In 1996, cardiac disease was responsible for more deaths than cerebrovascular disease, lung cancer, breast cancer, and AIDS combined [1]. Acute coronary syndrome includes a spectrum of heart attacks, from unstable angina to myocardial infarction. Non-Q wave myocardial infarction is characterized by coronary symptoms, elevated cardiac enzymes, and ischemic changes detected by electrocardiography (ECG) without the development of Q waves (Table 1).

Compared with myocardial infarctions with Q waves, myocardial infarction without Q waves is not as extensive and does not cause death in the hospital as often, but it is more likely to cause myocardial instability, which leads to an increased incidence of recurrent infarctions and recurrent angina.

The incidence of non-Q wave myocardial infarction has increased over the past 10 years, now accounting for 50% of all acute myocardial infarctions. And some recent studies show that >71% of acute myocardial infarctions are non-Q wave infarctions [2]. Explanations for this increase include earlier detection of heart attacks by measuring levels of specific cardiac enzymes; accelerated treatments, including thrombolytic therapy and percutaneous intraluminal coronary angioplasty; In addition, public awareness of early warning signs has increased.

Mechanisms and distribution of damage

Acute heart attacks range from minor plaque damage and lability of subsequent thrombosis to severe plaque rupture and massive fixed thrombotic masses [3]. Eccentrically located plaques, as well as plaques with a massive lipid core covered with a fibrous layer of varying thickness, are most susceptible to rupture. These plaques become unstable and rupture when exposed to external forces, including normal stress, arterial spasm, platelet aggregation, and the activity of hemostatic proteins. When the plaque ruptures, hemorrhage occurs into the vessel wall, and red blood cells enter the lipid depot. In response to this, a thrombotic reaction occurs in the lumen of the vessel.

Several indicators help distinguish non-Q-wave infarction from Q-wave infarction and unstable angina: characteristics of thrombus formation, time to thrombus resolution, and the presence or absence of collateral vessels. These factors influence the extent of necrosis, the volume of residually unstable myocardium, and the limitation of left ventricular function. Compared with Q-wave infarcts, non-Q-wave infarcts typically have a smaller area, a lower peak creatine kinase concentration, a greater number of functioning arteries in the infarcted area, and larger areas of viable but potentially unstable myocardium in the infarcted area. Compared with unstable angina, infarction without Q waves shows more pronounced arterial occlusion, which leads to decreased blood flow and myocardial necrosis.

Clinical picture

The presentation is consistent with non-Q wave infarction, when there is a combination of persistent chest pain, autonomic symptoms, and ST segment depression [4]. Symptoms resemble other coronary syndromes and range from chest or epigastric discomfort to severe chest pain. Likewise, associated symptoms are the same as those associated with Q-wave infarction, namely nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath, general restlessness, and syncope episodes. Patients with or without a flattened Q wave have a relatively small infarct area with less myocardial necrosis, hence a lower incidence of hypotension and severe left ventricular failure [5]. But with a heart attack with Q waves, the incidence of congestive heart failure and cardiogenic shock is higher already when the patient seeks help.

Signs of a heart attack

The main symptom of myocardial infarction is severe burning, pressing pain behind the sternum. It can spread to the left or right half of the chest, to the neck, to the arm, to the lower jaw, under the shoulder blade (there are different options). The pain syndrome persists for a long time and is not relieved by nitroglycerin.

Other symptoms that may occur:

- pallor;

- cold clammy sweat;

- dyspnea;

- fear of death;

- decreased blood pressure;

Less commonly, pain during myocardial infarction may occur in other areas:

- in the upper abdomen, with hiccups, bloating, nausea, vomiting - abdominal form;

- in the arm, shoulder, lower jaw;

- myocardial infarction can manifest itself as dizziness, disturbances of consciousness - cerebral form;

In addition to the above symptoms, sometimes myocardial infarction is manifested by increasing shortness of breath and resembles an attack of bronchial asthma. In addition, people with diabetes sometimes experience a painless form of myocardial infarction.

