Abdominal ischemia (mesenteric thrombosis, acute intestinal ischemia, intestinal circulatory failure) occurs when blood flow through the arteries that supply blood to the intestines slows or stops. This condition has many potential causes, including a clot blocking the artery or narrowing of the artery due to the development of cholesterol plaques. Blockages can also occur in veins, but they are less common.

Regardless of the cause, decreased blood flow to the gastrointestinal tract leaves tissues without sufficient oxygen, causing cell dysfunction and cell death. If the damage to the intestinal wall is severe enough, intestinal gangrene develops, followed by its rupture (perforation), resulting in fecal peritonitis and death.

Saving a person with mesenteric thrombosis is possible only with timely correct diagnosis, followed by removal of the blood clot and assessment of intestinal viability. With conventional symptomatic treatment, mortality reaches 99%, with surgery to remove the intestine - 80%, with timely removal of the blood clot and control of the intestine - 25%.

General information

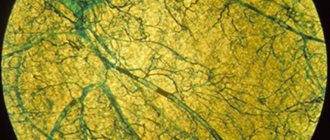

It is based on the formation of a blood clot (thrombus) in the mesenteric vessels, leading to blockage/reduction of their lumen. The blood supply to the small intestine/partially large intestine comes from the superior/inferior mesenteric artery, and the blood supply to the left half of the colon comes from the mesenteric artery. The outflow of blood from the intestines occurs through the superior/inferior mesenteric and splenic veins. The figure below shows the mesenteric vessels (branches of the mesenteric arteries/veins) that provide blood supply/outflow from the small intestine.

Thrombosis within the mesenteric circulation can occur in both arteries and veins (arterial thrombosis/venous thrombosis). Among occlusive lesions, thrombosis of mesenteric arteries accounts for 33.2-50.7%, and thrombosis of veins - 7.9-10.1%.

Mesenteric arterial thrombosis

The superior mesenteric artery is predominantly affected (85-90%), with the thrombus localized in the 1st segment (the mouth of the superior mesenteric artery). The inferior mesenteric artery is affected only in 10-15% of cases. The extent of intestinal damage is determined by the localization of the blood clot in the arteries. Accordingly, with thrombosis of the first segment of the superior mesenteric artery, acute ischemia / necrosis spreads to the entire small intestine, and in 50% of cases to the blind/right half of the colon; when the thrombus in segment II, ischemia / necrosis spreads to the terminal jejunum/ileum. When the thrombus is localized in segment III, only the ileum is affected.

Mesenteric venous thrombosis is caused predominantly by a thrombus of the mesenteric veins and much less often by a thrombus of the portal vein. Highlight:

- primary (ascending) thrombosis, if the intestinal veins are initially thrombosed, and later large venous trunks; with primary thrombosis of the intestinal veins, limited lesions of the small intestine develop (up to 1 m);

- secondary (descending), if damage to the mesenteric veins occurs due to primary occlusion of the splenic/portal veins; it is characterized by the spread of the pathological process to the entire portal system with total necrosis of the small intestine.

Quite often, thrombosis of mesenteric venous vessels is combined with venous thrombosis of another location. Venous thrombosis extremely rarely leads to severe ischemia and venous infarction of the intestine ; they usually develop slowly and are accompanied by inflammation in the intestinal wall. However, against the background of primary arterial ischemia of the intestine, intestinal edema can quickly develop, which significantly complicates venous outflow and contributes to the formation of blood clots in the intestinal veins.

Thrombosis of the mesenteric vessels of the intestine develops, as a rule, against the background of hypercoagulation of the blood and a pronounced slowdown in blood flow, which is caused by damage to the vessel wall ( endarteritis , atherosclerosis , vasculitis ). Ischemic intestinal disease occurs predominantly in middle-aged/elderly people, equally common in men and women. Despite the relatively low incidence (0.9–1.2% of the total number of acute surgical pathologies of the abdominal cavity), acute mesenteric ischemia caused by thrombosis of the mesenteric vessels is accompanied by high mortality (in the range of 55–80%).

