May 31, 2021

Most strokes occur due to a blockage in an artery leading to the brain or part of the brain. This disease is called ischemic stroke.

In the article we explain the causes of ischemic stroke, consider its types, as well as diagnostic methods, timing of when to undergo treatment after an ischemic stroke and recovery methods.

What is ischemic stroke

Ischemic stroke occurs when a mechanical obstacle occurs - an atherosclerotic plaque, embolus, thrombus. The clot blocks a blood vessel, cutting off blood flow to brain cells. The most common condition of stroke is the development of cholesterol in the walls of blood vessels (atherosclerosis). Fatty deposits narrow the artery and block blood flow to the brain.

Pathogenesis of ischemic stroke

The difference between an ischemic stroke and a hemorrhagic stroke is that with a hemorrhagic stroke, bleeding into the brain occurs due to a ruptured vessel.

Hemorrhagic stroke occurs less frequently than ischemic stroke:

- ischemic stroke - in 80-85% of patients;

- hemorrhagic - in 10-15% of patients.

Figures and facts

- More than 400,000 strokes are registered annually in Russia, with a mortality rate reaching 35%.

- The overall risk of recurrent stroke in the first 2 years after the first stroke ranges from 4 to 14%.

- With an increase in potassium intake with food (potatoes, beef, bananas), a significant decrease in blood pressure was noted in individuals with moderately elevated levels by 11.4/5.1 mm Hg. Art.

- In patients receiving diuretics (diuretics) for a long time, hypokalemia develops (diagnosed when the potassium concentration is less than 3.5 mmol/l) and an increase in the incidence of cardiovascular complications.

- By increasing daily potassium intake by 10 mmol (for example, when taking the drug potassium and magnesium aspartate), the risk of fatal stroke is reduced by 40%.

Types of ischemic stroke

There are a number of reasons why blockages in the arteries can form, causing an ischemic stroke. Experts identify several types of this disease.

Atherothrombotic stroke

Atherothrombotic ischemic stroke is when a blood clot forms at the site of an atherosclerotic plaque (fatty deposit), which clogs a vessel. Blood does not flow to the brain and because of this, cells die. The extent of brain damage varies from minor to extensive.

Common causes of this type of stroke:

- atherosclerosis.

Cardioembolic stroke

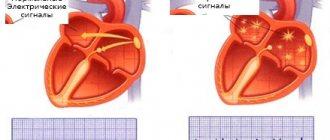

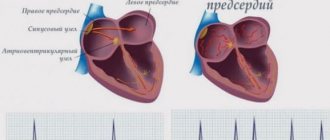

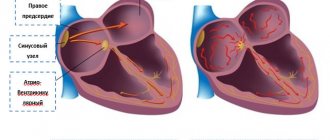

In the artery supplying the brain, a blockage occurs with emboli - this is a substrate that moves along the bloodstream. More often it occurs under abnormal conditions of the functioning of the human heart.

Common causes of this type of stroke:

- atrial fibrillation;

- heart valve disease;

- artificial heart valve;

- chronic heart failure;

- acute myocardial infarction;

- orthopedic surgeries, injuries.

Lacunar stroke

Lacunar ischemic stroke is characterized by damage to small arteries due to prolonged high blood pressure. In the tissues of the gray matter of the brain, softening occurs and a cavity is formed - a “lacuna”.

Common causes of this type of stroke:

- arterial hypertension;

- cerebral atherosclerosis;

- diabetes;

- other reasons.

Hemodynamic stroke

A sharp drop in blood pressure causes a lack of cerebral circulation.

Common causes of this type of stroke:

- acute heart failure;

- myocardial infarction;

- heart rhythm disturbance;

- bleeding;

- vascular collapse.

Hemorheological stroke

Impaired blood flow.

Common causes of this type of stroke:

- uncontrolled use of large diuretics;

- smoking abuse in combination with large doses of coffee and alcohol.

Prognosis and prevention of cardioembolic stroke in atrial fibrillation

V.A. PARFENOV

, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor,

S.V.

VERBITSKAYA ,

First Moscow State Medical University named after. THEM. Sechenov A review of the literature on the prediction and prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation (AF) is presented.

It is noted that the easy-to-use CHA2DS2-VASc scale can well predict the risk of stroke in AF. In patients with one or more risk factors for stroke according to the CHA2DS2-VASc scale, the use of oral anticoagulants is recommended. Data from large randomized trials are presented that show that new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) are not inferior to warfarin or have the advantage of a more significant reduction in the risk of stroke and a less significant risk of major, especially intracranial, bleeding. There has been positive practical experience with the use of dabigatran (Pradaxa®) at a dose of 150 mg or 110 mg twice in patients with AF. In our country, the introduction into neurological practice of new anticoagulants, the use of which does not require control using the international normalizing ratio, will make it possible to more widely prescribe anticoagulant therapy to patients with AF and reduce the incidence of cardioembolic stroke. Atrial fibrillation (AF, atrial fibrillation) is one of the most common heart rhythm disorders; its frequency increases with age; in people over 70 years of age, AF occurs in approximately 5% of cases [1, 2]. Persistent and paroxysmal form of non-valvular AF is one of the most important risk factors for ischemic stroke (IS), increasing the likelihood of its development by 3–4 times [1]. In patients with AF, a slowdown in blood flow occurs, leading to the formation of blood clots mainly in the left atrial appendage, which can cause embolism in the blood vessels of the brain and other organs.

Predicting the risk of stroke in atrial fibrillation

In patients with AF, the risk of stroke increases with increasing age, in the presence of heart failure, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, previous episodes of thromboembolism, mitral valve calcification, or thrombus in the left atrium [2].

In clinical practice, the CHADS2 scale has been used for a long time as the main scale to predict and assess the risk of thromboembolic complications in patients with AF, among whom AI is of leading importance. The abbreviation CHADS2 comes from the first letters of the English names of individual risk factors for stroke: Congestive heart failure - chronic heart failure, Hypertension - arterial hypertension, Age - age over 75 years, Diabetes mellitus - diabetes mellitus, Stroke - AI or transient ischemic attack (TIA) in medical history. In this scale, 2 points are assigned to stroke or TIA (therefore, an index of 2 is assigned next to the letter “S”) and 1 point to other factors (Table 1). The higher the CHADS2 score, the higher the risk of stroke, and vice versa (Table 2).

