A careful study of available sources sometimes only confuses the situation. In fact, how can we understand a disease in which it is not a single organ or even a functional system that suffers, but an entire type of tissue in the body? However, this is exactly what happens with rheumatism. Rheumatism is an inflammatory-immune lesion of connective tissue, which is present almost everywhere in the body.

The definition of “inflammatory-immune” should be used in this order: first inflammation, then an immune reaction to it, and then an autoimmune attack on one’s own connective tissue. This is akin to what a brave, fast, but not very accurate bodyguard can do, continuing to shoot in bursts after the invasion has long been repulsed...

As a rule, the connective tissue structures of the heart, joints, blood vessels, and subcutaneous layers are affected. Much less common (1-6 percent of the total volume of registered rheumatism) are rheumatic lesions of the central nervous system, respiratory and visual organs, and gastrointestinal tract.

Rheumatism does not show any endemicity (regional dependence of epidemiological indicators): people get sick everywhere. However, there is a clear dependence of morbidity on age - among primary patients, the category of 5-15 years predominates - as well as an inverse correlation with the standard of living of the population. Considering that the majority of children on the globe (up to 80%) live in the so-called. developing countries, one should not be surprised at the widespread prevalence of rheumatism in the “third world”.

In the last quarter of a century, morbidity and mortality in Russia have decreased by more than three times. However, if we are talking about such a serious disease, and even with a predominantly early manifestation, no epidemiological data can be considered “satisfactory”, except zero. Today, statistics are contradictory and are mainly of an evaluative nature (and this applies not only to the Russian Federation): as a rule, data from the 1960s-90s are extrapolated to the current situation. A more or less reliable estimate of the incidence among Russian children can be considered a frequency of 2-3 cases per 10,000 (and over 1.5% of all heart defects are rheumatic); for comparison, in third world countries this figure varies from 60 to 220 per 10,000.

In conclusion of a brief general overview, it should be noted that the term “rheumatism” itself is currently used mainly by Russian-speaking medicine. In the official international lexicon these are “Acute rheumatic fever”, “Rheumatic heart disease”, “Rheumatoid arthritis”, etc.; however, code M79.0 (heading “Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue”) in ICD-10 indicates “Rheumatism, unspecified.”

3. Symptoms, diagnosis

There are several variants of valve disease that causes CRHD. In some cases, the failure consists of incomplete closure, in others there is a narrowing of the lumen (stenosis) and, accordingly, a decrease in valve capacity; a combined defect is said to occur when the first two anomalies are present simultaneously; about combined – with defects of two or more valves.

For a long time (up to several years), chronic rheumatic heart disease can be mild or asymptomatic; sometimes it is diagnosed accidentally during examination for other reasons. However, with the increase in valvular incompetence, weakness and fatigue, a characteristic blush with a cyanotic tint and cyanosis of the fingers, shortness of breath, cough, episodes of night suffocation, and swelling of the lower extremities appear. Patients often complain of pain in the liver, which turns out to be enlarged upon examination. Many patients report increased heart palpitations and heart pain during physical activity, periodic dizziness, lightheadedness and/or fainting.

Correct diagnosis of CRHD requires not only a careful examination and detailed collection of complaints, but also a thorough examination of the medical history. Standard auscultation and percussion are informative; electrocardiographic and echocardiographic studies are additionally prescribed (including in Doppler mode to assess the capacity of large vessels).

About our clinic Chistye Prudy metro station Medintercom page!

