Treatment of chronic heart failure

M.Yu.SITNIKOVA

, MD, Professor,

T.A.LELYAVINA

, Federal Center for Heart, Blood and Endocrinology named after. V.A. Almazova, St. Petersburg

The main goals of treatment for patients with heart failure (HF) are to relieve symptoms and prevent hospitalization and premature death [1, 2]. The basic principles of drug therapy for heart failure are the earliest possible initiation of treatment after the development of myocardial dysfunction and its lifelong continuation.

The main objectives of the treatment of chronic heart failure (CHF): elimination of symptoms of the disease - shortness of breath, palpitations, increased fatigue, fluid retention in the body; protection against damage to target organs (heart, kidneys, brain, blood vessels, skeletal muscles); improving the patient's quality of life; reduction in the number of hospitalizations; improved prognosis (life extension) [2]. The implementation of these tasks is largely ensured by prescribing medications that help reduce pre- and afterload on the myocardium by influencing the neurohormonal mechanisms of the pathogenesis of CHF; normalization of water-salt balance; increased myocardial contractility.

Appeared in clinical practice in the mid-1970s. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) have become a major advance in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. A number of studies have shown [3-5] the effectiveness of ACE inhibitors in reducing neurohormonal activation.

By inhibiting angiotensin-converting enzyme and reducing the formation of angiotensin (AT) II, these drugs antagonize the renin-angiotensin system. The hemodynamic effects of ACEIs are due to vasodilation with a subsequent decrease in blood pressure (BP).

The vasodilating, diuretic and natriuretic effects of ACE inhibitors increase due to the blockade of bradykinin destruction. The administration of drugs in this group helps prevent the development of left ventricular hypertrophy and myocardial fibrosis or even causes their inversion [3-5].

The effects of ACE inhibitors begin to appear after 3–4 weeks of treatment: dilatation of arterioles develops, total peripheral vascular resistance and blood pressure decrease, renal function improves, diuresis increases, and blood flow in working muscles increases. ACE inhibitors have been shown to improve functional class in patients with heart failure by increasing exercise capacity and reducing clinical symptoms such as shortness of breath, weakness and edema [3–5]. The positive properties of using these drugs is the possibility of reducing the dose of diuretics and prolonging the action of cardiac glycosides.

The basic principles of drug therapy for heart failure are the earliest possible start of treatment from the moment of development of myocardial dysfunction and its lifelong continuation

The use of ACE inhibitors after myocardial infarction significantly reduces the severity of myocardial remodeling. The use of ACE inhibitors is effective in patients with any stage of CHF, including asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure with preserved systolic heart function. But the earlier treatment is started, the greater the chance of prolonging the life of a patient with CHF. Table 1 presents medications in this group recommended for the treatment of patients with CHF [2].

The use of ACE inhibitors after myocardial infarction significantly reduces the severity of myocardial remodeling. Contraindications to ACE inhibitors include current symptomatic hypotension, severe aortic valve stenosis, and bilateral renal artery stenosis.

Contraindications to the use of ACE inhibitors include current symptomatic hypotension, severe aortic valve stenosis, and bilateral renal artery stenosis. ACE inhibitor therapy begins with low doses (Table 1) and is gradually increased to a dose whose effectiveness has been proven in clinical trials. After each dose increase, it is necessary to evaluate the patient's blood pressure, as well as the levels of potassium and creatinine in the blood. The presence of initial manifestations of renal dysfunction in a patient is not a contraindication for prescribing ACE inhibitors, but requires more frequent monitoring of biochemical blood test parameters. Approximately 15% of patients receiving treatment with ACE inhibitors develop a dry cough and, if it causes concern (the number of such cases does not exceed 3%), it is recommended to replace ACE inhibitors with angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARAs). If angioedema develops, ACE inhibitors should be discontinued or the ACEI should be replaced with an ARA.

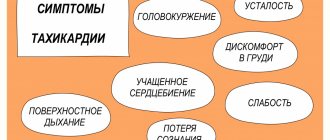

Until recently, beta-blockers were contraindicated in patients with CHF, as it was believed that they reduce myocardial contractility. However, studies in recent years have shown that therapy with beta-blockers promotes a moderate decrease of 3-4% in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) only in the first 10-14 days of treatment [6, 7]. The mechanisms of action of beta-blockers are to reduce heart rate (HR), block cardiac remodeling processes and improve diastolic function of the left ventricle, reduce electrical instability of the myocardium; reducing myocardial hypoxia and restoring the sensitivity of beta-adrenergic receptors [6, 7].

