Atrial fibrillation and atrial fibrillation are currently equivalent terms. They have similar causes, clinical manifestations and changes on the electrocardiogram. They can often transform into each other. Atrial fibrillation is understood as a heart rhythm disorder in which the atria and ventricles contract in their own pattern, and not sequentially, so the frequency of contraction of the atria and ventricles is different.

Predisposing factors for the occurrence of atrial fibrillation are: coronary heart disease (CHD), arterial hypertension, heart defects, structural heart diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, excess weight, diabetes mellitus, sleep apnea, chronic kidney disease, thyroid dysfunction.

There are conservative (antiarrhythmic drugs) and surgical methods for treating atrial fibrillation. More details about them in the article “atrial fibrillation”.

Over the past 30 years, several types of surgical treatment have been developed.

— surgical isolation of the left atrium, — “corridor” procedure, — “labyrinth” operation — a method of surgical ablation.

The most effective among them was the “labyrinth” operation, which was first performed in 1987 by cardiac surgeon J. Cox in St. Louis.

Over the years, this operation has undergone three modifications - Maze-1, Maze-2 and Maze-3. Maze -1 was modified because it was associated with sinus node dysfunction and intraatrial conduction delay. Maze-2 was abandoned due to the extreme complexity of the procedure. And in 1992, J. Cox developed a third option (Maze-3), which combined all the advantages of the previous options and was easy to implement. It is worth noting that this operation is combined and is currently the “gold standard” for correcting mitral valve disease in combination with atrial fibrillation. In its pure form, the “labyrinth” (surgical ablation method) is performed extremely rarely due to its high morbidity.

To understand the essence of the “labyrinth” operation, you need to understand the cause of atrial fibrillation.

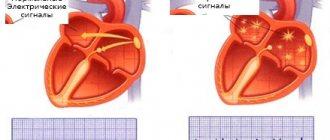

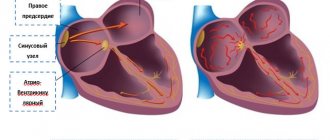

The human heart consists of four chambers, the left and right atrium and the left and right ventricle. Normally, the nerve impulse should go from the sinus node, located in the wall of the right atrium, to the atrioventricular node in the interatrial septum. In this case, the atria and ventricles of the heart contract correctly. With atrial fibrillation, the correct course of the impulse is disrupted. Some of the impulses, as it should be, go to the atrioventricular node, and some return to the sinus node and cause extraordinary contraction of the atria.

The essence of the “labyrinth” operation is to destroy the conduction pathways that are responsible for the occurrence and maintenance of arrhythmia. This is achieved by a surgical “incision and suture” method (blue straight lines in the diagram) through the atria, by excision of the posterior wall of the left atrium along with the pulmonary veins and making multiple small incisions in the right and left atria, forming a so-called “labyrinth”, which does not allows the nerve impulse to return back and cause an extraordinary contraction of the atrium. Simply put, the impulse that wants to return to the sinus node runs into microscopic cuts in the heart and fades away. As a result, the impulse goes where it should normally go, i.e. to the atrioventricular node, which causes the ventricles of the heart to contract and promotes proper contraction of the heart.

Scheme

The “Labyrinth” technique has not found wide clinical application due to the long time of artificial circulation, cross-clamping of the aorta, high risk of bleeding, and lack of experience in performing this technique. Therefore, a number of modifications of this operation have been proposed using various physical methods of ablation of the walls of the atria, replacing the scalpel: radiofrequency, irrigation radiofrequency, ultrasound, cryogenic, laser and microwave exposure.

Contraindications

Contraindications to the labyrinth operation are:

• Sharply increased size of the left atrium. • High value of the cardiothoracic index, with low amplitude of ƒ-waves on the ECG in leads V1. • Pulmonary hypertension. • Kidney and liver failure. • Low left ventricular ejection fraction (less than 30%). • Long-term chronic form of AF in the anamnesis, because in this case, restoration of sinus rhythm after surgery is practically not observed. • General contraindications before cardiac surgery. They depend on the underlying heart disease and are considered by a cardiac surgeon on a case-by-case basis.