DAMAGE OF THE HEART AND VESSELS in rheumatoid arthritis

When mitral stenosis is detected in a patient with RA, it is always necessary to exclude its rheumatic etiology, since the combination of RA with a previous rheumatic defect is recognized by many authors. A pathogmonic sign of rheumatoid arthritis are rheumatoid nodules in the myocardium, pericardium and endocardium at the base of the mitral and aortic valves, in the area of the fibrous ring

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease of connective tissue with progressive damage to predominantly peripheral (synovial) joints of the type of symmetrical erosive-destructive polyarthritis with frequent extra-articular manifestations, among which heart damage, according to autopsy data, is noted in 50-60% of cases [ 1, 4, 7]. Changes in the heart in RA have recently been classified as the articular-cardiac form of the disease. When joints are affected, when physical activity is noticeably reduced, cardiac pathology is often masked, which requires the doctor to more carefully and thoroughly examine the patient. At the same time, clinical changes in the heart are, as a rule, minimal and rarely come to the fore in the overall picture of the underlying disease. Systemic manifestations of RA, including cardiac damage, determine the overall prognosis, so their early recognition and targeted treatment are important.

Morphological picture

| Figure 1. Interstitial myocarditis, mild vasculitis. Env. hematoxylin and eosin. X 150 |

The frequency of myocardial damage in RA in the form of myocarditis is not clear. This is due, on the one hand, to the difficulty of diagnosing myocarditis in people with limited motor activity, and on the other hand, to the lag of clinical manifestations from morphological changes in the heart [6, 7]. Myocardial pathology is polymorphic in nature due to the presence of vascular lesions of varying duration [7]. Some vessels have vasculitis, others have hyalinosis, and others have sclerosis. The nature of vasculitis can be proliferative and rarely proliferative-destructive. The inflammatory infiltrate is dominated by lymphohistiocytic elements both in the perivascular space (Fig. 1) and in the vascular wall. It should be noted that when the main process is activated, a combination of old and fresh vascular changes is observed. Along with this, focal or diffuse interstitial myocarditis occurs, ending in the development of small-focal cardiosclerosis. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis often develop brown myocardial atrophy with accumulation of lipofuscin in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2). These changes may cause angina. A pathogmonic sign of rheumatoid arthritis are rheumatoid nodules in the myocardium, pericardium and endocardium at the base of the mitral and aortic valves, in the area of the fibrous ring. As a result of the nodule, sclerosis develops, causing the formation of valve insufficiency. Myocarditis manifests itself and is diagnosed, as a rule, at the height of the activity of the main rheumatoid process, that is, with the next pronounced exacerbation of the articular syndrome.

Clinic

| Figure 2. Interstitial myocarditis. Lipofuscin deposits in perinuclear spaces. Env. hematoxylin and eosin. X 400 |

The leading complaint in myocarditis at the onset of cardiac damage is discomfort in the heart area (cardialgia), unexpressed, prolonged, diffuse and without clear localization, as a rule, without irradiation and not relieved by nitrates. The main complaints include palpitations, irregular heartbeats and, less commonly, shortness of breath during exercise. Doctors usually associate rapid fatigue, excessive sweating and low-grade fever with another exacerbation of RA, and not with cardiac pathology [3].

During auscultation, physical data reveal tachycardia and weakening of the first sound with systolic murmur; it is often possible to listen to the third sound. As a rule, myocarditis in RA is not prone to progression, and there are no signs of heart failure [4].

ECG data

With a routine ECG examination, a decrease in T waves, lowering of ST intervals, and slight disturbances in intraventricular conduction may be observed. These changes are nonspecific and can accompany various diseases. Slowing of atrioventricular conduction, which is more typical for myocarditis, is rare.

The literature describes a significant number of observations where cardiac arrhythmias are the only pathological symptom of coronary artery damage. Rhythm and conduction disturbances in active RA are much more often detected with 24-hour ECG monitoring and transesophageal electrophysiological studies than with a conventional ECG. So,

