The Innovative Vascular Center has all the necessary technologies for the treatment of acute and chronic occlusion of the inferior vena cava. Our specialists have successful experience in solving this complex problem.

Acute thrombosis of the inferior vena cava requires treatment in a specialized vascular surgery hospital. The goal of treatment is to restore the patency of the IVC. This problem is successfully solved using endovascular surgery methods. There are modern thrombolytic drugs and endovascular probes for removing thrombotic masses.

Causes of SVPV

The main cause of superior vena cava syndrome is obstruction, which is based on pathological processes such as:

- germination of the vein wall by a cancerous tumor;

- compression of the vein from the outside;

- thrombosis of a valveless vessel.

In 90% of cases, the cause of obstruction is the presence of a malignant process in the body. At the same time, lung cancer accounts for 85% of tumors (squamous or small cell cancer). In more rare cases, the cause is lymphoma and lymphogranulomatosis (tumor disease of the lymphatic system). Metastases of other malignant neoplasms (breast, testicle) contribute to the development of SVPV.

Among the causes of Kava syndrome, the following should also be highlighted:

- benign tumors;

- aortic aneurysm;

- enlargement of the thyroid gland;

- fibrous mediastinitis (inflammatory process in the mediastinal tissue).

Blockage of blood outflow from the valveless vessel and the head is fraught with the development of a number of pathophysiological effects. Venous return to the right ventricle is impaired and cardiac output is reduced. Systemic hypotension (decreased arterial pressure) and increased venous pressure in the SVC system are also observed, which is fraught with the development of cerebral vascular thrombosis. Due to a decrease in the arterial-venous gradient, irreversible changes in the brain region may develop.

In lung cancer, the patency of a valveless vessel, as a rule, is preserved, despite the fact that invasion has already occurred. Only 10-20% of patients with tumor SVPV live more than 2 years. The life expectancy of such patients, according to statistics, does not exceed 10 months.

A characteristic feature of kidney cancer is the formation of tumor thrombosis of the inferior vena cava (up to 25%), in some cases spreading to the right atrium [10, 12, 14]. Almost 100 years have passed since 1913, when A. Berg [9] was the first in the world to report nephrectomy in combination with tumor thrombectomy from the inferior vena cava (IVC). However, only in 1972 was the rationality of an aggressive surgical approach to the management of such conditions demonstrated (in combination with radical nephrectomy, thrombectomy from the IVC provides a 5-year survival rate of 55% of patients) [17]. Despite this, especially in the case of extended IVC thrombosis, there are still a large number of unresolved surgical issues (access, exposure, feasibility of using cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), which makes this problem relevant to this day.

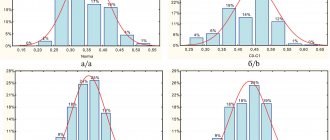

R. Neves and H. Zinck [16] in 1987 for kidney cancer proposed dividing tumor invasion of the IVC and right atrium into

4 categories (Fig. 1),

Figure 1. Types of tumor invasion of the IVC [15, 16] (schemes). Types III-IV are considered the most surgically labor-intensive.

In such situations, in the absence of distant metastases (except for single pulmonary metastases), despite the increase in surgical risk, radical surgery using cardiac surgical technologies is advisable, which provides the only chance to prolong the patient’s life [1-17].

We have experience in the surgical treatment of 7 patients with types I-II tumor invasion of the IVC and 3 patients with kidney cancer and tumor thrombosis of the right atrium (type IV). Here's an example.

Patient E., 53 years old, was operated on at the Russian Scientific Center for Surgery named after. acad. B.V. Petrovsky on June 26, 2011 with a diagnosis of B1 of the upper pole of the right kidney T3bN2M0. Tumor thrombosis of the IVC and right atrium (surgeon - Academician of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences Yu.V. Belov). Radical nephrectomy, aortocaval lymph node dissection, thrombectomy from the right atrium and IVC were performed (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Computer tomograms and stages of surgery in patient E. (photos). a — computed tomograms of the abdominal and thoracic cavity. A tumor of the right kidney with thrombosis of the IVC and right atrium is visualized.