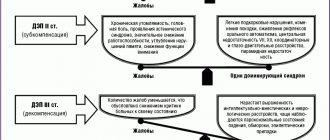

Depending on the location and type of thrombus (in relation to the lumen of the vessel - parietal, occluding, floating), a change in the state of mesenteric blood flow occurs in the form of compensation, subcompensation, slowly/rapidly progressive decompensation. Complete blockage of a vessel by a thrombus leads to a sharp decompensation of blood circulation and the development of ischemia / necrosis over a wide area.

Pathological changes in thrombosis of mesenteric vessels, depending on the severity/compensation of blood circulation, initially lead to the development of ischemia, and in cases of longer-term disturbance of intestinal blood flow, intestinal infarction , necrosis and peritonitis . At the earliest stages of thrombosis, only the mucous membrane is subject to ischemia, and with ischemia lasting more than 3 hours, destructive-necrotic processes develop, involving all layers of the intestinal wall, which leads to ischemic/hemorrhagic intestinal infarction. Damage to the entire intestinal wall contributes to the translocation of the infectious agent (bacteria) from the intestinal lumen into the abdominal cavity and arterial bloodstream, thereby contributing to the development of sepsis / peritonitis . In some cases, the situation is complicated by intestinal perforation as a result of intestinal infarction/necrosis, which causes the rapid development of peritonitis.

It should be remembered that thrombosis of the mesenteric vessels is an emergency condition that requires the fastest possible diagnosis and urgent medical care. With delayed diagnosis and the absence of urgent surgical intervention, acute intestinal ischemia quickly progresses to a state of irreversible necrosis , causing severe metabolic disorders, leading to the development of multiple organ dysfunction and death. Thus, late hospitalization (more than a day from thrombosis) significantly aggravates the condition of patients, and surgical interventions in most cases are ineffective.

Features of the blood supply to the intestines

The intestinal loops are in a “suspended” state and are secured in place by a dense mesenteric ligament. Arterial and venous vessels pass between the leaves. They are located almost parallel. The arteries (superior and inferior mesenteric) arise from the abdominal aorta and divide the blood supply into sections:

- The superior mesenteric artery carries blood to the small intestine, cecum, ascending colon, and most of the transverse colon. It carries out 90% of the blood supply, so the lesions are more widespread and clinically severe.

- The inferior mesenteric artery supplies a much smaller area (30% of the transverse colon, descending, sigmoid, rectum).

Between the main arteries there are “spare” collateral vessels. Their task is to help blood supply to the damaged area. A feature of intestinal collaterals is that they pump blood in only one direction: from the area of the superior artery to the inferior mesenteric. Therefore, in the case of upper-level thrombosis, no help can be expected from anastomoses.

Venous drainage from the intestine goes to the portal vein. Difficulty occurs when it narrows due to liver disease. Collateral circulation is formed by a group of portocaval anastomoses between the portal and vena cava. The small intestine is in the worst position. It does not have a developed collateral network.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of thrombosis has been studied and is well described by Virchow's triad. The main links in thrombus formation are: damage to the vascular endothelium, changes in blood flow and hypercoagulation (violation of the rheological properties of blood), the development of each of which has its own reasons.

The formation of intravital blood clotting in a vessel occurs in several stages and includes platelet agglutination, fibrinogen coagulation, erythrocyte agglutination and precipitation of plasma proteins.

Prevention measures

Thromboembolism prevention is based on timely detection and treatment of heart and vascular diseases, so we recommend undergoing a comprehensive examination at least once a year.

It is also necessary to lead a healthy and active lifestyle, exercising moderately and adhering to the principles of a healthy diet. The diet should be dominated by foods of plant origin, but it is advisable to exclude foods containing cholesterol.

In the summer, you should avoid dehydration by following a drinking regime. Bad habits, such as smoking, increase the risk of blood clots - give them up.

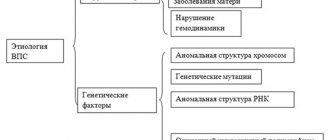

Causes

The immediate causes of a blood clot in the vascular bed of the mesentery are changes in the vascular walls against the background of slow blood flow and increased blood clotting. Indirect causes of the development of a blood clot in the arterial bloodstream of the intestine are: chronic heart failure , hypercoagulable processes , cardiosclerosis , endocarditis , vascular atherosclerosis , pancreatitis , trauma .