I. B. Vinogradova [2] in a study of patients with RA using the above technique revealed rhythm and conduction disturbances in 60% of patients, including atrial (18%) and ventricular (10%) extrasystole, paroxysmal tachycardia (4%), atrial fibrillation arrhythmia (6%), transient right bundle branch block (20%) and second degree atrioventricular block (2%). It has also been suggested that ST depression detected by transesophageal electrophysiological study is an indirect sign of changes in the coronary microcirculation due to rheumatoid vasculitis. Therefore, these patients had high levels of circulating immune complexes, rheumatoid factor, and antibodies to cardiolipin Ig M. It is important to note that in the same group of patients there were other signs of vasculitis: digital arteritis, livedo reticularis, Raynaud's syndrome and rheumatoid nodules. Consequently, if routine clinical research methods do not reveal sufficiently convincing signs of rheumatoid myocarditis, then modern electrophysiological studies reveal facts of cardiac dysfunction, which indicates the connection of these changes with the activity of the rheumatoid process. This can be confirmed by the positive dynamics of changes under the influence of adequate treatment of the underlying disease, usually noted with regression of the articular syndrome.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of myocarditis and myocardial dystrophy, often carried out in patients with RA who have been receiving massive drug therapy for a long time, is difficult, since the clinical manifestations in both cases are similar [5, 6]. The presence of myocarditis will be confirmed by the positive dynamics of its manifestations under the influence of correctly selected and prescribed antirheumatic treatment in adequate doses.

| Figure 3. Pericardial thickening. Sclerosis. Env. hematoxylin and eosin. X 150 |

Pericarditis is the most common cardiac lesion in RA [1]. Pathologically, it is detected in the vast majority of cases in the form of fibrous, less often hemorrhagic pericarditis; often detection of characteristic rheumatic granulomas. A distinctive feature of pericarditis in rheumatoid arthritis is the participation in inflammation of large basophilic histiocytes under the area of fibrinous overlays. Deeper granulation tissue is formed, containing lymphocytes and plasma cells, with thickening of the pericardium and the formation of rough sclerosis (Fig. 3).

The patient may complain of pain in the heart area of varying intensity and duration. The frequency of clinical diagnosis of pericarditis varies (20-40%) and depends mainly on the thoroughness of the clinical examination of the patient and the level of competence of the clinician. In most cases, adhesions in the pericardial cavity and thickening of the latter due to a sclerotic process, often recurrent, are anatomically determined. The effusion is usually small, without signs of tamponade. It is confirmed, as a rule, by X-ray data indicating blurred and uneven contours of the heart. Pericardial friction sounds are not constant and are not heard in all patients, although in some cases they remain for a long time in the form of pericardial clicks in various phases of the cardiac cycle, which is recorded by a qualitative FCG study. ECG changes in most patients are nonspecific for pericarditis. But in the event of the appearance of even moderate exudate, a decrease in QRS voltage can be observed with positive dynamics as the effusion decreases. Pericarditis in RA is prone to recurrence. In some cases, pericarditis is accompanied by the appearance of concordant negative T waves on many ECG leads, which can lead to an erroneous diagnosis of myocardial infarction. Echocardiography is of great importance in detecting RA pericarditis, as it allows identifying changes in the pericardium (its compaction, thickening, presence of fluid) and the dynamics of these changes during repeated studies. In many cases, ECHO changes in pericarditis are an unexpected finding for both the patient and the attending physician [8].

Endocarditis in RA is observed much less frequently than pericarditis. Pathological data indicate frequent involvement of the endocardium, including the valve endocardium, in the form of nonspecific inflammatory changes in the leaflets and valve ring, as well as specific granulomas. In most patients, valvulitis proceeds favorably, does not lead to significant deformation of the valves and does not have significant clinical manifestations. However, in some patients, the course of valvulitis may be complicated by deformation of the valves and be accompanied by severe insufficiency of the affected valve, most often the mitral valve, which dictates the need for surgical correction of the defect. Typically, endocarditis is combined with myocarditis and pericarditis. The possibility of the formation of stenoses of the mitral and aortic valves is discussed in the literature, but there is no consensus on this issue [6]. When mitral stenosis is detected in a patient with RA, it is always necessary to exclude its rheumatic etiology, since the combination of RA with a previous rheumatic defect is recognized by many authors [4].