In recent years, the CHA2DS2-VASc scale [3], which is an extension of the CHADS2 scale to which other independent risk factors for IS have been added, has been proposed and widely introduced into clinical practice (Table 3).

In this scale (in addition to the CHADS2 scale), the following vascular risk factors are used: vascular damage (history of myocardial infarction, peripheral arterial atherosclerosis, aortic atherosclerosis), age 65–74 years, female gender.

If the maximum number of points on the CHADS2 scale is 6, then on the CHA2DS2-VASc scale it is 9. In 2010, the CHA2DS2-VASc scale was included in the recommendations of the European Society of Cardiology [4] for assessing the risk of IS in AF.

The CHA2DS2-VASc scale includes more factors that determine the risk of stroke, its superiority over the CHADS2 scale has been confirmed in several clinical studies, among which a recent large study that included data on 73,538 patients with AF who did not receive anticoagulant therapy is particularly noteworthy [5]. During a year of observation in individuals with “low risk” (score = 0), the frequency of systemic thromboembolic complications according to the CHADS2 scale was 1.67 per hundred patients per year, and according to the CHA2DS2-VASc scale – 0.78. The data obtained demonstrate that patients who were classified as low risk according to the CHA2DS2VASc scale had a truly low risk of developing thromboembolic complications. Analysis of the results of observation of this large group of patients over 10 years shows a significantly higher information content of the CHA2DS2-VASc scale in comparison with the CHADS2 scale. Many patients from the so-called. low-risk groups according to the CHADS2 scale have a fairly high risk of thromboembolic complications. Overall, the CHA2DS2-VASc score is better at predicting stroke risk (Table 4) than the CHADS2 score.

Prevention of cardioembolic stroke

To prevent stroke and other thromboembolic complications (systemic embolism) in AF, until recently, the use of aspirin or indirect anticoagulants (warfarin) under the control of the international normalized ratio (INR) was recommended [6–9]. For patients with AF under 75 years of age who have no history of stroke and are at low risk of developing it (less than 2% per year), aspirin is recommended at a dose of 75–325 mg per day. With a higher risk of stroke in patients with AF (4% per year or more), the prescription of warfarin (with a target INR of 2–3) was considered justified in the absence of contraindications to its use [6, 7].

A meta-analysis of several studies showed that the use of warfarin in AF reduces the risk of stroke by an average of 68% [10]. During the year, treatment with warfarin in 1 thousand patients with AF prevents the development of 31 IS. Major bleeding occurs relatively rarely in 1.3% of cases (in the placebo or aspirin group in 1% of cases) if the INR is maintained in the therapeutic range of 2 to 3. When treating with warfarin, it is necessary to remember its possible interaction with other drugs and foods, the need for regular laboratory monitoring of INR and, on this basis, dose adjustment of the drug. The effectiveness of aspirin in AF is much lower; it reduces the risk of stroke by an average of 21% in patients with AF.

The widespread use of warfarin in our country is limited to a certain extent by the fact that many patients who have undergone IS due to AF refuse treatment with the drug due to the need to regularly visit the clinic to monitor the INR and limit the intake of certain foods and drugs. During follow-up (an average of more than 4 years) of 77 patients who underwent IS due to AF, only 21 patients (27.2%) began to regularly take warfarin and achieved an INR of 2 to 3 [11].

In arterial hypertension, its effective treatment with normalization of blood pressure (BP) reduces the risk of both stroke and bleeding when taking anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents [5]. In approximately one third of patients who have suffered an IS or TIA due to AF, another possible cause of IS is found, for example, significant stenosis of the internal carotid artery. In such cases, combination therapy is possible, for example, carotid endarterectomy and subsequent treatment with anticoagulants.

When treating with antithrombotic drugs, it is necessary to take into account the risk of bleeding, especially intracranial bleeding, which often leads to the death of the patient. The risk of bleeding should be assessed before prescribing anticoagulant therapy in patients with AF. In clinical practice, the HAS-BLED scale is used to assess the risk of bleeding [12], which is included in modern recommendations for the treatment of AF (Table 5).

Currently, the effectiveness of new oral anticoagulants that affect other stages of blood coagulation (Fig. 1) and do not require constant monitoring of the INR, as with warfarin treatment, is being actively studied in patients suffering from AF.

The results of several large randomized trials have shown that new indirect anticoagulants are not inferior to warfarin or even superior to it in preventing stroke, while being characterized by a lower risk of bleeding, especially intracranial. The first of this group of drugs to prove its effectiveness was dabigatran etexilate (dabigatran), which is currently widely used throughout the world for the prevention of stroke in AF.

Dabigatran in stroke prevention

Dabigatran is a direct thrombin inhibitor, the effectiveness and safety of which in the prevention of stroke and thromboembolic complications in patients with AF compared with warfarin was studied in the RE-LY study [13]. The study included patients with AF who had at least one or more risk factors for stroke and systemic embolism: history of stroke or TIA, left ventricular ejection fraction less than 40%, heart failure NYHA class 2 or higher (within 6 months . and more), age 75 years and older, or age 65 years and older in combination with arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus or coronary heart disease. Exclusion criteria for participation in the study were: severe heart valve pathology, the presence of a prosthetic heart valve, ischemic stroke within 14 days before inclusion in the study, severe stroke within 6 months. before inclusion in the study, severe disability due to stroke, high risk of bleeding, creatinine clearance less than 30 ml/min, active liver disease, pregnancy.