Figure 2. Computer tomograms and stages of surgery in patient E. (photos). b — surgical approach — sternolaparotomy.

Figure 2. Computer tomograms and stages of surgery in patient E. (photos). c — aortocaval lymphadenectomy.

Figure 2. Computer tomograms and stages of surgery in patient E. (photos). d — mobilization of the liver.

Figure 2. Computer tomograms and stages of surgery in patient E. (photos). e — longitudinal cavatomy and removal of tumor thrombus.

Figure 2. Computer tomograms and stages of surgery in patient E. (photos). e — suture of the IVC.

Figure 2. Computer tomograms and stages of surgery in patient E. (photos). g - photograph of a tumor thrombus.

Access to the heart and organs of the retroperitoneal space was achieved using a total longitudinal sternolaparotomy. The pericardium was opened and placed on supports. Sagittal diaphragmotomy to the mouth of the IVC after preliminary suturing of the phrenic vein. The peritoneum of the right lateral canal is incised, the duodenum and ascending colon are mobilized and retracted medially. In the projection of the right kidney, a tumor of 12×10 cm in size is determined to be of dense elastic consistency, emanating from the upper pole of the kidney. The liver was completely mobilized due to the dissection of all its ligaments in such a way that it remained fixed only by the hepatoduodenal ligament (the latter was taken into a tourniquet) and the orifices of the hepatic veins. Typical aortocaval lymph node dissection - a package of lymph nodes enlarged to 2 cm (6 pieces) is removed from the area of the aortocaval window. The IVC is expanded to 6 cm in its retrohepatic section: palpation reveals a thrombus of dense elastic consistency. The right renal artery was sutured and divided at the ostium with 3/0 Etibond thread. The ovarian vein was sutured and crossed at its mouth with a 4/0 prolene thread. The adrenal vein was sutured and divided at the site of its entry into the IVC using a 4/0 Prolene thread. On palpation of the right atrium, a tumor thrombus was 2 cm above the mouth of the IVC. It was decided to operate without IR. A large aortic clamp clamped the right atrium above the thrombus. Clamp on the IVC in the infrarenal region, clamp on the left renal vein. Tighten the tourniquet on the hepatoduodenal ligament. The liver is retracted medially. Longitudinal cavatomy along the anterolateral wall of the retrohepatic segment of the IVC from its mouth to the right renal vein (the incision was made lateral to the mouth of the right hepatic vein). The head of the thrombus was “born” from the right atrium. A 12×5.5 cm long thrombus was removed from the IVC as a single block. The mouth of the right renal vein was excised due to intimate adhesion of the thrombus to the vein wall. The IVC incision is sutured with a longitudinal continuous suture using 4/0 Prolene thread. After preventing material and air embolism, all clamps are removed and blood flow is started through the IVC. Atrial fibrillation and hypotension up to 60/40 mm Hg. A single shock from the defibrillator restored stable sinus rhythm. Hemodynamics are stabilized at 120/80 mmHg. Art. Next, the tumor was mobilized en bloc with the adrenal gland and paranephrium using the LigaSure device. The right ureter and ovarian veins are ligated in the lower third separately with 3/0 Vicryl thread. The drug has been removed. Hemostasis. Drainage to the operation area, into the pericardium, into the pleural cavities. Typical wound closure. Blood loss 4500 ml. Liver ischemia 18 min. Postoperative course without complications.

Histological examination: the kidney revealed sclerosis and hyalinosis of individual glomeruli with the presence of serous cysts lined with thickened epithelium. In the renal pelvis, tumor growth was observed, represented by proliferations of cancer cells with light cytoplasm and a dense hyperchromic nucleus. Cancer metastases were found in the hilum lymph nodes and in the tissue of the upper pole of the kidney. An adrenal gland with the correct structural structure without tumor tissue growing into it. Conclusion: renal cell carcinoma (clear cell type) with metastases to the hilum lymph nodes and kidney tissue.

It is necessary to focus on some fundamental aspects of surgical treatment of such a disease (types of tumor invasion of the IVC III-IV).