In order to study the nature of valvular heart pathology in RA, the results of treatment of 297 patients with definite RA according to the APA criteria were analyzed. The analysis showed that most often - in 61.6% of cases - mitral regurgitation occurs. Moreover, in 17.2% of patients it was moderate or severe. In 152 (51.2%) patients, a polyprojection ECHO-CG study did not reveal structural changes in the valve leaflets. A more detailed analysis made it possible to allocate 14 patients who had a history of rheumatism and rheumatic heart disease into a separate group. These patients developed RA 1–24 years before the study (on average 8.9 years). 7 of them had characteristic signs of rheumatic mitral stenosis (severe in 3) in combination with mitral regurgitation of varying severity and signs of aortic disease, which in 1 patient was diagnosed as combined. In 2 patients, mitral disease was in the form of moderate mitral insufficiency and was combined with aortic valve insufficiency. In 3 patients, signs of rheumatic mitral valve insufficiency were revealed. In 2 patients there was a pronounced combined aortic defect in combination with relative mitral valve insufficiency.

Thus, our data confirm the possibility of RA disease in persons who previously suffered from rheumatism and have rheumatic heart defects.

A separate group included 38 patients (average age 58.7 years, duration of RA 12.8 years) with the presence of structural changes in the valvular apparatus of the heart in the form of total marginal thickening of the leaflets or individual foci of thickening, often reaching large values (13x6 mm), signs calcification and limited mobility of the valves. The cusps of the mitral ring were changed in 19, the aortic - in 33, the tricuspid - in 1 patient, and in 16 patients there were combined changes in the mitral and aortic valves, in 1 - in the mitral and tricuspid. In 17 of 19 patients, structural changes in the mitral valves were accompanied by mitral regurgitation.

In 17 of 33 patients with changes in the aortic valves, aortic regurgitation was diagnosed, while in 12 it was moderate or severe. In 16 patients, including 2 with signs of calcification, there was sclerosis of the aortic valves without dysfunction of the valve, which was confirmed by unchanged transaortic blood flow. In 1 patient with significant thickening of the valves and moderate aortic regurgitation, there was a limitation of their opening (1-2 cm) and an increase in the transaortic pressure gradient, i.e., signs of aortic stenosis. And another 33-year-old patient was diagnosed with a congenital bicuspid aortic valve with signs of moderate aortic regurgitation. Severe tricuspid regurgitation was diagnosed in 3 patients with focal thickening of the tricuspid cusps, and in 1 of them cor pulmonale was diagnosed as a complication of rheumatoid lung disease.

The question arises: are all the detected changes in this group of 33 patients a consequence of RA? Analysis of our data showed that the majority of patients in this group were aged 51–74 years. 19 of them were diagnosed with arterial hypertension and had signs of coronary heart disease, 4 patients suffered a myocardial infarction, 1 suffered an acute cerebrovascular accident. The results of the study showed that in individuals with high blood pressure, changes in the valve apparatus were more pronounced, and only they were diagnosed with calcification of the mitral valve and/or aortic valve, signs of aortic regurgitation, hypertrophy of the left ventricular wall and interventricular septum, as well as thickening of the aortic walls with signs of dilatation and diastolic dysfunction of the left ventricle. The detected ECHO-CG changes in this group of patients do not differ from those in atherosclerotic cardiosclerosis, aortic atherosclerosis and are classic. Therefore, in this group of patients it is not possible to exclude the atherosclerotic genesis of heart defects. At the same time, it is likely that rheumatoid valve damage itself can serve as a favorable background against which pronounced structural changes in the valves subsequently develop, the pathology of which dominates both in the clinical and in the ECHO-CG picture of atherosclerotic damage to the heart valves. In each case, the question of the genesis of the defect in RA requires taking into account all available clinical data.