Against the background of long-term therapy with beta-blockers, for example, carvedilol (acridilol), their unique hemodynamic effect manifests itself - an increase in the pumping function of the heart with a decrease in heart rate. The placebo-controlled studies MERIT-HF and CIBIS-II [5] showed that the administration of modified-release metoprolol hemisuccinate and bisoprolol while taking ACE inhibitors and diuretics contributed to a reduction in overall and cardiovascular mortality.

The results of these studies allow us to recommend beta blockers for the treatment of CHF: acridilol - 3.125 mg twice a day, bisoprolol - 1.25 mg once a day, metoprolol succinate CR|XL - 12.5 mg once a day, nebivolol - 1.25 mg per day (Table 2). In the absence of severe hypotension or bradycardia, fluid retention, or worsening symptoms of CHF, it is recommended to double the dosage of drugs every 2-4 weeks. The effects of beta-blockers appear 2-3 months after the start of treatment. It should be remembered that beta-blockers are prescribed only against the background of mandatory use of ACE inhibitors. Beta-blockers recommended for the treatment of patients with CHF are presented in Table 2 [2]. The choice of a specific drug is largely determined by concomitant pathology. Thus, in COPD, nebivolol is safer to use [20], and in the presence of intermittent claudication, carvedilol is safer.

Beta-blockers for chronic heart failure are prescribed only against the background of mandatory use of ACE inhibitors

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists block the binding of angiotensin II (AII) to a specific receptor. The fact that AII is synthesized in some organs and tissues not only with the participation of ACE, but also with the help of other enzymes (the chymase pathway ensures the formation of 80% of AII in the myocardium) justifies the need to use drugs that suppress the activity of AII, regardless of the route of its synthesis. Such drugs are angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARAs). By acting on specific receptors (AT1), the main potentially negative effects of angiotensin II occur, which include vasoconstriction, stimulation of aldosterone synthesis and secretion, sodium and fluid retention, increased circulating blood volume, release of catecholamines from the adrenal medulla, increased myocardial fibrosis, smooth muscle proliferation and endothelial cells, fibroblasts of the vascular wall, etc. ARAs do not inhibit kininase II and the breakdown of bradykinin, therefore they extremely rarely (in no more than 1% of patients) cause cough or angioedema.

Many researchers have shown that long-term use of ARA helps reduce left ventricular hypertrophy and improve myocardial diastolic function [8–10]. Prescribing a combination of an ARA with a diuretic, for example the drug Lozap, as the only RAAS blocking agent in addition to digoxin, promotes the development of the same positive effects as ACE inhibitors, and can replace this group of drugs in patients who experience cough or angioedema while using ACE inhibitors. swelling [9-10]. Taking ARBs at clinically effective doses may cause adverse effects such as hypotension, renal dysfunction, and hyperkalemia as frequently as taking ACE inhibitors. As with ACEIs, it is recommended to gradually achieve target doses of ARBs, the benefits of which have been confirmed by clinical trials. ARBs recommended for the treatment of patients with CHF are presented in Table 3.

It has been shown that long-term use of ARA helps reduce left ventricular hypertrophy and improve myocardial diastolic function

Aldosterone antagonists block the unwanted effects of aldosterone described earlier and act as potassium-sparing diuretics. Taking the aldosterone antagonist spironolactone helps reduce the severity of symptoms of CHF, reduce the number of hospitalizations and improve survival when added to ACE inhibitors (and diuretics and digoxin) in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and class III–IV HF [11]. Therapy with eplerenone, another aldosterone antagonist, reduces mortality and morbidity when added to both ACE inhibitors and beta blockers in patients with reduced LVEF and diabetes after myocardial infarction. Therefore, the use of an aldosterone antagonist should be considered in patients with New York Heart Association class III-IV heart failure in addition to diuretics, ACE inhibitors (or ARBs) and beta-blockers.

