Most abdominal organs are supplied with blood from the celiac trunk, the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries and their branches. This ensures the flow of nutrients and oxygen to the tissues.

The danger of the disease lies in the fact that its symptoms are significantly similar to the clinical picture of many diseases of the digestive tract, which is what makes diagnosis difficult. Exacerbation of the disease can have tragic consequences, so timely diagnosis and treatment are extremely important.

The mechanism of development of the disease is long-term disruption of blood flow and ischemic processes. To varying degrees, this disease occurs in more than half of elderly patients. The acute stage of the disease is intestinal infarction or acute occlusion of abdominal vessels. The pathology is also known as abdominal toad or tonsillitis.

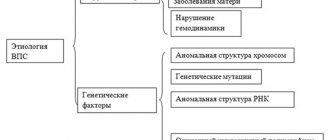

The disease is divided into celiac, superior and inferior mesenteric forms. It depends on the vessel that is involved in the process. Each form has its own characteristic symptoms, which arise depending on the location of the outbreak. Also, abdominal ischemia occurs in several stages. The first stage is compensation, when the disease manifests itself slightly, and the vessels continue to provide blood flow. The subcompensated stage is accompanied by a deterioration in the function of the abdominal vessels, which is manifested by a pronounced clinical picture. Decompensation occurs when the damage to the vessel is so great that it completely disrupts the blood supply to the tissue.

Introduction

Acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) is a life-threatening vascular disease that often requires immediate surgical treatment. Early diagnosis and immediate intervention that restores mesenteric blood flow prevents intestinal necrosis and patient death. The cause of AMI can be different, and the prognosis depends on the depth of pathological changes [1, 2].

The severity of progression depends on the pathogenesis of AMI and the choice of treatment; diagnosing this pathology remains a challenge for the clinician. Early diagnosis and effective treatment are primary for improving clinical outcomes; any delay in diagnosis leads to an increase in mortality to 59-93% [2]. Although mesenteric angiography remains the gold standard for diagnosing mesenteric ischemia, it is not applicable in many situations [3]. Laparoscopy is increasingly used to diagnose various diseases, although its role in the early diagnosis of AMI remains controversial.

External examination of the wall of the small intestine is the only thing that allows us to indirectly judge ischemic changes in the mucous and submucosal layer in the early stages of AMI [4]. However, in some situations, the role of diagnostic laparoscopy (DL) may be discussed as an addition to the clinical examination and choice of treatment for patients with AMI. Critically ill patients are one group where laparoscopy may be particularly valuable. In addition, DL can be performed directly at the bedside of a non-transportable patient [5].

Forecasts

Despite the fact that ischemia is a very serious disease, timely medicine allows us to do everything to ensure the most favorable prognosis.

The sooner an accurate diagnosis is made to the patient and a treatment regimen (medical, surgical) is selected, the higher the likelihood of a successful result.

Even with the most complex brain pathologies, with timely help, it is possible to preserve the maximum number of nerve cells, which means preserving or restoring the functions of the body.

Of great importance is how patient care is provided during the treatment process (especially after surgery). It is important to ensure that the patient has the correct body position, nutritional regimen, and catheter care. Massage helps significantly speed up recovery.

The 5th hospital has an experienced team of specialists: including neurologists, neurosurgeons, surgeons, and cardiologists. The clinical diagnostic laboratory, the RK and MRI department, the department of clinical and functional diagnostics are equipped with high-quality equipment, with the help of which high-precision studies can be quickly carried out. Here you will receive competent assistance for coronary heart and cerebral vascular disease. Treatment and rehabilitation programs are available for both citizens of the Republic of Belarus and foreign citizens. The doctors at Hospital No. 5 have extensive experience treating patients from Moscow and other Russian cities.

Arterial embolism

Arterial embolism is the most common form of AMI, it is observed in 40-50% of cases [6]. Many mesenteric emboli have their source in the heart cavity. Myocardial ischemia or infarction, atrial tachyarrhythmia, endocarditis, cardiomyopathies, ventricular aneurysms, valve diseases - all these conditions are risk factors for the development of mural thrombosis. Many arterial emboli enter the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). While 15% of arterial emboli remain at the ostium of the SMA, 50% penetrate more distally into the middle colic artery, which is the first major branch from the SMA. The onset of symptoms is usually dramatic, as a consequence of insufficient development of collaterals [7]. Often, diagnosis of SMA embolism is possible only intraoperatively, based on visualization of small bowel ischemia. Because most SMA emboli travel distally into the middle colic artery, the anatomy allows the inferior pancreaticoduodenal vessels to provide reperfusion to the proximal jejunum while the remainder of the small bowel is subject to ischemia or infarction.