The primary objective of the study was to compare the incidence of stroke and systemic embolism while taking dabigatran at a dose of 110 or 150 mg twice daily or warfarin at a dose that maintains an INR of 2 to 3. The primary safety endpoint was the incidence of major bleeding at various treatment regimens according to the frequency of life-threatening hemorrhages. The study included 18,113 patients at 967 centers in 44 countries. The study design involved randomization of patients into three groups: two groups received the study drug dabigatran etexilate at a dose of 150 mg or 110 mg twice a day, in the third group patients received the comparison drug warfarin. The groups were homogeneous in size and did not differ from each other in basic clinical characteristics, some of which are shown in Table 6.

During an average of two years of follow-up, major vascular events (stroke, systemic embolism) developed significantly less frequently in the group of patients taking dabigatran 150 mg twice daily (1.11% per year) than in the group of patients receiving warfarin (1. 71% per year). In the group of patients receiving dabigatran 110 mg twice daily, the rate of stroke and embolic events was 1.54% per year, which was comparable to the rate of events in the warfarin group. Mortality (from all causes) at one year was 4.13% in the warfarin group and trended lower in the dabigatran 110 mg group (3.75%) and in the dabigatran 150 mg group (3.64%). Mortality from cardiovascular diseases during the year was 2.69% in the warfarin group, it tended to decrease (2.43%) in the dabigatran 110 mg group and was significantly lower (2.28%) in the dabigatran 150 mg group. The incidence of major bleeding during the year during warfarin therapy was 3.36%, tended to decrease in the dabigatran 150 mg group (3.11%) and was significantly lower (2.71%) in the dabigatran 110 mg group. The incidence of life-threatening bleeding within a year was 1.24% in the group of patients taking dabigatran 110 mg twice a day, 1.49% in the group receiving dabigatran 150 mg twice a day, and was significantly higher (1.85% ) in the warfarin group. The incidence of hemorrhagic stroke within a year was 0.12% in the dabigatran 110 mg group, 0.10% in the dabigatran 150 mg group and was significantly higher (0.38%) during warfarin therapy.

The main adverse events during the entire treatment period are presented in Table 7, which shows that there were no significant differences between the groups in the main adverse events, with the exception of dyspepsia, which was slightly higher in the group of patients taking dabigatran.

Among the patients participating in the study, almost every fifth suffered a stroke or TIA; using randomization, these patients, along with the rest, were divided into three main groups; Thus, 1,195 patients took dabigatran 110 mg twice a day, 1,233 took dabigatran 150 mg twice a day, 1,195 patients took warfarin. In the subgroup of patients with a history of stroke or TIA, the incidence of stroke and systemic embolism per year was 2.38%, which was significantly more common than in patients without a history of stroke or TIA - 1.22%. Analysis of the study results in this subgroup of patients showed that the main patterns observed in the entire group of patients are preserved; There was no effect of previous stroke or TIA on the main differences noted between the groups of patients receiving dabigatran or warfarin therapy [15]. In patients with a history of stroke or TIA, there was a trend towards a lower incidence of major events (stroke, systemic embolism) with dabigatran compared with warfarin, with a significantly lower incidence of events with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily (Table 1). 8).

In patients who had a stroke or TIA, there was a significant reduction in the incidence of hemorrhagic stroke when taking dabigatran compared with treatment with warfarin, with the greatest benefit in reducing the incidence of hemorrhagic stroke observed in the dabigatran 110 mg twice daily group (Table 9). The incidence of intracranial hemorrhage was also higher in the subgroup of patients taking warfarin. The incidence of all strokes tended to be higher in the subgroup of patients receiving warfarin, due to a higher incidence of hemorrhagic stroke.

In a subgroup of patients who had a stroke or TIA, treatment with dabigatran 110 mg twice daily was associated with a reduction in the incidence of death from cardiovascular causes, as well as a reduction in the incidence of life-threatening bleeding compared with warfarin. The incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding was comparable in the subgroups of patients taking dabigatran 110 mg twice daily or warfarin. In patients receiving dabigatran therapy at a dose of 150 mg 2 times a day, gastrointestinal bleeding occurred more often than in the warfarin group. The incidence of myocardial infarction did not differ significantly between patients with stroke or TIA based on therapeutic regimens.

Rivaroxaban in stroke prevention

Rivaroxaban (a direct factor Xa inhibitor) at a dose of 20 mg or 15 mg (in patients with creatinine clearance 30–50 ml/min) per day was studied in patients with non-valvular AF compared with warfarin in the ROCKET AF trial [14]. The study included AF patients with moderate and high risk of stroke; more than half of the patients suffered a TIA or stroke or an episode of systemic embolism. The study included 14,264 patients (60% men, 40% women, mean age 73 years), with a mean follow-up of 707 days. The primary endpoint of the study was the incidence of major vascular events (IS, hemorrhagic stroke, systemic embolism) in patients taking rivaroxaban or warfarin. The safety of treatment was assessed by the incidence of clinically significant hemorrhagic events.

The study found that major vascular events occurred at a rate of 1.7% per year in patients receiving rivaroxaban and 2.2% per year in patients receiving warfarin (p < 0.001). Clinically significant hemorrhage occurred at an incidence of 14.9% per year in patients taking rivaroxaban and 14.5% per year in patients taking warfarin (p = 0.44). In the group of patients taking rivaroxaban, intracranial hemorrhages (0.5%; in the warfarin group - 0.7%, p = 0.02) and fatal hemorrhages (0.2%; in the warfarin group - 0.5) were less likely to develop. %, p = 0.003).

In the subgroup of patients who did not have a history of TIA, IS, or episodes of systemic embolism, the incidence of major events was 2.57% when taking rivaroxaban and 3.61% in the warfarin group, which proves the superiority of rivaroxaban over warfarin in the primary prevention of IS, TIA and systemic embolism. In this subgroup, clinically significant hemorrhages occurred less frequently (1.67%) with rivaroxaban than with warfarin (2.86%).

In the subgroup of patients with a history of IS, TIA, or an episode of systemic embolism, the incidence of major events was not significantly different and reached 4.8% and 4.9%, respectively, when using rivaroxaban and warfarin, respectively. In this subgroup, clinically significant hemorrhages occurred at a rate of 3.5% with rivaroxaban and 3.9% with warfarin.