Treatment with an aldosterone antagonist should be started with a low dose (Table 4) with careful monitoring of serum potassium and creatinine levels. Hyperkalemia is the most dangerous adverse effect of aldosterone antagonist therapy (as is the case with ACE inhibitors and ARBs). Aldosterone antagonists are not recommended for use in patients with impaired renal function, particularly those with serum creatinine >221 mmol/L (>2.5 mg/dL) and serum potassium >5 mmol/L. Spironolactone may have antiandrogenic effects, particularly causing painful gynecomastia in men. In such patients, eplerenone is a reasonable replacement for spironolactone because it does not block androgen receptors [12]. Aldosterone antagonists recommended for the treatment of patients with CHF are presented in Table 4.

Treatment with an aldosterone antagonist should be initiated at a low dose with careful monitoring of serum potassium and creatinine levels.

The most important group of drugs in the treatment of CHF are diuretics, and their rational combination and dosing flexibility are the key to successful treatment of patients with severe heart failure. There are two main types of diuretics - saluretics and aquaretics. Saluretics reduce the reabsorption of sodium and other electrolytes in the nephron tubules, which increases the excretion of these substances in the urine, and water is excreted along with the electrolytes. Aquaretics reduce the permeability of the tubules to water, reducing its reabsorption and increasing the excretion of free water and, along with it, electrolytes. Although diuretics have not been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in large studies, they are indicated in almost all patients with symptomatic heart failure to relieve dyspnea and signs of sodium and water retention [13, 14].

Most modern diuretics (with the exception of ethacrynic acid) are sulfonamide derivatives. The difference in the action of diuretics primarily depends on the localization of their action in the nephron. For example, acetazolamide acts in the area of the proximal tubules and inhibits the action of the enzyme carbonic anhydrase. In metabolic alkalosis, the effect of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors is enhanced and is accompanied by activation of sodium-hydrogen ion exchange, blockade of sodium reabsorption and diuresis. In other cases (in the absence of alkalosis), the diuretic effect of diacarb is very weak.

Thiazide diuretics (hydrochlorothiazide, indapamide) act on the cortical segment of the loop of Henle and the area of the distal tubules, blocking the activity of the sodium-chloride transporter. They have a moderate effect on sodium reabsorption and, therefore, diuresis, which is observed with normal renal function (with creatinine clearance greater than 30 ml/min).

The most powerful are loop diuretics (furosemide, ethacrynic acid, bumetanide), which block the activity of a special sodium transporter in tubular cells throughout the ascending segment of the loop of Henle. These drugs have a strong diuretic effect, which persists even with reduced renal function (with a creatinine clearance of at least 5 ml/min).

If a patient with heart failure once requires a diuretic, then the use of this group of drugs is usually necessary throughout life, although the dose and type of drug may vary. The basic principle of diuretic treatment is to prescribe the minimum dose of diuretic necessary to maintain a non-edematous state (“dry weight”).

Excessive use of diuretics can lead to electrolyte imbalance (hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypochloremia and hypomagnesemia), hyperuricemia (with risk of gout) and decreased circulating fluid volume (with risk of orthostatic hypotension). When using diuretics, it is recommended to follow several rules: prescribe diuretics in minimal doses in combination with ACE inhibitors; do not strive for forced diuresis; Do not immediately prescribe strong drugs.

When using diuretics, it is recommended to prescribe them in minimal doses in combination with ACE inhibitors; do not strive for forced diuresis; do not immediately prescribe strong drugs

In the presence of edema, diuresis should not exceed the amount of fluid consumed by more than 800 ml. It is considered advisable to use daily selected diuretics to maintain stable diuresis and the patient’s body weight. “Shock” doses of diuretics, used once every few days, are difficult to tolerate by patients and are not recommended. For refractory edema caused by progression of CHF, as well as decreased renal function, hypotension, dysproteinemia, and electrolyte imbalance, a combination of high doses of furosemide administered intravenously (up to 1000 mg/day), a thiazide diuretic and spironolactone (up to 200 mg/day) is advisable.

In cases of severe decompensation of heart failure, when active therapy with diuretics is carried out, and the patient is still bedridden, it is advisable to use unfractionated or fractionated heparins (for example, fraxiparin). This measure helps prevent the development of pulmonary embolism.