The causes of intestinal thrombosis in the venous vessels of the intestine are mechanical (strangulation of the mesentery, adhesions, volvulus), closed abdominal trauma with damage to the mesenteric veins/intestinal contusion, blood diseases (thrombocytosis), hemodynamic disorders, increased intra-abdominal pressure, taking oral contraceptives, portal hypertension , malignant neoplasms, destructive forms of pancreatitis , appendicitis , cholecystitis cardiac decompensation , taking hormonal drugs, Crohn's disease , ulcerative colitis , intra-abdominal infections of the abdominal organs, abscesses .

Laparoscopy: an alternative diagnostic procedure

Although CT is recognized as a radiological test with high sensitivity, it is limited in many situations [10]. Patients with mesenteric ischemia often suffer from chronic venous insufficiency and heart disease, which preclude the use of IV contrast. In addition, severe dehydration and acidosis are often present in these patients, requiring prolonged correction and delaying treatment. Such a pause is highly likely to lead to irreversible changes in the intestines. Laparoscopy can be an alternative to other traditional methods. In addition, unstable patients require constant intensive care, and laparoscopy can be performed directly at the patient's bedside, which is extremely important for early diagnosis.

Symptoms

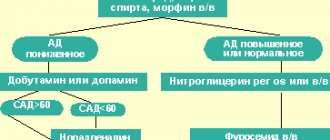

Symptoms of mesenteric intestinal thrombosis vary greatly and are determined by the stage of the disease. Thus, the reversible stage of intestinal ischemia is characterized by hemodynamic/reflex disorders. In most cases, acute circulatory disorders in the mesenteric vessels begin suddenly. With arterial thrombosis, prodromal phenomena can be observed (in 1/3 of patients), the cause of which is the formation of a blood clot/narrowing of the artery due to atherosclerosis , which is manifested by the appearance within 1-2 months of nausea, vomiting, periodic abdominal pain, bloating, and unstable stools.

Venous thrombosis in most cases develops more slowly (over 2-5 days). The stage of ischemia is manifested by an attack of sharp, predominantly constant, uncertainly localized abdominal pain, radiating to various parts of the abdomen. Less commonly, patients may indicate the presence of pain in the umbilical region or epigastrium. Nausea/vomiting appears, many patients experience 1-2 times loose stools, which occurs due to spasm of the intestinal loops, and only in 25% of cases does gas/stool retention occur immediately.

The characteristic behavior of patients is noted. Due to unbearable pain, patients cannot find a place for themselves, scream, ask for help, pull their legs to their stomach and take a knee-elbow position. Upon examination, patients have severe pallor of the skin. With a high localization of the thrombus in the superior mesenteric artery, an increase of 60-80 mm Hg is observed. Art. blood pressure (Blinov's symptom). The tongue is wet, the pulse is slow, the stomach is soft and painless. Leukocytosis in the blood .

In the absence of emergency surgical care, intestinal infarction . At this stage, the symptoms of intestinal thrombosis are complemented by intoxication and local manifestations (peritoneal symptoms) from the abdominal cavity. In the stage of a heart attack, the clinic is somewhat smoothed out: the intensity of the pain syndrome decreases, which contributes to a calmer behavior of patients; mild euphoria , expressed in inappropriate behavior of the patient; The pulse quickens and blood pressure normalizes. Diarrhea may develop , and vomiting . The tongue becomes dry. At this stage, blood may appear in the vomit/stool. Due to the appearance of effusion/bloating, the abdomen increases slightly in volume, but remains soft. The Shchetkin-Blumberg sign and muscle tension in the abdominal muscles are absent.

Unlike the ischemic , when the pain is diffuse in nature/localized in the epigastric region, the infarction stage is characterized by pain in the lower abdominal cavity, which is caused by the affected area of the intestine. In addition, upon palpation of the abdomen, local pain appears, which corresponds to the areas of intestinal infarction. Mondor's symptom is rarely encountered (on palpation of the abdomen, an inflamed intestine is identified as a dense formation without clear boundaries).