Literature

1. Balabanova R. M. Rheumatoid arthritis. In the book: Rheumatic diseases (guide to internal diseases) / Ed. V. A. Nasonova and N. V. Bunchuk. - M.: Medicine, 1997. P. 257-295. 2. Vinogradova I. B. Cardiac rhythm and conduction disturbances in patients with rheumatoid arthritis // Abstract of thesis. dis. ...cand. honey. Sci. M., 1998. P. 21. 3. Eliseev O. M. Amyloidosis of the heart // Ter. arch. 1980. No. 12. P. 116-121. 4. Kotelnikova G. P. Heart damage in rheumatoid arthritis // In: Rheumatoid arthritis. - M.: Medicine, 1983. P. 89-90. 5. Kotelnikova G.P., Lukina G.V., Muravyov Yu.V. Cardiac pathology in secondary amyloidosis in patients with rheumatic diseases // Klin. rheumatol. 1993. No. 2. P. 5-8. 6. Nemchinov E. N., Kanevskaya M. Z., Chichasova N. V. et al. Heart defects in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (results of a long-term prospective clinical echocardiographic study) // Ter. arch. 1994. No. 5. P. 33-37. 7. Radenska-Lopovok S. G. Morphological methods of research and diagnosis in rheumatology In the book: Rheumatic diseases (manual of internal diseases), ed. V. A. Nasonova and N. V. Bunchuk. M.: Medicine, 1997. pp. 80-94. 8. Tsurko V.V. Aseptic necrosis of the femoral heads in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical and instrumental diagnostics and outcomes: Abstract. dis. ...Dr. med. Sci. M., 1997. P. 50

4.Treatment

Therapeutic regimens may vary significantly depending on the clinical characteristics of a particular case. The most general principles include the prescription of antiarrhythmic and antihypertensive drugs, cardiac glycosides, anticoagulants - in general, the primary task is to unload the valve(s) affected by rheumatic inflammation and prevent thrombosis.

However, even with a competent and adequate therapeutic strategy, chronic rheumatic heart disease can be aggravated by further complications: progression of heart failure, thromboembolism (including in the blood supply to the brain, i.e., ischemic stroke develops), exacerbations of smoldering rheumatic myocarditis, etc. P.

If conservative treatment is ineffective and/or an alarmingly rapid increase in heart failure is observed, they resort to one of the methods of cardiac surgical correction (usually the question of valve replacement is raised).

Acquired heart defects

Acquired heart defects are classified according to the following criteria:

- Etiology: rheumatic, due to infective endocarditis, atherosclerotic, syphilitic, etc.

- Localization of the affected valves and their number: isolated or local (if 1 valve is affected), combined (if 2 or more valves are affected); defects of the aortic, mitral, tricuspid valves, pulmonary artery valve.

- Morphological and functional damage to the valve apparatus: stenosis of the atrioventricular orifice, valve insufficiency and their combination.

- The severity of the defect and the degree of disturbance of the hemodynamics of the heart: not having a significant effect on intracardiac circulation, moderate or pronounced.

- State of general hemodynamics: compensated heart defects (without circulatory failure), subcompensated (with transient decompensation caused by physical overload, fever, pregnancy, etc.) and decompensated (with developed circulatory failure).

Left atrioventricular valve insufficiency (mitral regurgitation)

In case of mitral insufficiency, the bicuspid valve does not completely close the left atrioventricular orifice during left ventricular systole, resulting in regurgitation (backflow) of blood into the atrium. Mitral valve insufficiency can be relative, organic and functional.

The causes of relative insufficiency in this heart defect are myocarditis, myocardial dystrophy, leading to weakening of the circular muscle fibers that serve as a muscle ring around the atrioventricular opening, or damage to the papillary muscles, the contraction of which helps in systolic closure of the valve. With relative insufficiency, the mitral valve is not changed, but the hole it covers is enlarged and, as a result, is not completely blocked by the leaflets.

The leading role in the development of organic failure is played by rheumatic endocarditis, which causes the development of connective tissue in the leaflets of the mitral valve, and subsequently - wrinkling and shortening of the leaflets, as well as the tendon threads connected to it. These changes lead to incomplete closure of the valves during systole and the formation of a gap, which promotes the reverse flow of part of the blood into the left atrium.

With functional insufficiency, the functioning of the muscular apparatus that regulates the closure of the mitral valve is disrupted. Also, functional failure is characterized by regurgitation of blood from the left ventricle into the atrium and often occurs when the mitral valve prolapses.