Cardiac glycosides have been used in the treatment of CHF since 1785, but recently unknown properties of these drugs have been discovered. When digoxin is used in small doses (0.25 mg/day) in patients with sinus rhythm, it mainly has a neuromodulatory effect, reducing the activity of the sympathoadrenal system (SAS) [15], while the inotropic effect is manifested when only large doses are prescribed. For atrial fibrillation, digoxin is the drug of choice, since by slowing down atrioventricular conduction a significant reduction in heart rate is achieved. This is accompanied by a decrease in myocardial oxygen demand, despite the positive inotropic effect. The higher the initial rhythm frequency, the more pronounced the positive effect of glycosides. For patients with sinus rhythm, digoxin is prescribed in small doses (up to 0.25 mg/day).

The concentration of digoxin in the blood plasma increases gradually, reaching a maximum by the 8th day of treatment, therefore, after 1 week of digoxin therapy, it is advisable not only to evaluate the ECG, but also to conduct Holter monitoring. This approach ensures safe continuation of therapy with cardiac glycosides, since it allows not to miss the appearance of ventricular arrhythmias and atrioventricular conduction disorders. Considering the impossibility of assessing the concentration of digoxin in the blood, we consider it advisable to use this drug 5 days a week (SWR schedule - “except Saturday and Sunday”).

Conclusion

The effectiveness of treatment of patients with CHF with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ARAs, beta-adrenergic receptor blockers, and aldosterone antagonists has been proven by the results of large randomized studies [3-12]. However, in real practice, ACE inhibitors are prescribed to only 30–70% of patients with CHF [16], target doses of ACE inhibitors are 10–20% [17], and aldosterone antagonists are prescribed to 5–20% [18]. When prescribing beta-blockers, the emphasis, unfortunately, is on atenolol and propranolol: doctors recommend them to more than 95% of patients, and for example, carvedilol, which has been widely studied for CHF, is rarely used [19]. To increase the effectiveness of drug therapy for patients with CHF, it is necessary to develop new approaches to organizing long-term observation and treatment in accordance with international and Russian standards.

Literature

1. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of Acute and Chronic heart failure. // EHJ.—2008. - V. 10 (1093). - P. 309. 2. Mareev V.Yu., Ageev F.T., Arutyunov G.P. and others. National recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of CHF (second revision). // Journal Heart Failure. - 2007. - T. 8. No. 2. - pp. 1-35. 3. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. The CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. // N Engl J Med. – 1987. – V. 316 (23). – P. 1429-55. 4. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. The SOLVD Investigators // N. Engl. J. Med. – 1991. – V. 325. – P. 293–302. 5. Flather MD, Yusuf S., K?ber L., et al. Long-term ACE-inhibitor therapy in patients with heart failure or left-ventricular dysfunction: a systematic overview of data from individual patients. ACE-Inhibitor Myocardial Infarction Collaborative Group. // Lancet. - 2000. - V. 355. - P. 1575–81. 6. Packer M, Bristow MR, Cohn JN, et al. The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. // N. Engl. J. Med. – 1996. – V. 334 (21). – P. 1349-55. 7. CIBIS II Investigators and Committees. The cardiac insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II. // Lancet. – 1999. – V. 353(9146). – P. 9-13. 8. Granger CB, McMurray JJ, Yusuf S, et al. CHARM Investigators and Committees. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trial // Lancet.- 2003. – V. 362. – P. 772–6. 9. Maggioni AP, Anand I., Gottlieb SO, et al. Val-HeFT Investigators (Valsartan Heart Failure Trial). Effects of valsartan on morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure not receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. // J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. - 2002. – V. 40. – V. 1414–21. 10. Cohn JN, Tognoni G.; Valsartan Heart Failure Trial Investigators. A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. // N. Engl. J. Med. - 2001. – V. 345. – V. 1667–75. 11. Pitt B., Zannard F., Remme W. J., et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patient with severe heart failure. // N. Engl. J. Med. – 1999. – V. 341 (10). – P. 709—717. 12. Pitt B., Remme W., Zannad F., et al. Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study Investigators. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. // N. Engl. J. Med. - 2003. - V. 348. - P. 1309–21. 13. Goebel JA, Van Bakel AB Rational use of diuretics in acute decompensated heart failure. //Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. - 2008. - V. 5. - P.153–62. 14. Faris R., Flather M., Purcell H., et al. Current evidence supporting the role of diuretics in heart failure: a meta analysis of randomized controlled trials. // Int. J. Cardiol. – 2002. – V. 82. P. 149–58. 15. Hood WB, Jr., Dans AL, Guyatt GH, et al. Digitalis for treatment of congestive heart failure in patients in sinus rhythm: a systematic review and meta-analysis. // J. Card. Fail. - 2004. – V. 10. P. 155–64. 16. Krum H., Tonkin AM, Currie R., Djundjek R., Johnston CI Frequency, awareness and pharmacological management of chronic heart failure in Australian general practice. The Cardiac Awareness Survey and Evaluation (CASE) Study. //Med. J. - Aust 2001. - V. 174. - P. 439-444. 17. Rumsfeld JM Heart failure disease management works, but will it succeed? //Eur. Heart J. - 2004. - Vol. 25(18). — P. 1565—1567. 18. Gonseth J. The effectiveness of disease management programs in reducing hospital readmission in older patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published reports. //Eur. Heart J. - 2004. - V. 25 (18). — P. 1570—1595. 19. Cline CM A cost effective management program for heart failure reduced hospitalization. //Heart. – 1998. – V. 80 (9). — P. 442—446.