Possible consequences

The most common are:

- necrosis of the intestinal wall - occurs when there is insufficient compensatory forces, dead tissue undergoes rupture and the contents enter the abdominal cavity, this causes severe peritonitis;

- narrowing of the intestine - let’s assume that as a result of a chronic process, scar tissue appears in small areas as a result of healing; it fuses with other loops of the intestine, with the mesentery.

Scars form a new mechanical obstruction due to narrowing of the intestine

Arterial thrombosis

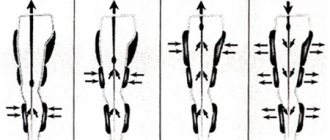

Acute mesenteric thrombosis accounts for 25-30% of all cases of ischemia. Almost all of them are associated with severe atherosclerosis developing at the origins of the SMA. The blood supply to internal organs in this situation is maintained due to the development of collaterals. Ischemia or infarction of the small bowel occurs when the last visceral vessel or important collateral becomes occluded. The extent of ischemia or infarction in this case is greater than with embolism and extends from the duodenum to the transverse colon.

Risk factors

Common provoking factors for the development of intestinal ischemia are:

- diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia syndrome, high blood pressure, smoking, old age, which cause atherosclerosis;

- strong pressure deviations below/above normal;

- cardiac dysfunctions such as arrhythmia, chronic failure;

- drug abuse;

- clotting factor impairment in antiphospholipid syndrome, hereditary hemoglobinopathy.

Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia

Approximately 20% of mesenteric ischemia is non-occlusive. The pathogenesis of nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (NMI) is not entirely understood but is often associated with low cardiac output associated with diffuse mesenteric vasoconstriction. Vasoconstriction of splanchnic organs is a response to hypovolemia with decreased cardiac output and hypotension. As a result of insufficient blood flow, intestinal hypoxia occurs, which inevitably leads to intestinal necrosis. Conditions predisposing to NMI include age over 50 years, myocardial infarction, heart failure, liver and kidney disease, and major abdominal or cardiovascular surgery. However, these patients may not have risk factors. This condition often develops in patients in critical condition with a host of concomitant diseases; NMI often begins unexpectedly and results in high mortality.

Preventive measures

To take good care of your vessels you need to:

- stick to vegetable dishes, cereals in the menu, eat salads and fruits every day;

- limit the consumption of spicy meat products, fatty and fried meat and fish, legumes, smoked meats, canned food;

- stop smoking;

- fight low mobility, walk more, play sports;

- control and prevent chronic diseases.

Timely consultation with a doctor and examination will help prevent severe ischemia. Acute abdominal pain should not be treated independently under the pretext of food poisoning. If they have not occurred for the first time, or there are other consequences of arterial damage (myocardial infarction, stroke), then one should remember about systemic vascular damage and take measures to prevent complications.

Mesenteric venous thrombosis

Mesenteric venous thrombosis (MVT) is the rarest type of mesenteric ischemia, accounting for 10% of AMI [8]. It can develop secondary to any intra-abdominal disease (tumor, peritonitis, pancreatitis), or as a result of a primary blood clotting disorder, and only in 10% of cases MVT is classified as idiopathic. MVT is usually segmental in nature with edema and hemorrhages in the intestinal wall. Thrombi usually arise in the venous arcades and spread further into larger vessels. Hemorrhagic infarction occurs in cases where intramural vessels are blocked. The thrombus can usually be palpated in the superior mesenteric vein. Involvement of the inferior mesenteric vein and colonic vessels is rare. The transition of the unchanged intestinal wall to the ischemic zone with venous thrombosis occurs more smoothly than with arterial embolism or thrombosis.

Complication

Intestinal ischemia is fraught with the formation of strictures (narrowing of intestinal sections). And a number of patients may develop short bowel syndrome, which results in fear of eating.

The most serious risk with renal ischemia is complete occlusion of blood vessels and blockage of blood vessels. The main danger is the cessation of excretion of waste products from the body. The result is complete kidney failure, which can be fatal.

Serious consequences and complications are possible if coronary brain disease is not taken under medical control in a timely manner. Damage to brain tissue is fraught with limitation of motor activity (up to paralysis), loss of mental abilities, loss of legal capacity and disability.