The surgical approach must be adequate, creating convenient exposure of both the right atrium and the IVC along its entire length. The authors of [15] suggest using the so-called “chevron” (“Mercedes”) cut (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Surgical approach (modified from [15], diagram). We consider longitudinal sternolaparotomy more “profitable” and safe as universal access to all organs of the thoracic, abdominal and retroperitoneal space. In addition, the access makes it possible to perfectly expose the IVC distal to its “cross” for its possible cannulation with a second venous cannula (since the typical cannulation site of the second “vein” is made by a tumor thrombus). We consider thoracotomy in combination with lumbotomy proposed by researchers [7] to be a less convenient access. Academician M.I. Davydov [4] suggests performing similar operations from a median laparotomy; he has developed access to the right atrium and the mouth of the IVC through a sagittal diaphragmotomy. In this article, we deliberately do not consider patients with types I-II tumor invasion of the IVC, since they are successfully operated on using laparotomy or thoracofrenolaparotomy, and the use of IR is not required.

It is important to completely mobilize the liver, which should be performed so that only the hepatic veins serve as points of fixation of the liver to the IVC (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Mobilization of the liver and direction of cavatomy [15] (diagram). In this case, the liver remains fixed from below only to the hepatoduodenal ligament, and from above - to the hepatic veins.

Nephrectomy can be performed either before or after IVC thrombectomy [7, 12, 15]. In types I-II and in some cases in type III tumor thrombus, the latter can be removed without the use of IR. In such patients, the feasibility of blood-saving technologies is extremely relevant.

In this regard, we consider it very important, in addition to the use of Cell-Saver, to use the Pringle maneuver [15], i.e. compression of the hepatoduodenal ligament with the blood vessels passing through it (v. portae and a. hepatica) with a tourniquet.

Liver ischemia that occurs when the hepatoduodenal ligament is clamped minimizes blood loss from the hepatic veins during cavatomy. An additional reduction in blood loss during the main stage of the operation can be achieved, among other things, through preliminary ligation of the renal artery [13]. The use of an IR device with blood sampling into the cardiotomy reservoir using coronary suction makes thrombectomy safe in terms of hemorrhagic complications.

There are publications in the world literature concerning the surgical tactics of treating such patients using various schemes of complete cardiopulmonary bypass with or without circulatory arrest [14], as well as using isolated right heart bypass [7] and venovenous bypass [11] . There are no problems with arterial cannulation - the ascending aorta is cannulated in a typical place as standard. To reach the calculated performance of the IR device, the right atrium is cannulated either with a special “basket-like” venous cannula [12], or the superior vena cava is cannulated, and a second venous cannula is placed either in the femoral vein or in the IVC below the thrombus palpated in its renal segment [ 15], or into the right atrium [10]. The main stage of intervention on the IVC is performed under conditions of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest of 15-18 °C [12, 13], or under conditions of moderate hypothermia 30-32 °C using the Pringle maneuver [15]. The use of deep hypothermia ensures a bloodless surgical field, minimizes the risk of warm ischemia of visceral organs, and reduces the likelihood of material tumor embolism. At the same time, deep hypothermic circulatory arrest requires longer CPB time spent on cooling and warming the patient, and intra- and postoperative coagulopathy is more likely [12]. Thrombectomy from the right atrium is performed under conditions of cold crystalloid cardioplegia in a stopped heart [10, 12, 15]. G. Bisleri et al. [10], using moderate hypothermia during arrest of blood flow through the organs and thrombectomy from the right atrium, propose to perfuse the brain according to the superior vena cava - aortic arch scheme (the latter is clamped distal to the left common carotid artery and proximal to the arterial cannula). After thrombectomy, a second venous cannula is placed in the IVC, the clamps are removed from the aorta, and body warming begins. Very interesting is the proposal of a team of researchers led by P. Shatapathy to perform thrombectomy from the right atrium on a beating heart under normothermic conditions using a right heart bypass (cannulation according to the scheme of the SVC - IVC below its hepatic segment - the right pulmonary artery) [7]. Academician M.I. Davydov [4] has experience in more than 50 thrombectomies from the right atrium on a beating heart through laparotomy access with sagittal diaphragmotomy. In rare cases where the tumor prolapses into the right ventricle, we consider this procedure dangerous, since fatal thromboembolism from tumor masses is possible.

