Causes of coronary artery stenosis

The main cause of stenosis is atherosclerosis, in which cholesterol deposits accumulate on the walls of blood vessels, gradually forming plaques that block the lumen.

Also among the provoking factors include:

- anomalies in the development of coronary vessels (tortuosity, incorrect location);

- cardiomyopathy;

- endarteritis;

- systemic diseases (vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis);

- benign and malignant tumors;

- heart transplantation.

Increase the risk of vasoconstriction:

- hereditary predisposition;

- hypertension;

- diabetes;

- pathologies of the thyroid gland;

- excess weight;

- sedentary lifestyle;

- smoking;

- frequent stress;

- elderly age.

Causes

There is no consensus in modern medicine regarding the causes of atherosclerosis of the heart vessels. There are a number of indirect reasons that influence the development of pathology:

- increased blood cholesterol levels due to poor diet;

- sedentary lifestyle;

- overweight and obesity;

- diseases of the heart and cardiovascular system;

- infectious diseases;

- hormonal disorders;

- diabetes;

- heredity;

- unfavorable psychological environment;

- use of tobacco, alcohol and drugs.

Symptoms of coronary artery stenosis

The main sign of narrowing of the coronary arteries is discomfort, burning and pain in the heart area that occurs during physical and emotional stress. There may be burning pain lasting from 30 seconds to 10 minutes, radiating to the shoulder blade and left arm.

Clinical manifestations may include:

- attacks of dizziness;

- increased heart rate;

- heart rhythm disturbance;

- increased blood pressure;

- shortness of breath;

- weakness.

In some cases, the disease is asymptomatic for a long time and manifests itself only when the vessel is completely blocked by a thrombus or atherosclerotic plaque, which causes ischemia and myocardial infarction. Heart attack is the leading cause of death (90%) from heart disease.

Usually the heart experiences oxygen starvation when the lumen is blocked by 51%. If the artery narrows by 75%, then any physical activity can cause a heart attack, accompanied by necrosis of cardiac tissue. But due to the individual characteristics of the body, some people feel a deterioration in their condition already at 44%, while others do not notice changes even with a narrowing of 75%.

“Senile” heart disease: truth and myths

What is hidden behind the diagnosis of “atherosclerotic aortic stenosis”? What is the mechanism of development of aortic stenosis? Is there a difference in treatment tactics in Russia and abroad?

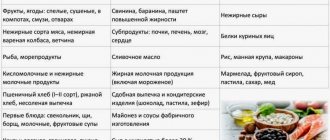

| Picture 1 |

Many therapists and cardiologists are well aware of this frequently occurring clinical phenomenon: in an elderly person without a rheumatic history, when listening to the heart, a rough systolic murmur is detected over the aortic points.

Often it is practically not interpreted in any way and is not reflected in the diagnosis. But sometimes, in an attempt to explain such an auscultatory picture, the doctor still makes something like this verdict: “atherosclerotic stenosis of the aortic mouth.” But we must not forget that a diagnosis is a formula for treatment, and further tactics largely depend on how correctly it is formulated. This applies to any diagnosis, and this one in particular. That is why it is necessary to seriously understand not only and not so much the validity of the term “atherosclerotic stenosis”, but what actually hides behind a “non-rheumatic” systolic murmur at the base of the heart. In the USSR, three main causes of acquired aortic stenosis were traditionally considered: 1) rheumatism, 2) infective endocarditis and 3) atherosclerosis. It was this triad, and, as a rule, in exactly this order, that migrated from manual to manual, from one textbook to another until the middle of this decade, while other prerequisites were given a place in the “and others” column. Most authors, after describing rheumatic and “septic” endocarditis in one form or another, mention atherosclerosis, which usually in old age can lead to the formation of calcified stenosis of the aortic valve [1].

Meanwhile, people abroad have held a different point of view for more than 30 years. It is consistently discussed in English-language sources published in the 60s, 70s and 80s, and the last decade is no exception. According to Western researchers, aortic stenosis in adults can be the result of: 1) calcification and dystrophic changes of the normal valve, 2) calcification and fibrosis of the congenital bicuspid aortic valve, or 3) rheumatic damage to the valve, with the first situation being the most common cause of aortic stenosis [2] .