See Appendix for figures and tables.

XII Congress “Heart Failure” – 2012: Strategy for prescribing diuretics

Diuretics in the context of mandatory therapy

Edema is one of the common symptoms of internal diseases; therapists, cardiologists and nephrologists especially often have to deal with them. As noted by the head of the Department of Internal Diseases of the Perm State Medical Academy, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor N.A. KOZIOLOV, edema occurs due to a violation of one or more factors of Starling’s colloid-osmotic theory, which determine the exchange of water between capillaries and tissues. These factors include:

- Hydrostatic pressure of blood in capillaries and the value of tissue resistance.

- Colloid osmotic pressure of blood plasma and tissue fluid.

- Permeability of the capillary wall.

The pathogenetic mechanisms of edema formation in heart failure include many links.

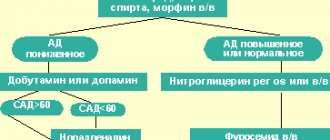

That is why the process of eliminating edema syndrome must be multi-stage. At the first stage, it is necessary to transfer fluid from the extracellular space into the vascular bed. To achieve this goal, drugs of various groups are used: diuretics, neurohormonal modulators (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists) and a number of others. The next step in eliminating edema syndrome is to ensure the delivery of excess fluid to the kidneys and its filtration. For this purpose, drugs that enhance filtration are used - digoxin for atrial fibrillation, dopamine for arterial hypotension and sinus rhythm, aminophylline in patients with systolic blood pressure (SBP) above 100 mm Hg. Art. At the final stage of treatment, reabsorption in the renal tubules is blocked. This ensures the removal of excess fluid from the body. At this stage, diuretics are indispensable. Data on the effect of diuretics on the life prognosis of patients suffering from heart failure are contradictory. However, it can be considered proven that mortality and the number of hospitalizations due to the use of diuretics increase only in cases where patients are not prescribed angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors simultaneously with a diuretic [1].

There is evidence that diuretics may have a beneficial effect on prognosis. Thus, according to a Cochrane meta-analysis, adequate diuretic therapy reduces the relative risk of death by 76% and the progression of chronic heart failure (CHF) by 93% [2]. The effect of diuretic therapy on life prognosis has not yet been clearly established, but the ability of these drugs to improve the clinical condition of patients with edematous syndrome has been identified.

Edema syndrome is widespread in patients with CHF III–IV functional class (FC) according to the classification of the New York Heart Association (NYHA, New York Heart Association). CHF IV FC is often found in older age groups: among people aged 50 to 60 years, the incidence is 28 cases per 1000 people, in the age group 60–70 years – 51 cases. At the age of 90 or more, every 10th person suffers from severe forms of heart failure accompanied by edema.

In Europe, diuretics are widely used to treat patients with CHF; according to various sources, they are used by 70–80% of patients with this diagnosis, while in our country, according to the results of the EPOCHA-2002 study, diuretics are prescribed to only 24% of patients with CHF. As emphasized by Professor N.A. Koziolova, the situation in Russian clinical practice needs to be changed, since peripheral edema is a symptom, reliably (p

The attitude of cardiologists – the authors of American and European recommendations – towards diuretics is indicative. The recommendations issued by the American College of Cardiology, in particular, indicate that “diuretics and salt restriction are indicated in all patients with existing or newly diagnosed symptoms of CHF and a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in the presence of evidence of fluid retention.” The European Society of Cardiology guidelines state that "diuretics can be used as needed to relieve signs and symptoms of fluid retention independent of LVEF, but are not indicated to reduce the risk of hospitalization and death." Indications on the advisability of diuretic therapy can also be found in documents of the American Heart Failure Society and the All-Russian Scientific Society of Cardiology, and recommendations for diuretic therapy have a high level of evidence - Ia. The authors of these documents also emphasize that diuretic therapy should be continuous (with the exception of individual cases when a significant improvement in clinical status and cardiac function has been achieved - then therapy can be interrupted), while prescribing loading doses once every few days can even lead to a worsening of the condition .