Intestinal necrosis and peritonitis develop quite quickly . At this stage, due to increasing intoxication, the patient’s condition sharply worsens, electrolyte imbalance, dehydration, and acidosis . Patients are adynamic, delirium may appear.

The specificity of peritonitis in acute circulatory disorders in the mesenteric vessels is the relatively late appearance of the Shchetkin-Blumberg symptom /muscle tension (compared to purulent peritonitis). Peritonitis begins to develop from below: diarrhea mixed with blood continues, some patients develop intestinal paresis, accompanied by gas/stool retention. The pulse is frequent, thread-like, up to 120-140 beats/minute, the blood pressure level decreases. The color of the skin is ashen-gray, dry tongue, high leukocytosis with a shift to the left. The course of intestinal peritonitis often ends in the death of patients after 2-3 days. Venous infarction is characterized by a longer course: 5-8 days. Much less often, the clinical symptoms are sparse with erased symptoms, which is more common in elderly/senile patients.

Treatment

Once a diagnosis of AMI is made, treatment should begin immediately. With the exception of NMI, which requires drug therapy, most cases of AMI dictate the need for surgical intervention to restore intestinal blood flow.

The presence of symptoms of peritoneal irritation is more likely to indicate intestinal infarction than ischemia and requires immediate laparotomy. Even in the absence of intestinal necrosis, surgery is usually necessary to exclude irreversible changes in the intestinal wall. Resection of ischemic bowel is the most common surgical procedure for AMI. Satisfactory arterial pulsation, good blood supply to the remaining segment and the absence of peritonitis dictate the indications for primary anastomosis.

Intra-abdominal contamination, questionable blood supply to the preserved segment of the intestine and poor general condition of the patient are contraindications to the imposition of an interintestinal anastomosis. In this situation, removing both ends of the intestine is the safest procedure. In a small number of patients with the occlusive form of AMI, in the presence of reversible changes, an attempt at revascularization is possible. Embolectomy, thrombectomy, endarterectomy, or bypass may prevent bowel resection in the early stages of AMI. Massive extended gangrene of the intestine is not subject to surgical treatment, since it does not lead to an improvement in the patient’s condition [3, 9].

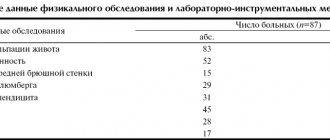

Tests and diagnostics

Diagnosis of the disease should primarily be based on an analysis of clinical manifestations. Patients should be hospitalized at the slightest suspicion of acute disturbance of mesenteric circulation. The diagnosis must be made or completely rejected within the near future, since with long-term observation the condition of patients worsens significantly, and they become inoperable of peritonitis

The main diagnostic methods are angiography and diagnostic laparotomy. Selective angiography allows you to accurately determine the localization of occlusion, the type of blood flow disturbance, the extent of the lesion, and the presence/condition of collateral compensation pathways for blood flow. Angiographic diagnosis of blood flow disorders in mesenteric vessels is based on a comprehensive analysis of the arterial, venous and capillary phases of angiograms.

More complete information can be obtained by performing angiography in combination with laparoscopy. Diagnosis in the stage of ischemia is difficult, since it is necessary to base it on functional signs (lack of peristalsis, spasm of intestinal loops, etc.). Laparoscopic data allow us to accurately judge the extent of intestinal damage/degree of destruction of the intestinal wall. In later stages (infarction and peritonitis), laparoscopic diagnosis is mandatory.

Active differential diagnosis is necessary for diseases that in their manifestations may be similar to the symptoms of acute disorders of mesenteric circulation in the first hours of the disease ( myocardial infarction , pancreatitis , intestinal obstruction , etc.). The clinical picture of an acute abdomen can also be caused by inflamed mesenteric lymph nodes (mesadenitis).

How does the chronic form of thrombosis manifest?