Heart surgery

- Coronary artery bypass grafting on a beating heart

- Reconstruction of the left ventricular cavity for cardiac aneurysms

- Operation “labyrinth” for atrial fibrillation

- Complex forms of valve-preserving correction of valvular heart defects

- Angioplasty of the trunk

- Operation Ross

Operation “labyrinth” for atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (the second name is atrial fibrillation, abbreviated as AF) is a heart disease that is increasingly manifesting itself as an independent pathology that affects hearts with normal anatomy. In fact, it is an epidemic involving more and more victims. The professional medical literature paints a very gloomy outlook regarding the spread of AF. It is known that more than 5 million US citizens currently have AF, and that by 2050, the number of Americans with AF is projected to increase to 12 million if the rate of AF continues at current levels.1 Without going into complex and While the reasons for such a rapid spread of this disease are not fully understood, we note that a patient with emerging AF acquires three physiological consequences of AF: 1) increased heart rate, leading to a decrease in the volume of blood ejected by the heart into the aorta per unit of time, and in rare cases leading to rapid development of rapid rhythm-mediated cardiomyopathy; 2) loss of the pumping function of the atria, which also leads to a decrease in the volume of blood ejected by the heart into the aorta per unit of time; 3) stagnation of blood in the non-contracting atria with the risk of blood clots forming in them and their subsequent separation into large vessels.2 The occurrence of AF carries a fivefold increase in the risk of developing embolic stroke.3 Thus, treatment of AF, including surgery, is extremely relevant.

In 1987, experimental studies in St. Louis (USA) under the leadership of James L. Cox led to the appearance in cardiac surgery of the “labyrinth” operation, later named after D. Cox (Cox-Maze operation).4 The meaning of the Cox-Maze operation is in interrupting any possible circuits of the electrical impulse in the atria, preventing the triggering of repeated contraction of the atria due to the same electrical impulse. Thus, the Cox-Maze procedure eliminates the ability of the atrium to flutter or fibrillate.

Figure 1 shows schematically the meaning of the Cox-Maze operation in the author's illustration by Dr. D. Cox.

Figure 1. Note that due to the cuts made in the atria (wide blue lines), all “attempts” of the electrical impulse to return back and again cause contraction of the atrium muscles, causing flutter or atrial fibrillation, end up in a dead end (thin arrows). For these "attempts" exit from the maze is impossible. Only one path of the electrical impulse ends with an exit from the labyrinth - this is the path of normal propagation of the impulse from the sinus node, located in the atrium, to the atrioventricular node, from which contractions of the ventricles of the heart occur (thick arrows). (AVN= atrioventricular node; LAA- left atrial appendage, PVs= pulmonary veins; RAA= right atrial appendage; SAN= sinoatrial node).

Figure 2 shows the lines of the incisions created during the Cox-Maze operation.

Figure 2. From the article “Surgical Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation” by Rochus K. Voeller, Richard B. Schuessler, Ralph J. Damiano, Jr. in Cardiac Surgery in the Adult, edited by Lawrence H. Cohn and L. Henry Edmubds, Jr.

Dr. D. Cox used in practice the most technologically simplest method of making cuts - using a scalpel and scissors. After the incisions are made, the integrity of the atria should be restored using a straight suture along the incision lines. This method of operation is called “cut and sew”, which means “cut and sew”.

The long-term results of the Cox-Maze operation in the “cut and sew” modification are fantastic. At 15 years of follow-up, 94% of operated patients maintained sinus rhythm without taking antiarrhythmic drugs! Below is a slide from a report by Dr. D. Cox, given in December 2012 at the Dallas-Leipzig Valve conference.

Slide 1. The curve characterizing the long-term results of the Cox-Maze operation in the “cut and sew” modification is highlighted in black. Curves of other colors – five-year results of treatment of AF using catheter methods (no comments needed!).5

A feature of the Cox-Maze operation in the “cut and sew” modification is the time required to perform it, which is not always possible during complex cardiac surgery on heart valves or for lesions due to coronary artery disease. In this regard, alternative energy effects on the atrial myocardium have been developed to replace the “cut and sew” technique4. These types of energy are cryo-energy, microwave, radio frequency energy and ultrasound. All of these alternatives significantly reduce the duration of the Cox-Maze operation, but are inferior to “cut and sew” when assessing long-term results. On the other hand, it should be noted that all of the listed options for energetic impact on the atrial myocardium during the Cox-Maze operation, inferior to “cut and sew”, give an incomparably better long-term result in comparison with catheter treatments for atrial fibrillation (see slide 1).

The Heart Surgery Center LLC uses two options for performing the Cox-Maze operation: “cut and sew” and using radiofrequency energy. The choice of the type of effect on the atrial myocardium is made depending on the complexity of other components of the operation and the time required to perform them, as well as on the expected degree of positive physiological impact of the result of cardiac surgical correction on the mechanisms of development of atrial fibrillation. In the case of isolated atrial fibrillation, the Cox-Maze operation is performed exclusively in the author’s “cut and sew” modification.

Slide 2. Dr. James Cox during a talk he gave on December 5, 2012 at the Dallas-Leipzig Valve conference.

LINKS

1 Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee.Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010;121(7):e46–e215.