According to American and European recommendations, loop diuretics (furosemide, torsemide) should be used for initial diuretic therapy. If it is not possible to achieve the desired effect with a loop diuretic, combination therapy should be resorted to (a potassium-sparing or thiazide diuretic can be added to the loop diuretic). Therapy should be started with the minimum effective doses, keeping in mind that high doses of diuretics increase the risk of overall mortality in patients with CHF.

Several loop diuretics are currently used: furosemide, torsemide, bumetanide and ethacrynic acid. A meta-analysis of studies of these drugs showed that torasemide can lead to a decrease in mortality and the number of hospitalizations compared with furosemide, as well as an improvement in the FC of heart failure in the patient [5]. The GOLD-CHF study compared short-acting loop diuretics with long-acting drugs. In the group of patients receiving a long-acting diuretic, a significantly more pronounced decrease in the levels of atrial and brain natriuretic hormones, as well as a significant decrease in weight, was observed.

When prescribing loop diuretics, attention should be paid to the duration of action of the drug and the recommended starting and maximum doses (Table 2) [6]. The drug with the longest half-life should be selected, such as torsemide. A necessary condition for safe diuretic therapy is dose titration from starting to target. If this rule is observed during the dosage regimen, the patient will receive the minimum effective (and therefore the most safe) dose of the drug, which will allow diuretic therapy to continue without harming the patient’s health.

Patient with chronic heart failure: pleiotropic effect of diuretics. Is it possible to reduce the risk of death?

Head of the Department of Therapy, State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education "Russian National Research Medical University named after. N.I. Pirogov”, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor G.P. ARUTYUNOV touched upon the issue of the evolution of diuretic therapy. The history of the use of diuretics goes back centuries. Paracelsus also tried to use herbal infusions and salts of heavy metals to remove excess fluid from the body of his patients. Later, through observations, it was found that sulfonamide drugs have a diuretic effect. In addition, they are characterized by a weak ability to inhibit carbonic anhydrase.

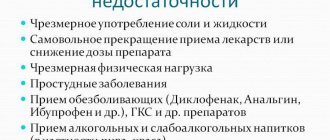

Sulfonamide derivatives began to develop as diuretics in several directions at once: as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, as well as loop and thiazide diuretics. Sulfonamide drugs were discovered in 1949, and this date can be considered the starting point of diuretic therapy in its modern sense. At the same time, many diuretics appeared relatively recently, for example, torasemide was discovered in 1993. All diuretics are characterized by a common basic mechanism of action - they increase the volume of urine excreted, thereby increasing the excretion of sodium cations and anions excreted along with them, primarily Cl-. The volume of extracellular fluid directly depends on the NaCl content in the plasma, which means that it decreases due to the loss of these ions. Diuretic therapy is widely used for CHF, as it reduces the severity of symptoms of the disease and improves the patient’s quality of life. However, the prescription of diuretics to patients with CHF should be carried out in accordance with certain rules:

- Therapy begins only if there are symptoms of circulatory failure.

- The prescription of diuretics should occur during therapy with ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers.

- Diuretic therapy is carried out only on a daily basis. Intermittent courses of diuretic therapy lead to hyperactivation of neurohormonal systems and an increase in the level of neurohormones.

- The prescription of diuretics should be carried out according to the principle “from weakest to strongest.”

- When a clinical effect is achieved (reduction of clinical manifestations of circulatory failure, increase in tolerance to physical activity), titration of the diuretic dose begins “downward”.