The chronic form of thrombosis should be considered in patients with heart failure complicated by myocardial infarction. The clinic distinguishes 4 stages:

- I - the patient has no complaints, the thrombus is an accidental finding during angiography;

- II - typical complaints of pain along the intestines after eating, the person refuses food because of this;

- III - constant pain, flatulence, impaired absorption of the small intestine, diarrhea;

- IV - the occurrence of intestinal obstruction, which manifests itself as an “acute abdomen”, with peritonitis and gangrene.

Forecast

The prognosis of thrombosis of mesenteric vessels depends on the timeliness of surgical intervention. With delayed diagnosis/lack of urgent surgical intervention acute intestinal ischemia caused by thrombosis of mesenteric vessels progresses to a state of irreversible necrosis , causing severe metabolic disorders, leading to the development of multiple organ dysfunction and death. Surgical interventions after 12-24 hours after thrombosis of intestinal vessels are ineffective (postoperative mortality reaches 85-90%). More favorable results are observed after surgery on intestinal vessels in the first 4-6 hours (up to 75% of those recovered).

Introduction

Acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) is a life-threatening vascular disease that often requires immediate surgical treatment. Early diagnosis and immediate intervention that restores mesenteric blood flow prevents intestinal necrosis and patient death. The cause of AMI can be different, and the prognosis depends on the depth of pathological changes [1, 2].

The severity of progression depends on the pathogenesis of AMI and the choice of treatment; diagnosing this pathology remains a challenge for the clinician. Early diagnosis and effective treatment are primary for improving clinical outcomes; any delay in diagnosis leads to an increase in mortality to 59-93% [2]. Although mesenteric angiography remains the gold standard for diagnosing mesenteric ischemia, it is not applicable in many situations [3]. Laparoscopy is increasingly used to diagnose various diseases, although its role in the early diagnosis of AMI remains controversial.

External examination of the wall of the small intestine is the only thing that allows us to indirectly judge ischemic changes in the mucous and submucosal layer in the early stages of AMI [4]. However, in some situations, the role of diagnostic laparoscopy (DL) may be discussed as an addition to the clinical examination and choice of treatment for patients with AMI. Critically ill patients are one group where laparoscopy may be particularly valuable. In addition, DL can be performed directly at the bedside of a non-transportable patient [5].

List of sources

- Pokrovsky A.V., Yudin V.I. Acute mesenteric obstruction // Clinical angiology: Guide / Ed. A. V. Pokrovsky. T. 2. M.: Medicine, 2004. P. 626-645.

- Savelyev V. S., Spiridonov I. V., Boldin B. V. Acute disorders of mesenteric circulation. Intestinal infarction: Guide to emergency surgery / Ed. B. S. Savelyeva. M.: Triada-X, 2004. pp. 281-302.

- Solomentseva T. A. Acute disorders of mesenteric circulation in a therapeutic clinic // Acute and emergency conditions in medical practice. 2011. No. 2. P. 8-14.

- Yushkevich D.V., Khryshchanovich V.Ya., Ladutko I.M. Diagnosis and treatment of acute disturbance of mesenteric circulation: current state of the problem // Med. magazine 2013. No. 3. P. 38-44.

- Katerina J.M., Kahan S. Emergency Medicine: Trans. from English - M.: MEDpress-inform, 2005. - 336 p.

Second-look laparoscopy

This procedure is increasingly replacing open second-look surgery as it reduces surgical and anesthetic trauma. Anadol et al. [22] compared open and laparoscopic second-look in patients with mesenteric ischemia. In the first group (n=41), repeat laparotomy was performed in 23 patients. In the second group (n=36), a 10 mm trocar was left until the laparotomy wound was sutured and a second-look was performed using a laparoscope in 23 patients. 16 laparotomies in the first group (70%) were in vain. Two patients (8%) in the laparoscopic group required repeat resection, whereas 20 (87%) did not require laparotomy. The authors decided that patients with mesenteric ischemia already suffer enough and deserve minimally invasive endoscopic surgery [22].

Second-look laparoscopy is described as a safe method for determining intestinal viability, reducing the risk of complications and allowing a quick determination of treatment tactics. In addition, short and shallow anesthesia minimizes the risk of deterioration in critically ill patients. At the same time, mortality is reduced due to shortening the duration of the operation [5, 19, 20].