In the stage of compensation with slight or moderate mitral valve insufficiency, patients do not complain and do not differ in appearance from healthy people; Blood pressure and pulse were not changed. Mitral heart disease can remain compensated for a long time, however, as the contractility of the myocardium of the left parts of the heart weakens, stagnation increases, first in the pulmonary and then systemic circulation. In the decompensated stage, cyanosis, shortness of breath, palpitations appear, and later - swelling in the lower extremities, painful, enlarged liver, acrocyanosis, swelling of the veins of the neck.

Narrowing of the left atrioventricular orifice (mitral stenosis)

With mitral stenosis, the cause of damage to the left atrioventricular (atrioventricular) orifice is usually long-term rheumatic endocarditis, less often stenosis is congenital or develops as a result of infective endocarditis. Stenosis of the mitral orifice is caused by fusion of the valve leaflets, their compaction, thickening, and shortening of the chordae tendineae. As a result of the changes, the mitral valve takes on a funnel-shaped shape with a slit-like opening in the center. Less commonly, stenosis is caused by scar-inflammatory narrowing of the valve ring. With prolonged mitral stenosis, the valve tissue may become calcified.

There are no complaints during the compensation period. With decompensation and the development of stagnation in the pulmonary circulation, cough, hemoptysis, shortness of breath, palpitations and irregularities, and pain in the heart appear. When examining the patient, attention is drawn to acrocyanosis and a cyanotic blush on the cheeks in the shape of a “butterfly”; in children there is a lag in physical development, “heart hump”, and infantilism. With mitral stenosis, the pulse on the left and right arms may differ. Since significant hypertrophy of the left atrium causes compression of the subclavian artery, the filling of the left ventricle decreases, and, consequently, the stroke volume decreases - the pulse on the left becomes small in filling. Often, with mitral stenosis, atrial fibrillation develops; blood pressure is usually normal; less often, a slight tendency to decrease systolic and increase diastolic pressure is observed.

Aortic valve insufficiency

Aortic valve insufficiency (aortic insufficiency) develops when the semilunar valves, which normally close the opening of the aorta, do not close completely, resulting in blood flowing from the aorta back into the left ventricle in diastole. In 80% of patients, aortic valve insufficiency develops after rheumatic endocarditis, much less often as a result of infective endocarditis, atherosclerotic or syphilitic lesions of the aorta, or trauma.

Morphological changes in the valve are determined by the cause of the development of the defect. With rheumatic lesions, inflammatory and sclerotic processes in the valve leaflets cause them to shrink and shorten. With atherosclerosis and syphilis, the aorta itself can be affected, expanding and retracting the leaflets of the unchanged valve; Sometimes the valve leaflets are subject to cicatricial deformation. The septic process causes the disintegration of parts of the valve, the formation of defects in the valves and their subsequent scarring and shortening.

Subjective sensations with aortic insufficiency may not appear for a long time, since this type of heart defect is compensated by increased work of the left ventricle. Over time, relative coronary insufficiency develops, manifested by sensations of tremors and pain (angina-like) in the heart area. They are caused by sharp hypertrophy of the myocardium and deterioration of blood supply to the coronary arteries with low pressure in the aorta during diastole.

Frequent manifestations of aortic insufficiency are headaches, pulsation in the head and neck, dizziness, orthostatic fainting as a result of impaired blood supply to the brain with low diastolic pressure.

Further weakening of the contractile activity of the left ventricle leads to stagnation in the pulmonary circulation and the appearance of shortness of breath, weakness, palpitations, etc. On external examination, pale skin and acrocyanosis are noted, caused by unsatisfactory blood supply to the arterial bed in diastole.

Sharp fluctuations in blood pressure in diastole and systole cause pulsation in the peripheral arteries: subclavian, carotid, temporal, brachial, etc. and rhythmic shaking of the head (Musset's symptom), changes in the color of the nail phalanges when pressing on the nail (Quincke's symptom or capillary pulse), narrowing pupils in systole and dilation in diastole (Landolfi's symptom).