Comprehensive rehabilitation helps to effectively reduce the risk of complications. For example, a special program “Rehabilitation after ischemic stroke” is available at hospital No. 5. The two-week course includes consultations, a comprehensive examination, individual exercise therapy, physiotherapy, drug therapy, massage, and acupuncture.

Diagnosis

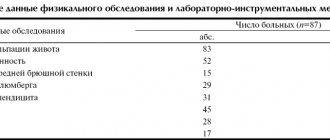

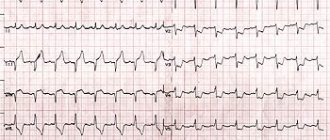

Many signs and symptoms associated with AMI also occur with other intra-abdominal pathologies, such as pancreatitis, acute diverticulitis, acute intestinal obstruction, and acute cholecystitis. In general, patients with SMA embolism or thrombosis have an acute onset of the disease, rapid development of symptoms, and rapid deterioration of the condition, while with MVT and NMI the clinical picture develops more smoothly. With SMA embolism, the increase in symptoms occurs at lightning speed due to the lack of collateral blood supply and manifests itself in the form of severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Dehydration, impaired consciousness, tachycardia, tachypnea and circulatory collapse are rapidly increasing. Laboratory data show metabolic acidosis, leukocytosis, blood concentration.

AMI can rapidly progress to intestinal infarction; timely diagnosis and treatment are of strategic importance [1, 9]. A high level of suspicion based on history and initial examination data serves as the cornerstone in the diagnosis of acute intestinal ischemia. When diagnosis is made on the first day, survival rate is 50%, and when it is delayed it drops to 30% or lower. Laboratory studies often show hemoconcentration, leukocytosis, and metabolic acidosis. High levels of amylase, aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, and creatinine phosphokinase are often found in test results, but they are not sensitive or specific for diagnosis. Hyperphosphatemia and hyperkalemia occur later and often accompany intestinal infarction.

Radiation examination of the abdominal cavity is also nonspecific. In the initial stage of the disease, 25% of patients may have normal radiological data. Characteristic radiographic changes, such as thickening or compaction of the intestinal wall, are less common than in 40% of patients. Air in the portal vein is a late symptom and is associated with a poor prognosis. At a high level of suspicion for AMI, CT is more likely to clarify specific details. Some authors report a sensitivity of 93.3% and a specificity of 95.9% for CT scans with IV contrast [3, 9].

Thickening of the intestinal wall, intramural hematoma, dilated and fluid-filled intestinal loops, congestion of the mesenteric vessels, pneumatosis, gas in the mesenteric and portal veins, infarction of other organs, arterial and venous thrombosis may be visible on CT scanning. The value of the study increases in the absence of indications for immediate laparotomy for suspected AMI. Early angiography increases the chances of survival.

Mesenteric angiography allows the differentiation of embolism and thrombotic arterial occlusion. An embolus most often occludes the middle colic artery, the first major branch of the SMA. Thrombotic disease most often affects the source of the SMA, and the vessel is not visualized at all. MVT is characterized by a generalized slowing of arterial blood flow. Usually the lesion is segmental in nature, in contrast to NMI, when normal venous outflow is preserved [3, 9].

Laparoscopy: an alternative diagnostic procedure

Although CT is recognized as a radiological test with high sensitivity, it is limited in many situations [10]. Patients with mesenteric ischemia often suffer from chronic venous insufficiency and heart disease, which preclude the use of IV contrast. In addition, severe dehydration and acidosis are often present in these patients, requiring prolonged correction and delaying treatment. Such a pause is highly likely to lead to irreversible changes in the intestines. Laparoscopy can be an alternative to other traditional methods. In addition, unstable patients require constant intensive care, and laparoscopy can be performed directly at the patient's bedside, which is extremely important for early diagnosis.

Limitations of laparoscopy in the early diagnosis of AMI

Emergency laparoscopy can be used to diagnose and treat some forms of acute abdomen. DL is also indicated in clinically unclear situations and for staging the oncological process.

Data on the effectiveness of DL for mesenteric ischemia are contradictory [4, 10, 11]. Limitations are associated with questionable intraoperative data in the early stages of ischemia. It is well known that at the beginning of the development of AMI, primary changes occur in the inner layers of the intestinal wall (mucosal and submucosal layer). Laparoscopy performed at this stage may not detect changes, since the serous surface is often intact. The inability to palpate the mesentery to assess pulsation is another disadvantage of laparoscopy in diagnosing AMI [4, 10-13].