Apixaban in stroke prevention

Apixaban (a direct factor Xa inhibitor) was studied for the prevention of thromboembolic events in patients with non-valvular AF in the AVERROES [15] and ARISTOTLE [16] studies.

The AVERROES trial [15] examined the effectiveness of apixaban and aspirin in 5,599 patients (mean age 70 years, 41% women and 59% men) with non-valvular AF and one or more additional risk factors for stroke (median CHADS2 score of 2 points). , for whom it was impossible to prescribe warfarin therapy for a number of reasons. Apixaban was used at a dose of 5 mg twice daily (in 94% of cases) or 2.5 mg twice daily (in 6% of cases in patients who met 2 or more of the following criteria: age 80 years or older, weight 60 kg or less, creatinine level 133 mmol/l or more). Aspirin was used at a dose of 81–324 mg per day.

The study was stopped early because there was strong evidence of superiority of apixaban over aspirin. The incidence of stroke or systemic embolism in the apixaban group was 1.6% per year, which was significantly lower than in the aspirin group, in which it reached 3.7% per year. Apixaban was significantly more effective than aspirin in preventing severe and fatal stroke, the incidence of which was 1% in the apixaban group and 2.3% per year in the aspirin group. The incidence of clinically significant bleeding did not differ significantly between treatment groups and was 1.4% per year in the apixaban group and 1.2% per year in the aspirin group.

In a small group of patients who had an IS or TIA, the incidence of recurrent IS or systemic embolism was 2.5% in patients in the apixaban group and significantly higher - 8.3% - in the aspirin group. However, the incidence of clinically significant bleeding did not differ significantly and was 3.5% per year in the apixaban group and 2.7% per year in the aspirin group.

The ARISTOTLE trial [16] compared the effectiveness of apixaban and warfarin in preventing stroke or systemic embolism in 18,201 patients (mean age 70 years, 35% women, 65% men) with AF who had at least one additional risk factor for stroke. Apixaban was used in dosages of 5 mg or 2.5 mg (in patients with creatinine clearance 30-50 ml/min) 2 times a day, warfarin - in doses necessary to achieve an INR of 2.0-3.0. The average follow-up time for patients was approximately 2 years.

The incidence of stroke or systemic embolism was 1.27% in the apixaban group, which was significantly lower than in the warfarin group - 1.6%. In the apixaban group, the incidence of hemorrhagic stroke was significantly reduced (by 49%) and, to a lesser extent (8%), the incidence of IS or unspecified stroke. The incidence of deaths in the apixaban group was 3.52% per year, in the warfarin group it was significantly higher - 3.94% (p = 0.047). The incidence of serious bleeding was 2.13% in the apixaban group and was significantly higher – 3.09% – in the warfarin group (p < 0.001). The advantage of apixaban over warfarin was also noted in the group of patients who had a TIA or IS. Modern approach to stroke prevention

Based on the results of recent studies, recommendations have been made [4] for the prevention of stroke and other thromboembolic complications in patients with AF using the CHA2DS2-VASc scale (Table 10).

As can be seen from the data presented in the table, oral anticoagulants are recommended as treatment for patients with one or more points on the CHA2DS2-VASc scale.

Among the new oral anticoagulants, dabigatran (Pradaxa) is currently the most widely used. When treated with dabigatran - unlike warfarin - there is no need to select the dose of the drug, regular laboratory (hematological) monitoring, restriction of intake of many foods and drugs, which improves the quality of life of patients with AF [16]. Dabigatran is prescribed in a fixed dose of 150 mg or 110 mg twice daily. If laboratory (hematological) monitoring of dabigatran is necessary, partially activated thromboplastin time, thrombin time and other coagulogram indicators can be used [17].

When choosing a dose of dabigatran (110 mg or 150 mg twice daily), one should in each case take into account the possible risk of developing IS, systemic embolism and bleeding. Dabigatran at a dose of 150 mg twice a day has an advantage in the prevention of the development of IS and systemic embolism compared with warfarin; at a dose of 110 mg twice a day it is characterized by a lower incidence of bleeding of various locations, including intracranial. In most cases of AF, more reliable prevention of stroke and systemic embolism is necessary, so dabigatran 150 mg twice daily is preferable. However, in some patients at high risk of bleeding, it is advisable to use a dose of 110 mg twice daily. Currently, only a high dose (150 mg twice daily) of dabigatran is recommended for stroke prevention in AF in the United States [18]. A quantitative analysis of all possible advantages and disadvantages of different doses of dabigatran demonstrates the advantage of a large dose [19].

One question that was not answered by the RE-LY study concerns the timing of dabigatran administration in patients with AF who have had an IS or TIA. Is it possible to prescribe dabigatran in the earliest period after the development of IS or TIA, which is advisable in most cases? The RE-LY study enrolled patients who had suffered a stroke or TIA only after 2 weeks. from the moment of illness, so the question of prescribing dabigatran for up to 2 weeks. after IS and TIA remains controversial and requires further research in this direction.

The advantage of treatment with dabigatran and other new oral anticoagulants over warfarin is of particular importance in cases where patients live in regions where laboratory monitoring of INR during warfarin treatment is poorly established [20, 21]. Unfortunately, in our country, neurologists, when caring for patients who have suffered an IS or TIA due to AF, often face significant problems due to the lack of an established laboratory service necessary to monitor the INR when prescribing warfarin therapy [22]. Therefore, the use of new oral anticoagulants, the treatment of which does not require dose selection or regular laboratory monitoring, will allow neurologists to more effectively carry out secondary prevention of cardioembolic stroke in patients with non-valvular AF.

It has now been proven that the use of the easy-to-use CHA2DS2-VASc stroke risk scale allows predicting the likelihood of thromboembolic events in patients with AF. In patients with one or more risk factors for stroke according to the CHA2DS2-VASc scale, it is recommended to use warfarin or newer oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban). Currently, positive global practical experience has been accumulated in the use of dabigatran in doses of 110 mg or 150 mg twice a day to prevent stroke, systemic embolism and reduce cardiovascular mortality. In our country, a significant proportion of patients who have suffered ischemic stroke or TIA due to AF do not take warfarin due to the difficulty of regular INR monitoring. The introduction of new anticoagulants into neurological practice, the administration of which does not require INR control, will make it possible to more widely prescribe anticoagulant therapy to patients with AF and reduce the incidence of cardioembolic stroke.