The pulse in aortic valve insufficiency is fast and high due to the increased stroke volume of blood entering the aorta during systole and high pulse pressure. Blood pressure with this type of heart disease is always changed: diastolic is reduced, systolic and pulse are increased.

Aortic stenosis

Narrowing or stenosis of the aortic mouth (aortic stenosis, narrowing of the aortic opening) during contractions of the left ventricle prevents the expulsion of blood into the aorta. This type of heart defect develops after rheumatic or septic endocarditis, with atherosclerosis, or a congenital anomaly. Aortic stenosis is caused by fusion of the aortic semilunar valve leaflets or cicatricial deformation of the aortic orifice.

Signs of decompensation develop with a pronounced degree of stenosis of the aortic opening and insufficient release of blood into the arterial system. Violation of the blood supply to the myocardium leads to the appearance of angina-type pain in the heart; decreased blood supply to the brain - headaches, dizziness, fainting. Clinical manifestations are more pronounced during physical and emotional activity.

Due to unsatisfactory blood supply to the arterial bed, the patients’ skin is pale, the pulse is small and rare, systolic blood pressure is reduced, diastolic blood pressure is normal or increased, and pulse pressure is reduced.

Right atrioventricular valve insufficiency (tricuspid regurgitation)

With tricuspid heart disease, organic and relative insufficiency of the right (tricuspid) atrioventricular valve can develop. The causes of organic failure are rheumatic or septic endocarditis, injuries accompanied by rupture of the papillary muscle of the tricuspid valve. Isolated tricuspid insufficiency develops extremely rarely; it is usually combined with other valvular heart defects.

Organic failure is caused by dilatation of the right ventricle and stretching of the right atrioventricular orifice; often combined with mitral heart defects, when due to high pressure in the pulmonary circulation the load on the right ventricle increases.

With tricuspid valve insufficiency, pronounced congestion in the venous system of the systemic circulation causes the appearance of edema and ascites, sensations of heaviness in the right hypochondrium, and pain associated with hepatomegaly. The skin is bluish, sometimes with a yellowish tint. The neck and liver veins swell and pulsate (positive venous pulse syndrome). The pulsation of the veins is associated with the reflux of blood from the right ventricle back into the atrium through the atrioventricular opening that is not blocked by the valve. Due to blood regurgitation, the pressure in the atrium increases, and emptying of the hepatic and jugular veins is difficult.

The peripheral pulse usually does not change or becomes frequent and small, blood pressure is reduced, central venous pressure increases to 200-300 mm water column.

As a result of prolonged venous stagnation in the systemic circulation, tricuspid heart disease is often accompanied by severe heart failure, dysfunction of the kidneys, liver, and gastrointestinal tract. Pronounced morphological changes are observed in the liver: the development of connective tissue in it causes so-called cardiac fibrosis of the liver, leading to severe metabolic disorders.

Combined and associated heart defects

Among acquired heart defects, especially those of rheumatic origin, there is often a combination of defects (stenosis and insufficiency) of the valve apparatus, as well as simultaneous, combined damage to 2 or 3 heart valves: aortic, mitral and tricuspid.

Among the combined heart defects, the most frequently detected are mitral valve insufficiency and mitral orifice stenosis with a predominance of signs of one of them. Combined mitral heart disease early manifests itself as shortness of breath and cyanosis. If mitral regurgitation prevails over stenosis, then blood pressure and pulse remain almost unchanged; otherwise, a small pulse, low systolic and high blood pressure are determined.

The cause of combined aortic heart disease (aortic stenosis and aortic insufficiency) is usually rheumatic endocarditis. The signs characteristic of aortic valve insufficiency (increased pulse pressure, vascular pulsation) and aortic stenosis (slow and small pulse, decreased pulse pressure) are not so pronounced in combined aortic disease.

Combined damage to 2 or 3 valves is manifested by symptoms typical for each defect individually. In case of combined heart defects, it is necessary to identify the predominant lesion to determine the possibility of surgical correction and further prognostic assessments.