So, there is an obvious difference in approaches to this problem in Russia and abroad. The “crossing point” was and remains only rheumatism, while domestic and foreign schools each “supplement” it with two different etiological forms: the first - infective endocarditis and atherosclerosis, the second - idiopathic calcification and calcification of a congenital defect (usually the bicuspid valve). But keep in mind that there are two caveats. Firstly, isolated calcification of both the tricuspid and bicuspid aortic valves is essentially the same process, observed only in different time ranges. Secondly, infective endocarditis, by the work of modern authors, is actually excluded from the list of significant causes of aortic stenosis. Thus, by and large, there remain two conditions that determine diagnostic, therapeutic and methodological discrepancies: atherosclerosis and idiopathic calcinosis. The fundamental difference between these two pathological conditions will become clear after a more detailed consideration of senile calcification of the aortic mouth as an independent nosological form.

- Morphological aspects

In 1904, in the journal Archives of Pathological Anatomy, 28-year-old German physician Johann Georg Menckeberg described two cases of aortic stenosis with significant calcification of the valves [3]. He proposed to consider changes in the valves as degenerative, as a result of tissue wear followed by their “sclerosis” and calcification. Having apparently discovered something similar to what is shown in Fig. 1, he depicted in his article a deformed valve, in which, against the background of fatty degeneration, there are many calcareous deposits (Fig. 2). His correctness will be confirmed many years later, which will be reflected in the very term “degenerative calcified aortic stenosis.” But at the beginning of the century, I. G. Menkeberg’s article did not cause a significant resonance. And only after a decade and a half it will become the object of attention and form the basis of heated discussions that have been going on for a long time. The morphogenesis of the defect also caused a lot of controversy.

| Figure 2 |

Mainly two theories competed with the Mönckeberg hypothesis: atherosclerotic lesions and post-inflammatory calcification.

In our country, the atherosclerotic hypothesis has acquired primary importance. It is believed that a detailed study of “atherosclerosis of the aortic valve” in the dynamics of the development of “atherosclerotic defect” was carried out by Professor A.V. Walter in the late 40s. He described intense lipoid infiltration of the fibrous layer of the valve at the level of the closing line and at the bottom of the sinuses of Valsalva, and he also observed lipoid deposition on the sinus surface of the valves in small thickenings of the subendothelial layer. Next, petrification of lipomatous lesions took place. The calcareous masses split, which the researcher explained by the mobility of the valves, and the resulting cracks are filled with plasma proteins and new portions of lipoids, in which calcium is again deposited. The splitting of petrification continues, and after this the calcification of the valve continues. The fibrous ring becomes rigid, the valves are hard and inactive. Aortic stenosis develops [4].

It seems that in 1948 the publication of these data was enough to substantiate the atherosclerotic hypothesis, although even the very idea of “splitting” of petrified masses requires critical reflection: if it had taken place, the frequency of microembolic complications would probably have increased significantly. Today, when knowledge about atherogenesis is much more extensive, it seems possible to put forward at least two counterarguments to the theory of A.V. Walter.

- It is now known that the main anatomical substrate that requires lipids for metabolism is the myocyte. It is smooth muscle cells that utilize substances transported into the arterial wall by plasma lipoproteins. The predominant damage by atherosclerosis to the inner, rather than the middle layer of the vascular wall is explained by the fact that normally in old age the intima thickens due to the movement of smooth myocytes into it from the media with subsequent proliferation. In other words, the intima owes much of its infiltration of cholesterol esters to smooth muscle cells. So, these are the ones that are practically absent in the leaflets of the aortic valves. Modern histologists point to this [5], this was mentioned in 1904 by Menkeberg himself.

- According to the current theory, atheromorphogenesis includes three stages: fatty streaks or spots, fibrous plaques and, finally, complicated lesions, which include calcification of the fibrous plaque. That is, the stage of calcification in atherosclerosis must be preceded by a stage when extracellular cholesterol mixed with detritus appears under the lens, covered with a special visor of a large number of smooth myocytes, macrophages and collagen. Professor A.V. Walter did not describe anything like this. And not by chance. In 1994, that is, almost 50 years after the publication of Walter’s work, V.N. Shestakov describes the morphogenesis of this defect as follows: “The initial phase of this process is lipoid infiltration of the valve surfaces facing the sinuses of Valsalva. In areas of lipoidosis, deposition of calcium salts begins. This process slowly progresses, leading to limited mobility of the valves” [6]. As can be seen, these observations are fundamentally similar, and both lack the fibrous plaque stage. In addition, as American scientists have long proven, in the pathology we are discussing, in contrast to atherosclerotic damage, there are no cholesterol crystals [7]. As far as can be judged from English-language periodicals, there is also no correlation between calcified aortic stenosis and the severity of general atherosclerotic lesions, including the aorta itself in a given patient.

The line under these considerations can be summed up with an excerpt from an article on atherosclerosis by Professor E. Bierman at the University of Washington: “It should not be confused with atherosclerosis <...> local calcifying lesion of the aortic valve, when with age there is a gradual accumulation of calcium on the aortic surface of the valve” [8].