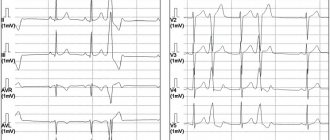

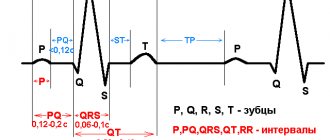

ECG data

Patients in the early phases of a Q-wave infarction typically experience elevated T waves or ST-segment elevations that develop into prominent Q waves within a few hours to a few days. Patients presenting with non-Q wave infarction often have nonspecific ECG changes, including ST-segment elevation and T wave inversion [5]. It should be noted that some patients admitted with transmural infarction do not have ST interval elevation, in addition, sometimes in patients with an initial suspicion of infarction without Q waves, these waves then nevertheless appear - sometimes 3 days after admission. Therefore, before classifying a heart attack as a non-Q wave infarction, you should ensure that you have an ECG that is at least 3 days old.

Non-Q wave infarction is associated with less necrosis, lower creatine kinase concentrations, more potentially active arteries, and a larger volume of unstable myocardium than Q-wave infarction.

Forecast

The prognosis of patients after acute myocardial infarction depends largely on the size of the infarction, the functioning of the left ventricle and the presence or absence of ventricular arrhythmias [6]. A retrospective analysis of 1869 patients admitted for treatment for acute myocardial infarction [6] showed that patients without Q waves had greater pain (both in-hospital and during follow-up) than patients with Q waves during infarction. . In addition, patients with non-Q wave infarction had much poorer survival at 1 year, although their in-hospital mortality was slightly lower than that of other patients.

Subgroup analyzes in the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Study II (TIMI II) [7] included an assessment of prognosis after thrombolytic therapy. ECG changes, features of lesions detected on angiography, left ventricular function, and mortality in patients with infarctions were assessed, and results were compared between patients with and without Q waves. Differences between the 2 groups before treatment included a different ECG pattern and more severe symptoms of angina in the week before the infarction if there is no Q wave during the infarction. In the non-Q wave group, ST segments returned to normal at a higher rate after thrombolytic therapy, indicating for successful reperfusion of arteries affected by infarction. However, angiography revealed no significant differences between the two groups in the number of collateral vessels and the number of patients with a degree of stenosis greater than 60%. In case of a heart attack without a Q wave, in a larger number of patients, the degree of preservation of blood flow in the artery affected by the infarction corresponded to TIMI level 3 (this level corresponds to normal). Patients with absent Q waves due to myocardial infarction had more favorable ejection fractions on non-invasive examination before discharge, and they had significantly more ejection fractions exceeding 55%. As for the clinical picture, infarction without Q waves was associated with fewer cases of congestive heart failure that developed during hospitalization. The 1-year survival rates and recurrent infarction rates were similar in both groups, although there was a trend towards an increased number of recurrent infarctions in the group with non-Q wave infarctions. Analysis based on the criterion of invasiveness/non-invasiveness of treatment measures did not reveal a significant difference in clinical outcomes.

Myocardial infarction

Classification of myocardial infarction

- According to the anatomy of the lesion:

- transmural;

- intramural;

- subendocardial;

- subepicardial.

- By volume of damage:

- large-focal (transmural), Q-infarction;

- small-focal, non-Q-infarction.

- By localization:

- left ventricular myocardial infarction (anterior, lateral, inferior, posterior);

- isolated myocardial infarction of the apex of the heart;

- myocardial infarction of the interventricular septum (septal);

- right ventricular myocardial infarction;

- combined localizations: posteroinferior, anterolateral, etc.

Clinical classification of myocardial infarction

- spontaneous MI (type 1) associated with ischemia due to a primary coronary event, such as plaque erosion and/or destruction, cracking, or dissection;

- secondary myocardial infarction (type 2), associated with ischemia caused by an increase in oxygen deficiency or supply, for example, with coronary spasm, coronary embolism, anemia, arrhythmia, hyper- or hypotension;

- sudden coronary death (type 3), including cardiac arrest, often with symptoms of presumed myocardial ischemia with expected new ST elevation and new left bundle branch block, detection of fresh coronary artery thrombus at angiography and/or autopsy, death occurring before obtaining blood samples or before increasing marker concentrations.

- PCI-associated MI (type 4a);

- MI associated with stent thrombosis (type 4b), which is confirmed by angiography or autopsy;

- CABG-associated MI (type 5).

Clinical picture of myocardial infarction

The most common and characteristic symptom of myocardial infarction is pain. In typical cases, the pain is diffuse and localized in the left side of the chest, behind the sternum. Sometimes the pain is represented by a feeling of heaviness, burning, pressure. Most often, the pain lasts more than 30 minutes, is not relieved by taking nitroglycerin and painkillers, and is accompanied by cold sweat and fear of death. Often the pain occurs in waves, for a long time, then weakening, then intensifying again.