However, other important signs of intestinal ischemia such as edema, hyperemia, focal hemorrhages, dark effusion or visible gangrene can be detected during laparoscopic examination of the intestine. Experimental studies performed in pigs have opened up additional possibilities for laparoscopy in terms of interpreting intraoperative data in the early stages of mesenteric ischemia. The study describes the use of ultraviolet light and the drug fluorescein to identify AMI. This substance makes it possible to identify fluorescent viable tissue from the dark ischemic intestinal wall [14, 15]. Another factor limiting the use of laparoscopy is the effect of pneumoperitoneum on mesenteric blood flow. High intra-abdominal pressure may reduce venous return with a subsequent fall in cardiac output. High intra-abdominal pressure can also have a direct effect on the aorta and its branches. Therefore, intra-abdominal pressure should not exceed 10-15 mmHg [12]. All this ensures the safety of the DL.

Symptoms

Depending on the nature of the course, the symptom complex manifests itself in different ways. For example, the acute form appears suddenly, develops quickly and is characterized by pronounced symptoms. The chronic form is characterized by gradual development. The first sign of ischemia is a sharp, sharp pain located in the umbilical region and the upper right quadrant of the abdomen. If the back wall suffers from a lack of oxygen, this provokes violent peristalsis and a false urge to defecate. Early stages are characterized by the presence of:

- severe nausea;

- profuse vomiting;

- severe diarrhea with blood in the stool.

In acute manifestations, an infarction of the intestinal mucosa immediately occurs, then other symptoms develop. Already in the first hour the following clinical picture appears:

- wave-like, severe pain attacks after eating, lasting up to 2 hours, which go away on their own and reappear after a meal (feelings similar to appendicitis);

- sudden loss of body weight;

- refusal to eat;

- dyspeptic disorders;

- rise in temperature;

- disappearance of peristalsis.

At the same time, signs of severe intoxication of the body and peritonitis may develop.

Treatment

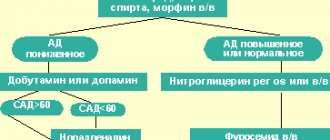

Once a diagnosis of AMI is made, treatment should begin immediately. With the exception of NMI, which requires drug therapy, most cases of AMI dictate the need for surgical intervention to restore intestinal blood flow.

The presence of symptoms of peritoneal irritation is more likely to indicate intestinal infarction than ischemia and requires immediate laparotomy. Even in the absence of intestinal necrosis, surgery is usually necessary to exclude irreversible changes in the intestinal wall. Resection of ischemic bowel is the most common surgical procedure for AMI. Satisfactory arterial pulsation, good blood supply to the remaining segment and the absence of peritonitis dictate the indications for primary anastomosis.

Intra-abdominal contamination, questionable blood supply to the preserved segment of the intestine and poor general condition of the patient are contraindications to the imposition of an interintestinal anastomosis. In this situation, removing both ends of the intestine is the safest procedure. In a small number of patients with the occlusive form of AMI, in the presence of reversible changes, an attempt at revascularization is possible. Embolectomy, thrombectomy, endarterectomy, or bypass may prevent bowel resection in the early stages of AMI. Massive extended gangrene of the intestine is not subject to surgical treatment, since it does not lead to an improvement in the patient’s condition [3, 9].

The role and place of laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is a quick and easy procedure. The speed of execution of DL is one of its advantages, which should not be underestimated when a decision needs to be made immediately. In patients in serious condition, laparoscopy is effective and safe [3]. Acute abdomen due to acidosis may occur in some cases; DL helps in differential diagnosis. It is convenient to perform it at the bedside of a seriously ill patient requiring intensive hemodynamic and respiratory treatment. The advantages of the method are the absence of the need to transport a seriously ill patient, quick diagnosis, elimination of auxiliary tests and low cost.

Jaramillo et al. [5] conducted a retrospective study in the intensive care unit of the Texas Institute of Endosurgery, which showed the feasibility and safety of performing laparoscopy at the patient's bedside over a period of 13 years. The study included 13 patients with an average age of 75.5 years. All of them were on mechanical ventilation under sedation. DL was easily performed under local anesthesia and IV sedation. Pneumoperitoneum was created with a Veress needle followed by an intra-abdominal pressure of 8-10 mmHg. The average duration of the procedure is 35 minutes. 46% of them had mesenteric necrosis, and all of them died within 48 hours without any additional procedures. Another 30% of patients had negative DL, 1 had fecal peritonitis and died within 24 hours. The remaining 15% were found to have acute acalculous cholecystitis.