The post-inflammatory hypothesis, widespread mainly in the West, suggested looking for a connection between calcification and a history of infective endocarditis, or, more likely, latent rheumatic carditis. Thus, some researchers point to the presence of microbial agents in calcium conglomerates [9]. Others report the results of a histological examination of 200 calcified aortic valves, 196 of which showed signs of rheumatic lesions [10]. Now it is difficult to give an objective assessment of such data, but, probably, these were sectional finds in people who were not so elderly and without pronounced calcareous deposits. These are the conclusions you come to when studying the opinion of modern pathologists, who claim that in old patients the massiveness of petrification always masks the signs, perhaps, of a history of rheumatic endocarditis.

However, the approach that emerged in the first half of the century led to the formation of two views that are now prevalent abroad. One of them suggests that rheumatic valvulitis, even without leaving persistent granulomatous lesions, makes the valve more vulnerable in the future, significantly increasing the risk of structural degeneration [11] and allowing senile aortic stenosis to be considered truly “degenerative”, whereas post-inflammatory dystrophy, post-rheumatic degeneration; at the same time, the transferred inflammation seems to determine the connective tissue destruction of the valves in old and senile age, turning out to be a kind of predictor of calcification of the aortic valve apparatus. According to another view, senile calcified stenosis is not so much the result of infective endocarditis, but can itself be caused by an infectious pathogen that persists in the aortic valves [12], that is, we are generally talking about a completely independent nosological form.

The uniqueness of the pathology under consideration is also evidenced by the fact that more and more often there are publications about the discovery of various bone tissue cells and even elements of red bone marrow in the calcified cusps of the aortic valve [13].

- Clinical aspects

The reminder of the well-known signs of aortic stenosis to the medical audience in this case is not accidental. The fact is that in elderly and elderly patients, doctors are often inclined to explain the presence of certain complaints more likely by coronary disease or general involutive processes in the body, rather than by a mature “senile” heart defect. Therefore, briefly about the main features of this disease.

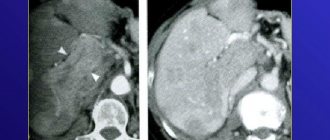

| Figure 3 |

Aortic stenosis is one of the most long-term compensated defects due to myocardial hypertrophy, which is as severe as can be found in other heart diseases (Fig. 3). In this regard, the end-diastolic pressure in the left ventricle increases significantly, its filling (especially during physical activity and in conditions of tachycardia) becomes more difficult, which gradually leads to an increase in the wedge pressure of the pulmonary artery. The shortness of breath that develops, thus, at first turns out to be a consequence of primary diastolic dysfunction of the left ventricle, and during the period of decompensation - also of systolic dysfunction. Increased myocardial tone in diastole is also associated with impaired oxygenation. While the increase in left ventricular mass increases the myocardial oxygen demand, the compressed coronary arteries cannot satisfy it. Hence the angina pain that is so typical for this category of patients. Moreover, although angina occurs in 70% of patients with aortic stenosis, only half of them have coronary atherosclerosis [2]. The third common complaint - fainting - is a consequence of a decrease in cardiac output, which develops as a result, on the one hand, of a decrease in diastolic filling of the ventricle, and on the other, an increasing pressure gradient at the level of the aortic valve [14]. Dizziness can be equivalent to syncope.

Among the complications of senile stenosis, embolism with crumbling calcareous masses (most often of the coronary, renal and cerebral arteries), poorly tolerated and prognostically unfavorable arrhythmias (associated with both ischemic myocardiopathy and enlargement and dysfunction of the left atrium) and rarely developing gastrointestinal bleeding should be noted associated with angiodysplasia of the right colon. At the same time, the risk of infective endocarditis of calcified valves is reduced in comparison with isolated aortic stenoses of rheumatic etiology.

On examination, it is rare to find anything specific for degenerative stenosis in elderly patients. Unlike young patients, who often have a “slow and small” pulse, even with severe stenosis, due to a decrease in the elasticity of the arteries, the pulse can remain normal. By palpation, a long ascending apical impulse is determined in the 5th intercostal space somewhat outward from the midclavicular line; Systolic tremor may often be palpable. During auscultation, the first tone may not change, but due to functional-hemodynamic changes, it is often observed