Atypical forms of myocardial infarction

In some cases, the symptoms of myocardial infarction may be atypical. The following forms of MI are distinguished:

- abdominal form - pain is localized in the upper abdomen, accompanied by bloating, nausea, vomiting;

- asthmatic form - represented by increasing shortness of breath, reminiscent of an attack of bronchial asthma;

- atypical pain syndrome may be localized not in the chest, but in the right arm, shoulder, iliac fossa;

- Painless myocardial ischemia is rare, more often in patients with diabetes mellitus. In this case, sometimes patients may experience hypotension, weakness, cyanosis of the lips;

- the cerebral form is represented by dizziness, disturbances of consciousness, and neurological symptoms;

- In some cases, in patients with osteochondrosis of the thoracic spine, the main pain syndrome during MI is accompanied by girdle pain in the chest, characteristic of intercostal neuralgia, which intensifies with changes in body position and palpation.

All complications of myocardial infarction are life-threatening:

- cardiogenic shock;

- heartbreak;

- rhythm and conduction disturbances (ventricular fibrillation);

- acute heart failure;

- development of left ventricular aneurysm;

- development of Dressler's syndrome;

- development of chronic heart failure.

Treatment of myocardial infarction

The only method of treating myocardial infarction, which in a significant proportion of cases allows us to completely prevent negative consequences and preserve the viability of the heart muscle, is the restoration of coronary blood flow in the first hours after the onset of the disease.

The patient requires urgent hospitalization in a hospital capable of immediate coronary angiography, balloon angioplasty and stenting of the coronary arteries. Restoring blood flow through the coronary arteries is possible through thrombolytic therapy (the first 6-12 hours of myocardial infarction), however, this method is less effective and has its limitations.

Prevention of myocardial infarction

Prevention of myocardial infarction means a system of measures, the main focus of which is the prevention of atherosclerosis and, if possible, the elimination of risk factors for myocardial infarction. The goal of prevention after a myocardial infarction is to prevent death, the development of recurrent myocardial infarction and chronic heart failure.

Primary prevention of myocardial infarction is based on maintaining a “healthy lifestyle”, following medical recommendations to prevent the development of coronary artery disease (maintaining normal levels of blood pressure, glucose, cholesterol). The patient must follow proper nutrition, regular physical activity, and give up bad habits.

Secondary prevention after myocardial infarction is necessary to prevent death, the development of recurrent myocardial infarction and chronic heart failure. Long-term prognosis after MI is determined by the severity and extent of stenotic atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries; the degree of left ventricular dysfunction, the age of the patient, the presence of potentially dangerous arrhythmias.

After an MI, constant medical monitoring is necessary to prevent the development of long-term complications of myocardial infarction (chronic heart failure, arrhythmias). These complications are in most cases successfully prevented with the appropriate doctor-recommended regimen, nutrition and special drug treatment. It is recommended to regularly visit a cardiologist (at least once every 6 months) to monitor your general condition and assess the degree of effectiveness of the therapy.

Emergency treatment

As always with acute coronary syndrome, the patient is connected to a continuous cardiac monitor and additionally given oxygen, aspirin, nitroglycerin and antithrombotic therapy. ST-segment elevation in combination with appropriate clinical management should be considered an indication for reperfusion with either thrombolytic therapy or immediate angioplasty, with the choice between these two options made as soon as possible.

Due to the fact that Q waves can appear only 3 days after the patient’s admission, it is necessary to conduct ECG studies for at least 3 days, and only after that can a conclusion be made about myocardial infarction without a Q wave.

Oxygen. Due to the fact that oxygen has low toxicity and significantly improves the well-being of patients, oxygen therapy has not been studied in controlled randomized trials. Intranasal oxygen delivery is indicated for all patients with an oxygen saturation level of less than 90%. Even if the patient has normal oxygen saturation, the use of O2 may still be indicated due to the fact that even with uncomplicated myocardial infarction there is subclinical hypoxemia.

Aspirin. Aspirin should be given to all patients admitted with suspected myocardial infarction. This recommendation is based primarily on the results of the Second International Heart Attack Survival Study [8], in which patients were randomized to different treatment groups: combination treatment with aspirin, streptokinase, with both of these drugs, or without them. The use of 160 mg of aspirin (meaning a daily dose - Translator's note) led to a 21% reduction in death from heart attack compared with placebo. When using aspirin, patients should be carefully monitored for possible gastrointestinal complications.