According to a modern review of the literature [12], radical nephrectomy with thrombectomy from the IVC is accompanied by 2.7-13% operative mortality and 5-year survival of 30-72% of patients.

Thus, in our opinion, in the case of tumor invasion of the mouth of the inferior vena cava and the right atrium, the use of artificial circulation for “safe” thrombectomy could not be more justified. However, indications for its use, options for connecting a heart-lung machine, and the level of hypothermia require clarification.

Symptoms of SVC syndrome

Symptoms of superior vena cava syndrome develop against the background of venous hypertension. Signs of pathological disorders directly depend on the progression of obstruction, its degree and area of localization. The degree of progression of collaterals (side or bypass tracts of blood flow) is also important. It is also a component of SVPV.

The course of the disease can be either slowly progressive or acute. Complaints can be quite varied, ranging from changes in appearance and slight dizziness to convulsions and fainting. On physical examination, veins in the neck, arms, and chest wall are swollen and dilated. The picture of the disease in many patients is blurred. Physical diagnosis includes the Pemberton test - raising your arms up. With occlusion of a valveless vessel, cyanosis of the skin of the neck and face is observed, as well as injection of conjunctival vessels.

Clinical signs of superior vena cava syndrome in cancer are conventionally divided into several groups. The result of stagnation in superficial and deep structures:

- swelling in the arms, face and body;

- asphyxia (suffocation) – when swelling moves to the vocal cords;

- when the capillaries narrow, cyanosis develops, which is characterized by an earthy-pale skin color (occurs against the background of lymphostasis - a pathological accumulation of protein-rich fluid).

Congestion in the brain area is accompanied by general cerebral symptoms: characteristic shortness of breath, constant headaches, and frequent attacks of suffocation. With prolonged disturbances, worsening laryngeal edema is noted.

As a result of ongoing disorders, dramatic changes occur in the brain area, which are fraught with the development of emotional fatigue and drowsiness. Attacks of suffocation are accompanied by loss of consciousness, which is a sign of cerebral hypoxia, which develops against the background of ongoing circulatory disorders. Among the most common manifestations of the pathological process, one should highlight the pronounced occurrence of auditory hallucinations and severe confusion.

Among the manifestations of cranial nerve disorders, diplopia (double vision) and a pronounced deterioration in hearing qualities should be highlighted. Such signs are caused by nerve disorder and are accompanied by decreased visual function and tearfulness. It is possible that intraocular pressure may increase.

In order to more fully characterize the patient’s condition with SVPV, the third group of clinical signs caused by the underlying disease should be studied. They manifest themselves in the form of cough, cachexia and hemoptysis. Superior vena cava syndrome in oncology is accompanied by nasal and esophageal bleeding, which occurs due to thinning of the venous walls. During physical activity, hand fatigue occurs quite quickly. It becomes difficult to perform even minor physical work, which is associated with a rush of venous blood to the head. Heart pain, increased heart rate and compression behind the chest are the consequences of disruption of the blood supply to the heart muscle and swelling of the mediastinal tissue.

Complications

Often, with SVPV, there is the development of bleeding (esophageal, nasal or pulmonary), which develops as a result of rupture of the vascular walls. Due to impaired venous outflow in the head area, cerebral symptoms develop:

- confusion and fainting;

- cramps and weakness of the limbs;

- frequent pain in the head area.

When the nerves are damaged, exophthalmos develops (mono- or binocular anterior displacement of the eyeball), diplopia (double vision), lacrimation, blurred vision and rapid eye fatigue. Hearing impairment, tinnitus and auditory hallucinations are possible.

Diagnosis of Cava syndrome

There are two main stages in diagnosis. This is an initial examination in non-core clinics. The basis is the classic clinical picture and the result of radiography in lateral and direct projection. If there are pathological abnormalities, there is additional darkening in the image. If SVPV is suspected, the patient is sent to a specialized medical facility.

Diagnosis of superior vena cava syndrome includes:

- FBS (fibre-optic bronchoscopy)

– is prescribed for topographic-anatomical localization of the pathological process. - An incisional or puncture biopsy

is performed when peripheral lymph nodes are affected. - Angiography

is used in rare cases and is aimed at determining the extent of the obstruction.