The choice of diuretic is based on a special algorithm (Fig. 1). When prescribing therapy for elderly unexamined patients, possible nephrosclerosis should be assumed, and in the presence of CHF, diuretic therapy is required; When choosing initial therapy, preference should be given to loop diuretics. Thiazide diuretics are considered safe only in combination with ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers; among loop diuretics, the safest are drugs with a maximum half-life, since they protect the functioning glomeruli, delaying the onset of the “rebound”, in which sodium returns to the body from the primary urine after the end of action of a loop diuretic. It is also advisable to give preference to drugs that have pleiotropic effects, for example, affecting the deposition of collagen. These drugs include the loop diuretic torasemide, which blocks the C-terminal proteinase of procollagen and thus reduces collagen synthesis.

Of particular interest in the context of duration of action are long-acting, slow-release diuretics (Britomar). Their concentration in the blood plasma changes gradually, without jumps, which leads to an increase in the Tmax interval by 45% (Fig. 2). With the use of torasemide, potassium metabolism disorders also develop significantly less often than with the use of furosemide. Another important pleiotropic effect of torasemide is its ability to minimally affect the rhythm of life of patients: the number of urinations after taking this drug is significantly lower than after taking other diuretics. The latter statement was confirmed in a 9-month study comparing furosemide with torsemide [7]. It was revealed that torasemide has a number of advantages over thiazide diuretics and furosemide (Table 3), which allows the widespread use of torasemide-based drugs in patients suffering from CHF and with signs of circulatory failure.

Long-term therapy with diuretics

The main requirement for long-term diuretic therapy was noted by the head of the consultative and outpatient department of the Research Institute of Cardiology named after. A.L. Myasnikova Federal State Budgetary Institution RKNPK, Doctor of Medical Sciences Ya.A. ORLOV, is safety and only then is portability. The prescription of diuretics in some cases is accompanied by disturbances in carbohydrate metabolism and an increase in uric acid levels, but these disorders are delayed, in contrast to hypokalemia, which develops quite quickly and is one of the most serious complications of diuretic therapy. The effect of hydrochlorothiazide on these parameters was studied in a 9-week study by SM Smith et al. (Fig. 3) [8].

A study examining the safety profile of torasemide demonstrated that long-term administration of the drug at a dosage of 5 mg/day (as well as 10 mg/day) did not have a negative effect on biochemical blood test parameters. Direct comparative studies of hydrochlorothiazide and torsemide also demonstrated the absence of a reliably recorded effect of the latter on potassium and blood glucose levels, while hydrochlorothiazide decreased the concentration of potassium ions and increased glucose levels.

In a comparative study conducted by J. Cosin et al. (2002) [9], patients with CHF with preserved systolic heart function (CHF-SHF) received torasemide and furosemide (9.6 ± 1 and 31 ± 2 mg/day, respectively) for 6 months. At the end of this period, 7% of patients in the furosemide group showed a decrease in K+ levels

However, reducing the dose of a diuretic is possible only if the known cause of decompensation is eliminated; therefore, special attention to the safety of the prescribed drugs should be paid even at the stage of choosing a diuretic. Torsemide is considered one of the diuretics with an optimal safety profile; the minimal effect of this drug on mortality in patients with CHF has been confirmed by large studies (Fig. 4) [9]. It has been proven that torasemide reduces the risk of overall mortality in patients with CHF by almost 2 times compared to furosemide and mortality from cardiovascular diseases by more than 2 times. In addition, while taking torsemide, there is a more pronounced improvement in the clinical condition of patients, which is reflected, in particular, in the results of the 6-minute walk test [11]. Torsemide is also characterized by better tolerability and a longer half-life than thiazide diuretics, which indicates the advisability of its use in patients with CHF who require diuretic therapy. In this case, it is necessary to begin therapy with the minimum effective doses, without increasing them unnecessarily.

Conclusion

Diuretic therapy is an integral part of the complex treatment of patients with CHF. However, as a rule, it is prescribed to patients with high (III–IV) FC CHF, and the duration of taking diuretics is measured in years. All this explains the special requirements for the safety and tolerability of diuretic drugs. Today, it is considered proven that long-acting loop diuretics, such as Britomar, have the optimal combination of safety, tolerability and effectiveness. It is also characterized by a number of pleiotropic effects, such as the ability to block collagen synthesis. The effectiveness and safety of torasemide have been confirmed by a number of large studies in which the drug was compared with both placebo and other diuretics, including loop diuretics. In these studies, torasemide demonstrated the ability to significantly reduce the severity of edema without adversely affecting metabolic processes.