Nitrates. In a prospective, randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled study [9], nitroglycerin was shown to be effective in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction. Judatt and Warnicka randomized 310 consecutive patients with acute myocardial infarction admitted to their clinic to receive nitroglycerin or placebo. The volume of the infarction, determined by the level of creatine phosphokinase, was 27% less in patients receiving nitroglycerin, the expansion of the infarction was observed 2 times less often, and long-term follow-up (after 29–68 months, on average 43 months) showed that their mortality rate is significantly lower than in the placebo group.

Antithrombotic drugs. The use of heparin in non-Q wave infarction was based on extrapolation of its properties in other coronary syndromes. In a meta-analysis of heparin use for unstable angina [10], heparin reduced the risk of subsequent myocardial infarction and the risk of death by 33%. A direct comparison of low molecular weight heparin and standard unfractionated intravenous heparin showed that enoxaparin sodium (Lovenox) was no worse, and apparently much better, than standard heparin in its ability to reduce the risk of post-infarction ischemic events [11]. Thus, low molecular weight heparin is gaining widespread acceptance as an equivalent alternative to unfractionated heparin.

Treatment

The symptoms that accompany myocardial infarction are very diverse. If myocardial infarction is suspected

The most reasonable action would be to immediately consult a doctor, rather than self-diagnosis or self-medication. In case of myocardial infarction, treatment should begin as early as possible; you must immediately call an ambulance team. Before the team arrives, it is recommended to take a sitting position, preferably on a chair with a backrest, or reclining. Tight, disturbing clothes are unbuttoned and the tie is loosened. It is necessary to immediately take nitroglycerin under the tongue. If the pain decreases within 5 minutes, repeat the dose. It is advisable to chew 300 mg of aspirin. It is important to chew the tablet, otherwise the aspirin will not work quickly enough. In case of cardiac arrest, cardiopulmonary resuscitation is started immediately. Its use greatly increases the patient's chances of survival. Patients with suspected myocardial infarction must be taken to the clinic. After confirmation of the diagnosis, treatment continues in the intensive care unit. You should not hesitate to call an ambulance, since the patient must be hospitalized in a hospital no later than 6 hours from the onset of a painful attack in order to avoid irreversible changes in the myocardium and possible early complications. If possible, a patient with myocardial infarction should be hospitalized in a hospital, where an urgent coronary angiography will be performed, as well as balloon angioplasty (opening of the vessel) and stenting (implantation of a metal frame) of the affected artery, that is, a set of measures that directly affects the cause of the vascular accident.

Scheme of inpatient drug treatment of myocardial infarction:

- Administration of strong painkillers. As a rule, narcotic drugs are used.

- Administration of drugs that reduce blood clotting and promote the resorption of blood clots.

- Intravenous administration of nitroglycerin.

- Intravenous administration of drugs that reduce myocardial oxygen demand.

- Lowers blood pressure and reduces the load on the heart.

- Oxygenation (supply of humidified oxygen).

- Continuous ECG monitoring and blood test control.

The multidisciplinary CELT clinic has created conditions for the most effective treatment of myocardial infarction and its consequences; there is everything necessary to combat this condition and possible complications.

Make an appointment through the application or by calling +7 +7 We work every day:

- Monday—Friday: 8.00—20.00

- Saturday: 8.00–18.00

- Sunday is a day off

The nearest metro and MCC stations to the clinic:

- Highway of Enthusiasts or Perovo

- Partisan

- Enthusiast Highway

Driving directions

Post-infarction treatment

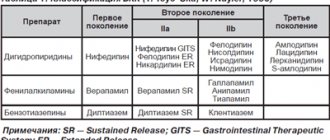

Post-infarction treatment includes the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors), calcium channel blockers and beta blockers.

ACE inhibitors. The use of ACE inhibitors in acute myocardial infarction has been well studied, but there have been no randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of their use specifically in non-Q wave infarction. Most studies included either patients with large anterior wall myocardial infarctions or patients with reduced ejection fraction [12, 13]. Current thinking suggests that ACE inhibitors should be administered immediately after myocardial infarction, especially in patients at risk for congestive heart failure (i.e., those with anterior wall infarction or ejection fraction <40%).