Literature

1. Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke 1991;22:983-988. 2. Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation Working Group. Independent predictors of stroke in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Neurology 2007;69:546-554. 3. Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJ. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest 2010;137:263-272. 4. European Heart Rhythm Association; European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2010;31:2369-2429. 5. Olesen JB, Lip GY, Hansen ML et al. Validation of risk stratification schemes for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation: national cohort study. BMJ 2011;342:d124. 6. Sacco RL, Adams R, Albers G et al. Guidelines for Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke: Co-Sponsored by the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline. Stroke 2006;37:577-617. 7. European Stroke Organization (ESO) Executive Committee; ESO Writing Committee. Guidelines for management of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25:457-507. 8. Suslina Z.A., Fonyakin A.V., Geraskina L.A. and others. Practical cardioneurology. M., IMA-PRESS, 2010. – 304 p. 9. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ et al. Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2011;42:227-276. 10. Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation: analysis of pooled data from five randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:1449-1457. 11. Verbitskaya S.V., Parfenov V.A. Secondary prevention of stroke in outpatient settings. Neurological Journal 2011;1:17-21. 12. Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R et al. .A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest 2010;138:1093-1100. 13. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1139-1151. 14. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:883-891. 15. Connolly SJ, Eikelboom J, Joyner C et al. Apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;364:806-817. 16. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:981-992. 17. Van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S et al. Dabigatran etexilate—a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost 2010;103:1116-1127. 18. Beasley BN, Unger EF, Temple R. Anticoagulant options—why the FDA approved a higher but not a lower dose of dabigatran. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1788-1790. 19. Pink J, Lane S, Pirmohamed M, Hughes DA. Dabigatran etexilate versus warfarin in the management of non-valvular atrial fibrillation in the UK context: quantitative benefit-harm and economic analyses. BMJ 2011;343:d6333. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6333. 20. Kamel H, Johnston SC, Easton JD, Kim AS. Cost-Effectiveness of Dabigatran Compared With Warfarin for Stroke Prevention in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and Prior Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. Stroke 2012;43:881-883. 21. Harris K, Mant J. Potential impact of new oral anticoagulants on the management of atrial fibrillation-related stroke in primary care. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:647-655. 22. Parfenov V.A., Khasanova D.R. Ischemic stroke. M., MIA, 2012. – 288 p.

What is a transient ischemic attack (TIA)

Transient ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) is a short-term disruption of brain function when blood circulation stops in one area, and is restored after a few hours. Local ischemia lasts no more than 24 hours, then it is reversible.

The main difference between TIA and ischemic stroke is that the first disease does not cause any changes in the brain. Scientists are currently examining the brain to determine whether TIA actually causes permanent changes to the brain.

New research tells a different story:

- TIA up to 5 minutes - no changes in the brain;

- TIA from 6 to 30 minutes - changes in the brain in every third person;

- TIA from 12 to 24 hours - changes in the brain of ⅔ patients.

It is important to understand that a transient ischemic attack is a precursor to a stroke, so you need to track it, see the subtle symptoms and consult a doctor as soon as possible to prevent stroke. From 10% to 40% of TIAs end in stroke, the risk is greatest in the first week after a transient ischemic attack.

At first glance, the symptoms of a TIA are indistinguishable from a stroke:

- darkening of the eyes;

- decreased vision;

- loss of vision in one eye;

- other visual impairments;

- speech disturbance, as if “porridge in the mouth”;

- inability to pronounce a word;

- inability to formulate words and sentences in your head;

- sensory disturbance;

- movement disorders;

- weakness in the body;

- numbness of the face;

- numbness of the upper and lower extremities;

- dizziness;

- falling without loss of consciousness;

- disorientation in time and space;

- memory impairment for recent events;

- loss of balance.

Clinical picture

Computed tomography of the brain. Hypertensive subcortical hematoma in the right frontal lobe

Computed tomography of the brain of the same patient 4 days after surgery - removal of an intracerebral hematoma of the right frontal lobe

If symptoms of acute cerebrovascular accident appear, you should immediately call emergency help in order to begin treatment as early as possible.

Symptoms

Stroke may manifest as cerebral

and

focal

neurological symptoms.

General cerebral symptoms

strokes are different. This symptom may occur in the form of impaired consciousness, stupor, drowsiness, or, conversely, agitation; a short-term loss of consciousness may also occur for several minutes. A severe headache may be accompanied by nausea or vomiting. Sometimes dizziness occurs. A person may feel a loss of orientation in time and space. Possible vegetative symptoms: feeling of heat, sweating, palpitations, dry mouth.

focal symptoms appear

brain damage. The clinical picture is determined by which part of the brain is affected due to damage to the blood vessel supplying it.

If a part of the brain provides the function of movement, then weakness in the arm or leg develops, including paralysis. Loss of strength in the limbs may be accompanied by a decrease in sensitivity in them, impaired speech, and vision. These focal stroke symptoms are mainly associated with damage to the area of the brain supplied by the carotid artery. Muscle weakness (hemiparesis), speech and pronunciation problems, decreased vision in one eye and pulsation of the carotid artery in the neck on the affected side are characteristic. Sometimes there is unsteadiness of gait, loss of balance, uncontrollable vomiting, dizziness, especially in cases where the blood vessels supplying the areas of the brain responsible for coordinating movements and a sense of body position in space are affected. “Spotty ischemia” occurs in the cerebellum, occipital lobes and deep structures and brain stem. Attacks of dizziness in any direction are observed when objects rotate around a person. Against this background, there may be visual and oculomotor disturbances (strabismus, double vision, decreased visual fields), unsteadiness and instability, deterioration in speech, movements and sensitivity.