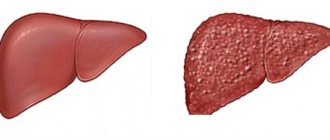

| Figure 4 |

weakening

In this case, the second tone, as a rule, changes, which is especially clearly recorded during long-term observation of the patient: while valve calcification has not led to stenosis, the second tone is intensified (at the same time, at the Botkin point, after the first sound, a systolic ejection tone is sometimes heard), then from -due to reduced mobility of the valves, it is weakened. Aortic stenosis is characterized by a rough fusiform systolic murmur, heard maximally at the left edge of the sternum and carried to the carotid arteries. With senile lesions, this noise has some pathogenetic features (Fig. 4). As can be seen from the diagram, a rheumatic calcified defect creates a hemodynamic “jet” effect during systolic expulsion, giving rise to only auscultatory phenomena, and an isolated calcified stenosis creates a “spray” effect with slightly different hemodynamics and nuances of the auscultated picture [15]. Thus, with severe petrification, Gallawarden's symptom occurs: high-frequency components of the noise are conducted into the axillary region, simulating the noise of mitral regurgitation. In the diagnosis, the clinician will be helped by routine instrumental techniques: ECG (signs of hypertrophy and impaired blood supply to the left ventricular myocardium, arrhythmias), radiography (calcification of the aortic valve, changes in the configuration of the heart, signs of congestion in the lungs) and, of course, EchoCG (the nature of changes in the valve leaflets, accurate assessment of the degree of stenosis and hypertrophy of the myocardium, measurement of intracardiac hemodynamics, impaired local contractility, ejection fraction, pressure gradient between the aorta and left ventricle).

Laboratory indicators, as a rule, are unspecific and reflect extracardiac pathology.

- Treatment tactics

The prognosis for isolated degenerative aortic stenosis is determined by the degree of narrowing of the aortic valve opening (see table), but in general, as a rule, is favorable. This is determined by long-term compensation with an asymptomatic course and slow progression due to the absence of commissural adhesions, as in rheumatic disease. It should be remembered that when symptoms appear, mortality and the risk of complications increases sharply, and 15-20% of patients die suddenly.

In Russia, this nosology as such has not been studied, which means that the practicing physician is not focused on the appropriate diagnostic search. At the same time, the rather rare diagnosis of “atherosclerotic aortic stenosis” due to a lack of understanding of the true nature of the defect leads to the fact that the patient is more often prescribed a diet and cholesterol-lowering drugs rather than referred for a consultation with a cardiac surgeon. But such “pathogenetic treatment” only leads to the progression of petrified stenosis. Conservative symptomatic tactics are generally ineffective in patients with aortic stenosis, and even more so in patients with calcified aortic stenosis. Vasodilating and inotropic therapy requires great caution, and the use of nitrates and diuretics should be avoided.

Rate of progression of aortic stenosis

|

| * Published according to the manual “Cardiology in tables and diagrams”, M. - Praktika, 1996, p. 343 |

In other words, refusal to interpret senile calcified stenosis of the aortic mouth as “atherosclerotic” will lead Russian cardiologists and therapists to form a completely definite view of the treatment prospects for such patients. The only effective treatment worldwide is surgical treatment, either by aortic valve replacement (the method with the best long-term survival rates) or by balloon valvuloplasty. The second method has a number of significant disadvantages: a high risk of complications and the likelihood of re-obstruction, high intraoperative mortality (>6%) and mortality within a year (25%). Meanwhile, this intervention option remains the main one for elderly patients abroad; and in general, degenerative calcification became the main reason for surgical treatment for isolated aortic stenosis (51% of cases of percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty, while calcification of the bicuspid valve and post-rheumatic lesion - 40 and 8% of cases, respectively). Moreover, the age of the operated patients often exceeds 80 years [16].

When writing the last paragraph, the author, of course, was aware that it was impossible to project a foreign situation onto Russian reality. The frequent somatic “negligence” of our patients and the cost of cardiac surgery in the near future do not allow us to hope for any fundamental changes in this issue. This article has only raised a gerontological problem, which has not been discussed in our country for many years. And the point is not so much that 1999 has been declared “the year of the elderly” - domestic doctors must have up-to-date information and abandon outdated formulations and non-existent diagnoses.