Calcium channel inhibitors. There is no data on the effectiveness of calcium channel blockers in patients with left ventricular failure and infarction with a Q wave. However, in patients with infarction without a Q wave or in lower localizations of infarction without left ventricular dysfunction, calcium channel blockers may reduce the risk of recurrent infarctions. In 1986, a group of researchers studied the extent to which diltiazem hydrochloride could prevent recurrent heart attacks [14]. Their study included 576 patients who were randomized to receive either 90 mg diltiazem every 6 hours orally or placebo for 14 days. When analyzing the treatment results, it was important that in the placebo group the incidence of recurrent infarction and post-infarction angina was significantly higher. Thus, in patients with uncomplicated non-Q wave infarction, diltiazem is effective in preventing post-infarction angina and recurrent infarction. Such results, however, have not been demonstrated for other calcium channel blockers.

Beta blockers. Although beta blockers are widely accepted to be beneficial in non-Q wave infarction, they have not been shown to be of benefit in non-Q wave infarction. At least 3 separate studies [15–17] have assessed the effect of beta blockers in acute non-Q wave infarction, and their results are contradictory. Based on limited and conflicting data on the use of beta-blockers in non-Q-wave myocardial infarction, the American College of Cardiology has classified beta-blockers as having a Class IIb feasibility level (relatively little evidence/opinion support for usefulness/efficacy) for patients with non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. Contraindications to the use of these substances include severe left ventricular failure, severe obstructive pulmonary disease, bradycardia and hypotension.

Beta blockers are useful in the treatment of Q-wave infarction, but their benefit in non-Q-wave infarction has not been proven.

The VANQWISH (Veterans Affairs Non-Q-Wave Infarction Strategies in Hospital) study shows that in the absence of induced ischemia, routine use of coronary angiography is not recommended.

Complications of myocardial infarction

In the first hours of acute myocardial infarction, there is a high risk of developing life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias, including cardiac arrest. During an attack, heart failure may develop - the inability of the heart to adequately cope with its pumping function. This is one of the most severe complications of a heart attack, which can lead to the death of the patient.

Over the next few days following a myocardial infarction, the following may develop:

- various types of arrhythmias;

- shock is a life-threatening condition characterized by a sharp drop in blood pressure, which leads to disruption of the blood supply to all organs and tissues;

- heart failure;

- cardiac aneurysm - a protrusion in the area of the site of myocardial death, complicating the work of the heart;

- the formation of blood clots, which can then break off and travel with the bloodstream to different organs, blocking the blood flow in small vessels;

- dysfunction of the stomach and intestines, gastritis, ulcers.

Diagnostics

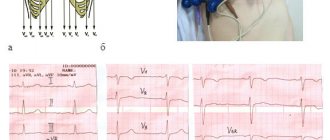

Diagnosis of myocardial infarction is carried out on the basis of data obtained during an examination by a doctor, as well as instrumental studies:

- ECG is the main method for quickly diagnosing myocardial infarction. According to ECG data, it is possible to determine the type and duration of the infarction, the size and location of the lesion.

- Blood chemistry. During and after an attack, specific enzymes and breakdown products of heart muscle tissue appear in the blood;

- Echocardiography is an ultrasound examination of the heart that allows you to identify areas of reduced myocardial contractility and determine the ability of the heart to pump blood.

- Coronary angiography is the injection of a special solution (contrast agent) into the coronary arteries, which blocks x-rays. Coronary angiography is the most accurate and reliable way to diagnose coronary heart disease (CHD), allowing you to determine the nature, location and degree of narrowing or blockage of the coronary artery. This method is the “gold standard” in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease and allows you to decide on the choice and volume of treatment from the first hours of the development of myocardial infarction.

In the multidisciplinary CELT clinic, diagnostics and monitoring of treatment effectiveness are carried out using modern equipment.

Risk assessment

Determining risk in the period following non-Q wave myocardial infarction aims to identify patients at increased risk who are candidates for revascularization. In an era where much attention is paid to cost of care, the risk of subsequent ischemic attacks in stable patients after myocardial infarction must be determined using noninvasive techniques that detect residual ischemia. Techniques for assessing risk and selecting post-infarction interventions include low-stress and presymptomatic tests, stress echocardiography, isotope techniques, and cardiac catheterization. If the patient's initial ECG findings make it difficult to interpret the stress ECG, or if the patient is unable to perform diagnostic exercises, then isotope or echocardiographic studies should be performed using appropriate drugs, depending on the experience and capabilities of the clinic. Invasive testing should be limited to patients with spontaneous ischemia, persistent hemodynamic instability, or evidence of inducible ischemia on noninvasive tests.