Causes of stroke

Factors that influence the development of ischemic stroke, increase the likelihood of the disease occurring, experts divide into two groups: those that can be influenced and, thanks to proper treatment, prevent a stroke, and those that cannot be influenced, but with proper prevention the risks can be reduced.

The first group (cannot be influenced) includes the following symptoms:

- floor;

- age;

- genetics - first-degree relatives who had a stroke.

The second group (can be influenced) includes:

- arterial hypertension (high blood pressure);

- diabetes;

- TIA and/or previous stroke;

- obesity;

- cardiac ischemia;

- lipid metabolism disorder;

- carotid artery stenosis;

- heart rhythm disturbance - atrial fibrillation;

- heart failure;

- smoking;

- alcohol abuse;

- use of certain medications;

- severe stress.

Having these diseases and habits, it is necessary to consult a specialist to prevent a stroke and reduce the risks of it happening.

Risk factors

Risk factors are various clinical, biochemical, behavioral and other characteristics that indicate an increased likelihood of developing a certain disease. All areas of preventive work are focused on controlling risk factors and their correction both in specific people and in the population as a whole.

- High cholesterol and LDL (low-density lipoprotein) levels in the blood

- Arterial hypertension

- Diabetes

- Heart diseases (arrhythmia, etc.)

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Excess weight

- Age

- Smoking

- Drugs

- Alcohol

- Blood clotting disorders

- TIA (transient ischemic attack) is a significant predictor of the development of both cerebral infarction and myocardial infarction

- Sleep apnea

- Previous history of stroke, heart attack, or TIA

- Carotid artery disease (Asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis, etc.)

- Peripheral vascular disease

- Fabry disease.

Many people in the population have several risk factors simultaneously, each of which can be moderately expressed. There are scales that allow you to estimate your individual risk of developing a stroke (as a percentage) over the next 10 years and compare it with the average population risk for the same period. The most famous is the Framingham scale.

Scientists in Gothenburg found that the rs12204590 mutation near the FoxF2 gene is, in their opinion, associated with an increased risk of stroke.

If a stroke occurs - assessment of the person’s condition, symptoms and first aid

If you notice the first symptoms, which is typical for an ischemic stroke, then you need to call an ambulance as soon as possible. A quick response will save time, and therefore increase the chance of reducing the various consequences of this unforeseen disease.

When diagnosing yourself, you need to pay attention to the following signs - what is included in an ischemic stroke, symptoms:

- weakness, loss of sensation, numbness in the face, arms or legs. Most often on one side of the body;

- decrease or loss of vision;

- loss of speech, difficulty pronouncing a word or sentence, impossible to understand someone else's speech;

- severe headache without any reason, which does not go away with the use of medications that previously helped;

- memory loss;

- it is difficult to navigate in space and perceive what is happening;

- nausea;

- vomit;

- swallowing disorder;

- loss of balance for no apparent reason.

The above signs of ischemic stroke are quite difficult to remember. To make it easier for you, experts have developed a special test that helps identify stroke symptoms and quickly provide assistance for ischemic stroke. It is called FAST - after the first abbreviations of human body parts.

FAST = FAST

Face - face

Arm - hand

Speech - speech

Time - time

We have described how to use the test in the instruction table:

| Part of the body | What to do | If it's a stroke, then... |

| Face | Ask the person to smile or show their teeth | An asymmetry appears on the face: the lips on one side of the face will rise in a smile, and on the other they will be lowered down. |

| Hand | Ask the person to raise both arms and hold them there for 5 seconds. | One hand will go down at once |

| Speech | Ask the person to say a simple phrase, for example, “the sun is bright outside.” | A person may not understand what you asked to do, and if he understands, the spoken phrase will sound incomprehensible, incoherent, and illegible. |

| Time | Call an ambulance if you see any of the signs above. | It is important not to waste time and seek help as quickly as possible. |

Hospitalization - treatment of ischemic stroke

After a person is in the hospital, doctors conduct a full examination to determine the general condition of the patient and give him an accurate diagnosis - what was it, an ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, or perhaps the person has a completely different disease.

Diagnosis of ischemic stroke is carried out using diagnostic procedures:

- computed tomography (CT);

- magnetic resonance imaging (MRI);

- Doppler ultrasound (USDG).

After the diagnosis has been established, taking into account the chosen rehabilitation strategy and the person’s condition, the patient is placed in a neurological, neurosurgical or intensive care unit, where doctors provide treatment and recovery after an ischemic stroke and prescribe medications.

At the first stages, doctors of different specialties begin to work with a person. Treatment after an ischemic stroke includes:

- neurologist;

- ophthalmologist;

- endocrinologist (if necessary);

- psychologist;

- speech therapist;

- orthopedist;

- exercise therapy specialist;

- masseur;

- physiotherapist;

And basic therapy is carried out, where doctors provide external respiration function, if necessary, monitor blood pressure, correct elevated body temperature, and reduce cerebral edema.

Diagnostics

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the most important diagnostic tests for stroke. In most cases, CT allows one to clearly differentiate “fresh” cerebral hemorrhage from other types of strokes; MRI is preferable for identifying areas of ischemia, assessing the extent of ischemic damage and penumbra. These studies can also detect primary and metastatic tumors, brain abscesses and subdural hematomas. If there is a stiff neck but no papilledema, a lumbar puncture will provide a rapid diagnosis of cerebral hemorrhage in most cases, although there is still a slight risk of brain herniation syndrome. In cases where embolism is suspected, lumbar puncture is necessary if anticoagulants are to be used. Lumbar puncture is also important for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and, in addition, can be of diagnostic value in neurovascular syphilis and brain abscess. If CT or MRI is not available, echoencephalography and lumbar puncture should be performed.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnostic characteristics of strokes[38]

| Symptoms | Ischemic cerebral infarction | Brain hemorrhage | Subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| Previous transient ischemic attacks | Often | Rarely | None |

| Start | Slower | Fast (minutes or hours) | Sudden (1-2 minutes) |

| Headache | Weak or absent | Very strong | Very strong |

| Vomit | Unusual except for brainstem lesions | Often | Often |

| Hypertension | Often | Almost always available | Infrequently |

| Consciousness | May be lost for a short time | Usually long term loss | There may be a short-term loss |

| Rigidity of the neck muscles | Absent | Often | Always |

| Hemiparesis (monoparesis) | Often, from the very beginning of the disease | Often, from the very beginning of the disease | Rarely, not from the very beginning of the disease |

| Speech impairment (aphasia, dysarthria) | Often | Often | Very rarely |

| Liquor (early analysis) | Usually colorless | Often bloody | Always bloody |

| Retinal hemorrhage | Absent | Rarely | May be |

On the spot

It is possible to recognize a stroke on the spot, immediately; For this, three main methods of recognizing stroke symptoms are used, the so-called “ USP”