Literature

1. Burakovsky V.I., Bockeria L.A. Cardiovascular surgery. M.: Medicine, 1989. 2. Goldstein JA Aortic stenosis // Essentials of Cardiovascular Medicine / Ed. M.Freed and C.Grines. Birmingham, 1994. 3. Monckeberg, JG Der normale histologische Bau und die Sklerose Aortenklappen // Virchows Archiv fur pathologische Anatomie und Physiology und fur Klinische Medizin, (1904). 176, 472. 4. Walter A.V. Chronic aortic valve defects. L., VMMA, 1948, p. 23-88. 5. Ham AW, Cormack DH Histology / JB Lippincott Company, NY 1979. 6. Shestakov V. N. Aortic stenosis. Internal illnesses. Ed. B.I. Shulutko. St. Petersburg, 1994, p. 66. 7. Edwards JE Calcific aortic stenosis / Circulation, 1962, 26, 817. 8. Bierman EL Atherosclerosis and other forms of arteriosclerosis // Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. Hill Book Company, 1987, p. 235. 9. Friedberg CK, Sohval AR Non-rheumatic calcific aortic stenosis // Am. Heart J. 1939 vol. 17 p.m. 452. 10. Karsner HT, Koletsky S. Calcific Disease of the Aortic Valve. J. P. Lippincott, Philadelphia. 1947. 11. Hultgren HN Calcific disease of the aortic valve // Arch. Path., 1948, vol. 45, p. 694. 12. Poller DN, Curry A. et al. Bacterial calcification in infective endocarditis // Postgrad. Med. J., 1989, vol. 65. No. 767, p. 665. 13. Fernandez AL, Montero JA Osseous Metaplasia and Hematopoietic Bone Marrow in a Calcified Aortic Valve // Tex. Heart Inst. J., 1997, 24/3, p. 232. 14. Braunwald E. Valvular heart disease / Heart Disease. Ed. by E. Braunwald - WB Saunders Company, 1988, p. 1023. 15. Roberts WC, Perloff JK Severe Valvular Aortic Stenosis in Patients Over 65 Years of Age // Am. J. Card., 1971, vol. 27, p. 497-506. 16. Logeais Y., Leguerrier A., Rioux C. et al. // International Symposium on Surgery for Heart Valve Disease. Londres, 1989.

Diagnosis of coronary artery stenosis

To determine the extent of damage, the doctor sends the patient for a diagnostic examination:

- blood chemistry;

- blood test for cholesterol and glucose levels;

- load tests (treadmill test, bicycle ergometry);

- stress echocardiography;

- electrocardiography;

- 24-hour Holter monitoring;

- ultrasound examination of the heart and blood vessels;

- coronary angiography;

- computer or magnetic resonance imaging of the chest area.

Stenoses in oncology

Malignant tumors often block the lumen of hollow organs, disrupting their functions. In this case, the patient’s condition always worsens significantly, and the prognosis becomes more serious. If radical surgery for a malignant neoplasm is not possible, then the doctor performs palliative surgery to eliminate stenosis, restore organ function, and improve the patient’s condition.

The patient's condition improves when the tumor begins to disintegrate - it no longer blocks the lumen of the organ. The tumor disintegrates under the influence of chemotherapy, less often on its own. Substances that are released into the blood during massive decay of tumor cells poison the body and can lead to serious complications.

Treatment of coronary artery stenosis

The doctor selects the method of therapy depending on the degree of development of pathological changes, the cause of stenosis, the presence of concomitant diseases, the age and general health of the patient.

Conservative treatment includes:

- drug therapy (the doctor selects medications individually);

- diet therapy;

- lifestyle changes (giving up bad habits, moderate physical activity).

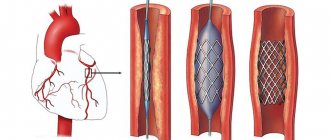

In severe cases, surgery is indicated. Typically, stenting is performed (the vessel is expanded with a balloon and secured with a stent) or bypass surgery (a bypass is created for blood flow).

Primary appointment (examination, consultation) with a cardiovascular surgeon

1850 rub.

Sign up

Treatment of atherosclerosis of heart vessels

Treatment of atherosclerosis of the heart vessels depends on the stage of the pathology, concomitant chronic or third-party diseases, and the age of the patient. Therapy can involve both medication and surgery.

The cardiology center of the Federal Scientific and Clinical Center of the Federal Medical and Biological Agency has a department where patients are under the constant supervision of doctors. Prescriptions are made by the attending cardiologist and constantly monitors the dynamics of treatment. Additionally, instrumental studies of the heart can be performed to adjust treatment or more accurately predict the course of the disease.

If optimal drug therapy is not enough, the cardiologist may suggest surgery:

- coronary angioplasty - insertion of a guidewire with a deflated balloon into a blocked vessel through a catheter. When the desired location is reached, the balloon inflates and compresses all deposits against the walls of the vessel;

- Coronary artery bypass surgery - creating a bypass of the affected vessel using shunts - part of the vein of the leg or the radial artery;

The cardiology center of the Federal Scientific and Clinical Center of the Federal Medical and Biological Agency employs specialists with many years of experience. When you contact, the doctor will determine whether surgery is needed or whether medication can be used.