2 Zachary J. Edgerton and James R. Edgerton. A review of current surgical treatment of patients with atrial fibrillation. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2012;25(3):218–223.

3 Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB, Levy D. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1998;98(10):946–952.

4 Rochus K. Voeller, Richard B. Schuessler, Ralph J. Damiano, Jr. Surgical Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation. In the book "Cardiac Surgery in the Adult", edited by Lawrence H. Cohn and L. Henry Edmubds, Jr.

5 James Cox. The Hybrid Approach for AF: The Best of Both Worlds... Or Not! Dallas-Leipzig Valve, December, 5-7, 2012

Preparing for surgery from the patient's side

Before the operation, the patient must perform a number of examinations in the clinic at his place of residence:

• Examination by the attending physician • Laboratory tests (clinical and biochemical blood tests, urine analysis) • 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) • Echocardioscopy is necessary to assess structural and functional changes in the heart (condition of valves, cardiac muscle, pericardium, pulmonary artery diameter, pressure in the pulmonary artery, mechanical complications of myocardial infarction, heart tumors, etc.); • X-ray of the chest organs in 4 projections; • Coronary angiography to assess the patency of the arteries that supply blood to the heart muscle; • Cardiac catheterization may be required to determine the pressure in the chambers of the heart, and transesophageal echocardioscopy.

A very important question before surgical treatment is to replace anticoagulant therapy, if necessary; on the eve of hospitalization, antiplatelet agents are canceled if the patient receives them.

Hospitalization is carried out in the cardiac surgery department of a multidisciplinary clinic.

The day before surgery, the patient is consulted by an anesthesiologist. Checks height, weight, presence of chronic diseases, allergies to medications, and examines the patient. In the evening, the patient is denied dinner. Before going to bed, you are only allowed to drink. In the morning before the operation, breakfast is canceled, and drinking is also prohibited. Premedication is performed.

Contacting a doctor after the labyrinth operation

After leaving the hospital, you should consult a doctor if the following symptoms appear:

- cough or difficulty breathing;

- Chest pain;

- Signs of infection, including fever and chills;

- Cardiopalmus;

- Redness, swelling, increased pain, bleeding, or any discharge from the surgical incision;

- Nausea and/or vomiting that does not go away after taking prescribed medications and persists for more than two days after leaving the hospital;

- Pain that does not go away after taking prescribed pain medications;

- Coughing up blood;

- Headache or feeling weak;

- Inability to urinate;

- Pain, burning, frequent urination, or constant bleeding in the urine;

- Pain and/or swelling in the legs, calves, and feet;

- Other alarming symptoms.

You need to call an ambulance if any of the following symptoms appear:

- Sudden chest pain;

- Sudden shortness of breath;

- Problems with vision or speech;

- Numbness or weakness on one side of the body.

Surgery through the patient's eyes

In the operating room, the anesthesiologist puts the patient under anesthesia; after the administration of the drugs, there may be slight short-term dizziness, a feeling of chills, or a slight fever. Otherwise, the patient falls asleep unnoticed and wakes up in the intensive care unit (ward). The operation is performed under general anesthesia, so the patient does not feel anything.

Operation “labyrinth” is a combined surgical intervention, i.e. is performed during another heart operation (for example, CABG, for the correction of heart defects), so the time of the procedure cannot be specified precisely; it is different in each specific case, depending on the nature of the operation. On average, the duration is from 2 to 4 hours. In any case, it feels like it lasts a few seconds for the patient.

Possible complications during labyrinth surgery

Complications are rare, but no procedure is guaranteed to be risk-free. Before you undergo surgery, you need to be aware of possible complications, which may include:

- Infection;

- Bleeding;

- Problems associated with anesthesia;

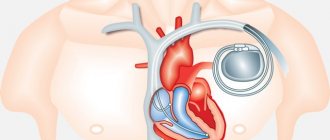

- The need for a permanent pacemaker;

- Kidney or other organ failure;

- Stroke;

- Death.

Some factors that may increase the risk of complications include:

- Existing diseases of the heart, lungs, kidneys;

- Obesity;

- Diabetes;

- Previous breast surgery;

- Use of certain medications.

Forecast

The prognosis is favorable. According to various estimates, sinus rhythm is restored in 88% to 98% of cases. Approximately 2% of patients require postoperative use of antiarrhythmic drugs. The fatal outcome, according to various authors, ranges from 1% to 16%, with an average of approximately 7.5%. In the long-term prognosis, the study revealed two main complications:

• Development of sinus node dysfunction, which required implantation of a pacemaker or, in milder cases, restriction of patients in physical activity. • Postoperative left atrial dysfunction.