" To do this, ask the victim:

- U

-

smile

. With a stroke, the smile may be crooked, the corner of the lips on one side may be directed downward rather than upward. - Z

-

talk

. Say a simple sentence, for example: “The sun is shining outside the window.” With a stroke, pronunciation is often (but not always!) impaired. - P

-

raise

both hands. If your arms don't rise at the same rate, this could be a sign of a stroke.

Additional diagnostic methods:

- Ask the victim to stick out his tongue. If the tongue is curved or irregular in shape and falls to one side or the other, then this is also a sign of a stroke.

- Ask the victim to stretch his arms forward, palms up, and close his eyes. If one of them begins to involuntarily “move” sideways and downward, this is a sign of a stroke.

If the victim finds it difficult to complete any of these tasks, you must immediately call an ambulance

and describe the symptoms to the doctors who arrived at the scene. Even if the symptoms have stopped (transient cerebrovascular accident), there should be one tactic - emergency hospitalization; old age and coma are not contraindications to hospitalization.

There is another mnemonic rule for diagnosing a stroke: U.D.A.R.

:

- U

-

Smile

After a stroke, the smile becomes crooked and asymmetrical; - D

-

Movement

Raise both arms and both legs up at the same time - one of the paired limbs will rise slower and lower; - A

-

Articulation

Say the word “articulation” or several phrases - after a stroke, diction is disrupted, speech sounds inhibited or simply strange; - R

-

Decision

If you find violations in at least one of the points (compared to the normal state), it’s time to make a decision and call an ambulance. It is necessary to tell the dispatcher what signs of a stroke (STROK) were identified, and a special resuscitation team will be sent.

Prevention and treatment of complications

Complications can occur after both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. Most often, neurological symptoms in ischemic stroke are not as severe as in hemorrhagic stroke, so the main thing for doctors is to combat complications and correct treatment after an ischemic stroke.

A major ischemic stroke affects the large arteries that supply blood to the brain; due to lack of nutrition, one of the brain hemispheres may be affected. Each affected hemisphere of the brain has its own consequences.

| Ischemic stroke (right side) consequences | Ischemic stroke (left side) consequences |

|

|

There are several types of complications that require immediate proper treatment:

Brain swelling

If this complication exists, then doctors try to relieve brain swelling - they use hormonal therapy, place the head in an elevated position, and relieve pain and cramps. Sometimes decompressive surgery is necessary to remove part of the skull bone and avoid squeezing the brain.

Inflammatory processes in the lungs

Inflammation in humans can occur in several cases when swallowing is impaired and food enters the respiratory tract, or from prolonged immobilization and suppression of the cough reflex. Doctors relieve inflammation with antibiotics and other drug therapies.

Inflammation of the urinary tract

Inflammation can begin due to the fact that a person, for example, has a urinary catheter installed. Inflammation can also be relieved with the help of antibiotics and other medications.

Deep vein thrombosis

The disease occurs when the deep veins of the lower extremities are blocked by blood clots. To avoid blood clots in the early stages, a person is given physical therapy and compression garments are used.

Stiffness in the joints

When the limbs remain immobilized for a long time, stiffness occurs in the joints. They are treated with passive physical therapy of paralyzed limbs to avoid the development of contractures.

Colon dysfunction

Intestinal dysfunction occurs when there is difficulty in bowel movements or absence of stool. This problem is solved with a special diet, which includes foods rich in fiber. If the problem is more serious than a lack of diet, then they resort to enemas or laxatives.

Bedsores

They arise from impaired blood supply in places where bone structures are close to the surface of the skin. Most often, bedsores form on the back of the head, shoulder blades, elbows, sacrum, knees, and heels.

Prevention of the formation of bedsores includes a constant change in the position of the human body, proper hygienic treatment of the skin, regular daily examination of the body, proper bedding - not crumpled, dry, clean, without small debris, massage of the skin surfaces.

If bedsores do appear, they are treated using special solutions, ointments, and bandages.

First aid for stroke

In the case of a stroke, the most important thing is to get the person to a specialized hospital as quickly as possible, preferably within the first hour after symptoms are noticed. It should be borne in mind that not all hospitals, but only a number of specialized centers are equipped to provide proper modern stroke care. Therefore, attempts to independently transport a patient to the nearest hospital during a stroke are often ineffective, and the first action is to call emergency services for medical transport.

Before the ambulance arrives, it is important not to allow the patient to eat or drink, since the swallowing organs may be paralyzed, and then food entering the respiratory tract can cause suffocation. At the first signs of vomiting, the patient's head is turned to the side so that the vomit does not enter the respiratory tract. It is better to lay the patient down with pillows under his head and shoulders, so that the neck and head form a single line, and this line makes an angle of about 30° to the horizontal. The patient should avoid sudden and intense movements. The patient is unbuttoned from tight, obstructive clothing, his tie is loosened, and his comfort is taken care of.

In case of loss of consciousness with absent or agonal breathing, cardiopulmonary resuscitation is started immediately. Its use greatly increases the patient's chances of survival. Determining the absence of a pulse is no longer a necessary condition for starting resuscitation; loss of consciousness and absence of rhythmic breathing are sufficient. The use of portable defibrillators further increases survivability: when in a public place (cafe, airport, etc.), first aid providers need to ask the staff if they have a defibrillator or nearby.