The effectiveness of diagnostic measures at the second stage of the examination is determined by the proportion of morphologically verified diagnoses. Conducted studies prove that the ability to perform certain diagnostic procedures is associated with the degree of progression.

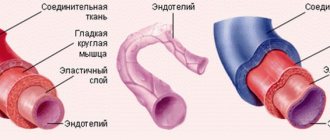

Anatomy of the vena cava

The upper one is located in the chest cavity, namely in its upper part. It is formed by the fusion of two veins - the brachiocephalic veins (right and left). It originates at the level of the first rib to the right of the sternum, goes down, flows at the level of the third right rib into the right atrium. It is adjacent to the right lung, and the aorta passes to the left of it. Behind the superior hollow is the root of the right lung, at the level of the second right rib it is covered by the pericardium. Before its entrance into the pericardial cavity, two veins flow into it: the azygos and the accessory hemi-unpaired.

The inferior vena cava begins in the abdominal cavity. It is formed at the confluence of the iliac veins, goes up, deviates to the right from the aorta towards the diaphragm. It is located in the retroperitoneal space behind the internal organs. Through an opening in the diaphragm it is directed into the chest cavity, from there it goes to the pericardium and flows, like the superior hollow, into the right atrium. The following veins drain into the IVC:

- hepatic;

- diaphragmatic lower;

- adrenal gland right;

- renal;

- right ovarian or testicular;

- lumbar

The inferior vena cava is usually divided into three sections: infrarenal, renal and hepatic.

Treatment of superior vena cava syndrome in cancer patients

In case of serious condition of patients, emergency care is required. In this case, there is no time left to conduct a full examination and determine the morphology of the tumor. Treatment measures include taking steps to improve venous outflow through the valveless vessel. There is a need to eliminate respiratory failure, restore cerebral circulation and relieve possible pulmonary edema.

In severe cases, treatment is prescribed aimed at combating dangerous symptoms - the doctor prescribes antitumor drugs that are effective against most malignant neoplasms. With the right approach, the patient's condition quickly normalizes.

Features of treatment of superior vena cava syndrome:

- Symptomatic

. Includes taking measures aimed at increasing the functional reserves of the body. The doctor prescribes a low-salt diet, diuretics, oxygen inhalations and glucocorticoids. - Pathogenetic

. It is prescribed after stopping the main cause of the pathological process. For lymphogranulomatosis, lymphoma and lung cancer, radiation and polychemotherapy are performed. In case of thrombosis, thrombectomy is performed, thrombolytic therapy is prescribed, or a segment of the SVC is resected.

In the case of extravasal compression, radical surgery is performed, which involves excision of a mediastinal tumor, lymphoma, cysts, benign neoplasms, etc. If radical surgery is not possible, then palliative procedures are resorted to (bypass surgery, SVC stenting, percutaneous balloon angioplasty).

At the Medscan clinic in Moscow, treatment of superior vena cava syndrome is carried out on the basis of international protocols. The medical center uses the latest expert-class equipment. Doctors with extensive practical experience are constantly retrained to improve their level of competence. The results of treatment for SVPV primarily depend on the effectiveness of radical therapy for the underlying disease. Superior vena cava syndrome is unfavorable in pediatric oncology. Eliminating the causes of Kava syndrome allows you to stop its consequences and prevent the development of possible complications.

Treatment of pathology

The goal of treatment is to relieve the patient of the symptoms of the pathology. But there is another, primary goal - saving lives. This is exactly what needs to be done at the first stage of treatment. The situation of a patient with primary pathology is extremely serious; he requires oncological resuscitation.

If pathology is the first symptom of cancer, then treatment prospects are good, since a number of forms of oncology are cured under the influence of chemotherapy.

If after surgery and therapeutic treatment are completed, but the pathology is not defeated due to the fact that the oncology is progressing, there are practically no prospects for a cure. Here we need to strive to improve the quality of life and prolong it.

At the Onco.Rehab integrative oncology clinic, all conditions have been created for the treatment of various pathologies and their symptoms. We help our patients.