Types of myocardial infarction

Based on anatomical location, myocardial infarctions are classified as anterior, lateral, inferior, posterior, apical and septal myocardial infarctions, as well as various combinations thereof.

Based on the volume of damage, heart attacks are currently divided depending on changes in the electrocardiogram (ECG):

- Q-forming infarction - in which significant changes appear on the ECG (pathological Q wave), and significant myocardial damage is observed, such an infarction is also called large-focal or transmural, i.e. penetrating through the entire thickness of the heart muscle.

- Q-non-forming infarction, when the lesion is usually smaller in size than in large-focal myocardial infarction.

Invasive or conservative therapy?

The TIMI IIIB study program [18] included 1473 patients with acute myocardial infarction who were treated with thrombolytics or anticoagulants, and were randomized to receive either conservative treatment (angiography used only when previous medical therapy had failed) or invasive treatment (early use). angiography). Of the total number of percutaneous intraluminal angioplasties, 96.1% were successful. After 6 weeks. These groups were similar in rates of death, myocardial infarction, and exercise performance before symptom onset, measures of primary importance. However, additional indicators characterizing the outcome of treatment, namely: length of hospitalization and readmission rate, were significantly lower in the group receiving invasive therapy.

The only randomized trial comparing early invasive versus early conservative strategies in patients presenting with non-Q wave infarction was the VANQWISH trial [19]. The invasive approach involved catheterization followed by a choice between medical therapy and revascularization, a choice left to the physician. The conservative approach included medical treatment, radioisotope testing to assess left ventricular function, and a predischarge inducible ischemia test (either a treadmill exercise test or a dipyridamole-thallium scan) to determine the need for revascularization. The results of treatment of primary importance (frequency of deaths, myocardial infarction) in the group with conservative treatment were better both at the time of discharge and after 1 month. and 1 year. In this group, mortality rates from any causes were lower at all stages of follow-up over time. Such data seem to indicate that stable patients after non-Q-wave myocardial infarction do not benefit from routine early use of invasive techniques that increase mortality and disability during the first year after myocardial infarction. This study suggests that in the absence of induced ischemia, routine use of coronary angiography followed by revascularization is not recommended.

Classification of myocardial infarction

Author of the material

Today, an expanded classification of myocardial infarction helps to clearly determine the prognosis of the disease and its stage, which allows us to determine the correct treatment tactics.

So, according to the volume of the lesion they distinguish:

- small focal infarction – necrosis forms on a small area of the myocardium;

- large-focal infarction - necrosis affects several walls of the heart muscle.

Taking into account the depth of the lesion, there are the following types of myocardial infarction:

- subepicardial – necrosis is located closer to the outer surface of the myocardium;

- subendocardial – necrosis is located closer to the inner lining of the heart;

- intramural – the focus is located inside the heart;

- transmural - necrosis affects the inner and outer membranes of the myocardium.

Myocardial infarctions are classified according to ECG changes:

- non-Q infarction without ST segment elevation;

- Q-infarction with ST segment elevation.

Based on the location of the necrosis focus, the following are distinguished:

- basal;

- apical;

- septal;

- right ventricular;

- left ventricular.

According to the frequency and timing of development, heart attacks are:

- primary;

- recurrent – develop within 2 months at the site of the primary;

- continued - also develop over 2 months, but in a different place;

- repeated - occur 2 months after the initial infarction and can affect any part of the myocardium.

And finally, the stages of development of a heart attack are determined:

- acute – onset of myocardial damage before 6 hours;

- acute – a necrotic focus forms within 6 hours – 7 days;

- subacute – a period of stabilization of the size of necrosis, characterized by the disappearance of the area of ischemic myocardial damage;

- cicatricial – develops from 7 to 28 days;

- scar - formed 28 days after the onset of a heart attack.

Many cardiac surgeons consider it incorrect to classify myocardial infarction into small- and large-focal ones. According to the WHO classification, myocardial infarction is considered to be only large-focal necrosis of the heart muscle.

When carrying out complex treatment, three main classifications of myocardial infarction are taken into account. First of all, the depth of myocardial damage is taken into account, which is determined on the basis of data obtained from an electrocardiographic study. It is also important to determine myocardial infarction by location and clinical course.

The main activities of the center for endovascular surgery, as well as other popular materials: UAE technique for the treatment of uterine fibroids Technique for embolization of prostatic arteries for adenoma Embolization for prostate adenoma