Another potential area for the use of laparoscopy to diagnose AMI is in intensive care unit patients. Abdominal complications are a serious problem in the early postoperative period in patients undergoing major cardiac surgery using extracorporeal circulation. In this case, the mortality rate reaches 70%. Early diagnosis and timely treatment are an important factor determining the outcome. However, clinical examination of the abdomen is difficult in these patients [5].

A study conducted at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, showed the accuracy of laparoscopy in identifying abdominal complications in patients after cardiac surgery. DL was performed in 17 patients. No pathology was found in one. In 6 out of 17, ischemia of the right half of the colon was detected; in 5 out of 17, massive expansion of the colon without ischemia was detected, which was confirmed by laparotomy. 3 developed acute cholecystitis, confirmed by transection. In one case, fibrinous peritonitis without a primary focus was discovered during DL, which was confirmed by laparotomy. And only in one case was DL false-negative; laparotomy revealed pancreatic necrosis [16].

Second-Look

In 1921, Cokkins [17], who described AMI, stated that the diagnosis of this disease was impossible, the prognosis was hopeless, and treatment was pointless. Despite progress in diagnosis, surgical and non-surgical treatment, and intensive care, mortality in AMI remains high. Most researchers report a mortality rate of 59–93% [4, 11]. The lack of pathognomonic symptoms and their late recognition limit therapeutic measures to, at best, bowel resection. But even after this, ischemia of the remaining intestine can progress. In mesenteric venous thrombosis, after resection of a necrotic loop and administration of anticoagulant therapy, thrombosis can progress further from the ischemic segment [13].

In 1965, Shaw [18] proposed second-look laparotomy to overcome difficulties in assessing the adequacy of bowel resection. Originally recommended for assessing the condition of anastomoses, second-look has found widespread use in our time. This is especially important for determining the viability of the remaining intestinal segment after surgery for AMI. However, the timing of second-look is uncertain, especially in patients with intestinal anastomoses. In most cases, anastomotic failure occurred on days 3-5; second-look laparoscopy made it possible to timely identify this complication and prevent peritonitis. Excluding early intra-abdominal complications, the optimal period for performing second-look laparoscopy is 48-72 hours after the first operation [19].

Symptoms

- The following symptoms are characteristic of IHD: shortness of breath (in severe forms - both in motion and in a quiet position, in developing, chronic forms - in motion), rapid heartbeat, disruptions in blood pressure, pain in the chest, pain in the heart.

- Brain pathologies are characterized by deterioration of brain activity, and at the same time, memorization, concentration, the appearance of irritability, problems with sleep (in chronic forms), confusion, loss of vision, impaired sensitivity of the arms and legs, vomiting, nausea (in acute forms) .

- With ischemic intestinal pathologies, pain appears in the navel, upper abdomen, diarrhea, intestinal bleeding, bloating, tachycardia, abdominal tension, drop in blood pressure, diarrhea, vomiting.

- Symptoms of renal ischemia include frequent urge to urinate at night, severe swelling of the face, legs, arms, weakness, fatigue, and the smell of ammonia from the mouth.

- Symptoms of ischemic limb disease are intermittent claudication, a feeling of numbness in the arms and legs, a feeling that the arms and (or legs) are constantly cold, and ulcers on the legs. Patients also often notice that their nails begin to grow more slowly.

Very often (especially in chronic diseases, especially kidney pathologies), the symptoms are very “smeared” for a long time. Without a comprehensive diagnosis, a disease can easily be confused with another. In some patients, the symptoms affect only one organ, while in others the problem is more extensive, and there are problems with the heart, intestines, and kidneys at the same time.

Second-look laparoscopy

This procedure is increasingly replacing open second-look surgery as it reduces surgical and anesthetic trauma. Anadol et al. [22] compared open and laparoscopic second-look in patients with mesenteric ischemia. In the first group (n=41), repeat laparotomy was performed in 23 patients. In the second group (n=36), a 10 mm trocar was left until the laparotomy wound was sutured and a second-look was performed using a laparoscope in 23 patients. 16 laparotomies in the first group (70%) were in vain. Two patients (8%) in the laparoscopic group required repeat resection, whereas 20 (87%) did not require laparotomy. The authors decided that patients with mesenteric ischemia already suffer enough and deserve minimally invasive endoscopic surgery [22].

Second-look laparoscopy is described as a safe method for determining intestinal viability, reducing the risk of complications and allowing a quick determination of treatment tactics. In addition, short and shallow anesthesia minimizes the risk of deterioration in critically ill patients. At the same time, mortality is reduced due to shortening the duration of the operation [5, 19, 20].