Life after ischemic stroke - rehabilitation and prevention of recurrent stroke

Proper rehabilitation plays the main role in a person’s recovery after a stroke and his return to independent life.

Rehabilitation sets itself the task of restoring the patient’s lost functions to the extent possible and adapting him to the changed living conditions.

The principles of rehabilitation include several important aspects:

- early onset;

- A complex approach;

- individual rehabilitation program;

- intermediate and long-term goals;

- multidisciplinary team of doctors;

- a person’s motivation to recover;

- active patient participation;

- continuity;

- involving relatives and friends in the rehabilitation process.

You can learn more about why an integrated approach to rehabilitation is more effective and how doctors work in a multidisciplinary team here.

Ischemic stroke. Stages of rehabilitation

The consequences and recovery after an ischemic stroke depend on the time of initiation of rehabilitation. The sooner you start working with specialists, the better the result will be, and the likelihood of complications will decrease.

Rehabilitation after an ischemic stroke includes two stages: hospital, during hospitalization, and home, after discharge from the hospital. After leaving the hospital, a person can take quotas and go to a sanatorium, undergo rehabilitation procedures at a clinic, or seek help from specialists for rehabilitation at home.

Recovery periods after ischemic stroke

Treatment

Treatment of stroke includes a set of emergency measures and a long recovery period (rehabilitation), carried out in stages.

Treatment of stroke should be aimed at restoring damaged areas of nervous tissue and protecting nerve cells from the spread of the so-called “vascular catastrophe.” Restoration of damaged areas is carried out using a group of special drugs - neuroreparants. And healthy nerve cells are protected by neuroprotective drugs. Certain drugs successfully combine both of these effects, and therefore can be used for complex treatment of stroke. To restore lost body functions, the patient may be prescribed physical therapy, massages, speech therapy and other exercises.

Urgent Care

At the prehospital stage of medical care, the patient’s hemodynamic parameters should be assessed; if there is a pronounced increase in blood pressure (more than 220/120 mmHg), measures should be taken to reduce it gradually. A rapid decrease in pressure will lead to deterioration of the patient's condition and loss of cerebral perfusion.

In the case of a stroke, the most important thing is to get the person to hospital as quickly as possible, preferably within the first hour after symptoms are noticed. It should be borne in mind that not all hospitals, but only a number of specialized centers are equipped to provide proper modern stroke care. Therefore, attempts to independently transport a patient to the nearest hospital during a stroke are often ineffective.

Before the ambulance arrives, it is important not to allow the patient to eat or drink, since the swallowing organs may be paralyzed, and then food entering the respiratory tract can cause suffocation.

At the first signs of vomiting, the patient's head is turned to the side so that the vomit does not enter the respiratory tract. It is better to lay the patient down with pillows under his head and shoulders, so that the neck and head form a single line, and this line makes an angle of about 30° to the horizontal. The patient should avoid sudden and intense movements. The patient is unbuttoned from tight, obstructive clothing, his tie is loosened, and his comfort is taken care of.

Resuscitation measures

Making the correct diagnosis and detecting the exact location of the stroke, as well as data on the volume of damaged tissue, allows you to choose the right treatment tactics and avoid more severe consequences. In addition to interviewing and examining the patient, special examinations of both the brain and the heart and blood vessels are necessary.

Resuscitation measures should be aimed at maintaining adequate hemodynamics and oxygenation.

Pharmacotherapy

Drugs are prescribed according to treatment standards and according to the decision of the attending physician.

Features of patient care

Stroke is often accompanied by pneumonia and bedsores, which require constant care, turning from side to side, changing wet underwear, feeding, bowel cleansing, and vibration massage of the chest.

Post-stroke rehabilitation

In the world practice of rehabilitation treatment after stroke, the leading place is occupied by an interdisciplinary approach, based on which the treatment (therapy) process is led by several specialists, mainly a physiotherapist, occupational therapist, and speech therapist.

- A physiotherapist works to restore motor functions.

- An occupational therapist deals with a person’s adaptation to everyday life after a stroke.

- The speech therapist is involved in the restoration of speech and swallowing (if the patient has aphasia and dysphagia).

The human brain has a certain natural ability to recover, thanks to the creation of new connections between healthy neurons and the formation of new information circuits. This property of the brain is called neuroplasticity and can be stimulated during the rehabilitation process. One of the key factors in the effectiveness of any rehabilitation program is the regular implementation of a carefully organized, individually selected set of exercises - that is, the general principle of teaching a person a new skill.

New rehabilitation methods include robotic treatments, for example, HAL therapy, which, through repeated targeted repetition of movements, help activate the mechanism of neuroplasticity.

During rehabilitation in the post-stroke period, various auxiliary methods are used, in particular pharmacological, therapeutic exercises, exercises with biofeedback (for various reactions, including EEG, ECG, breathing, movements and support reaction);

In 2021, Russian scientists announced that they had managed to develop a dental device that helps restore the speech of a patient who has suffered a stroke.

In the post-stroke period, the risk of post-stroke depression (PD) is high. It has a negative impact on the rehabilitation process, quality of life, somatic health, and contributes to the manifestation of concomitant mental illnesses (primarily anxiety disorders). PD significantly worsens survival prognosis. Thus, patients with PD die on average 3.5 times more often within 10 years after a stroke than patients without symptoms of depression. According to statistics, the prevalence of PD is 33%; on average, every third stroke patient is affected by it.

Among the mental factors influencing the occurrence of post-stroke depression are premobid personality traits and the patient’s attitude towards his illness. Factors associated with depression after stroke include speech problems, social isolation, and poor functional status. PD can also have an organic origin and be determined by the location of the brain lesion. There is an opinion that the severity of depression is higher when the stroke is localized in the frontal lobe and basal ganglia of the left hemisphere. Depression may also be a response to drug therapy.

Treatment of PD is carried out through antidepressants, psychostimulants, electroconvulsive therapy (especially for drug intolerance and severe depression refractory to treatment), transcranial magnetic stimulation, and cognitive behavioral psychotherapy.