Depending on age, the frequency of bowel movements, consistency and color of stool are different. In infants, the frequency of bowel movements can be up to 7-8 times a day and up to 1 time every 2-4 days, and this is the norm. In children of the 2nd year of life, the number of bowel movements is 1-2 times a day. The stool should be well-formed and of soft consistency, the number of bowel movements is determined by the child’s individual rhythm - the baby is healthy and there is no need to worry.

If the baby's stool is liquid or looks like "sheep" feces, it is advisable to consult a pediatrician and examine the child as planned.

The color of the stool may vary, mainly depending on what foods the child eats. But if the baby’s stool has become black and sticky, it may be bleeding (stomach or intestinal); if it has become colorless, it may be a liver or gallbladder disease.

URGENT CARE

Call an ambulance if:

- The child's stool has become black and sticky

- a child's stool is profusely mixed with scarlet blood (bleeding from the lower gastrointestinal tract, mainly the large intestine)

THE DOCTOR'S CONSULTATION

Contact your pediatrician if:

- the skin and mucous membranes turn yellow and the stool is discolored

- the child's stool is large, greasy and has an unpleasant odor (a sign of poor digestion)

ATTENTION!

If the stool is copious, greasy, or foul-smelling, this is a sign of poor digestion. A doctor's consultation is required .

| ASK YOURSELF A QUESTION | POSSIBLE REASON | WHAT TO DO |

| The general condition is good, there is a tendency to constipation, the child has pain when defecating, and a few minutes later there is blood on the toilet paper and a little in the stool | Anal fissure | Consultation with a pediatrician for examination and examination |

| Change in stool after taking medications (antibiotics), becoming more liquid | Side effects of drugs | Consultation with a doctor to discontinue the medication or reduce the dose and course of treatment |

| The child feels well but has dark-colored stools (is taking iron supplements, or has eaten blueberries or dark green vegetables) | Effect of medications or food on stool | The baby is fine, no need to worry |

| The baby's stools have become clayey and light in color, his urine has darkened, his skin has a yellowish tint, and his sclera (the whites of his eyes) have turned yellow. | Viral hepatitis (older children) Congenital liver disease or biliary atresia (newborns) | Call your pediatrician immediately, for examination and treatment, the child may be hospitalized. Before the doctor arrives, keep the baby calm. |

| The stool is faintly colored, smells unpleasant, is greasy and profuse | Insufficient digestion | Consultation with a pediatrician (or gastroenterologist ) for examination and treatment prescription |

| An increase in temperature, a violation of the general condition, an admixture of dark burgundy or scarlet blood in the stool | Inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, bleeding from different parts of the intestine | Call emergency services immediately ; hospitalization for examination and treatment is possible. |

| Stools resemble coffee grounds or are black and sticky | Bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract (esophagus or stomach), called melena | Call emergency services immediately ; hospitalization for examination and treatment is possible. |

FOR INFORMATION

Stool color and consistency

The color and consistency of your child's stool may change from time to time - this is normal. However, traces of fresh blood or black, sticky stools may be signs of bleeding and require urgent evaluation. The sudden appearance of loose stools, with or without mucus, indicates diarrhea. If the stool is copious, greasy, smells bad, and is faintly colored, these are signs of poor digestion of food. In all these cases, an examination by a pediatrician is required. If your child's stool is light, clay-colored and his urine has become dark, viral hepatitis is possible - call your pediatrician immediately .

Minor changes in stool color are related to diet. In breastfed children, the stool is soft, almost liquid, reminiscent of light mustard. It may contain particles that look like seeds. With artificial feeding, the stool is yellowish-brown or yellow, denser, but still no denser than putty. If the stool is very hard and dry, this may be due to a lack of fluid or excess fluid loss, for example, with sweat due to an increase in temperature, etc. If the child has eaten a large portion of vegetables or other difficult-to-digest foods, digestion may slow down and the stool may be very dark colors. Beetroot or red-colored foods may cause your stool to become reddish (for the same reason, your urine may turn pink).

The stool turns blue, purple, or another shade if the child tastes crayons. In this case, as soon as the colored substance is released from the intestines, the stool returns to its normal color. If the child's condition worsens, call the pediatrician immediately - poisoning is possible.

I will try to describe a typical baby with allergic proctocolitis.

Usually this is a well-developed, well-fed baby with excellent health, in whom, from the age of 2-3 months, parents began to notice a slight increase in stool (may or not) and streaks of scarlet blood in the stool.

Often there is also a lot of mucus in the stool.

Typically, with typical proctocolitis there is no obvious colic, but there may be restlessness when passing stool

Allergic proctocolitis can develop both in a breastfed and artificially fed child.

In a general stool analysis, you can find a large number of leukocytes in the stool (although this sign is nonspecific), and there may be a completely normal analysis.

In a general blood test, hemoglobin may be slightly reduced and the number of eosinophils may be increased, but everything may be fine.

It is with this picture that one should think about allergic proctocolitis.

Associated symptoms

If a child develops loose stool mixed with blood, it is necessary to determine other accompanying symptoms. This will help in the future to describe to the doctor a complete picture of the baby’s condition and provide him with full assistance.

Body temperature

If a child’s usual stool is replaced by diarrhea with blood without fever, this may be evidence of:

- allergic reaction;

- indigestion after overeating;

- a sudden change in the usual diet;

- early incorrect introduction of complementary foods;

- severe stress, fear;

- mild food poisoning.

However, such a disorder can also be caused by more serious reasons. Therefore, the appearance of even minor blood impurities in the stool is a good reason to consult a doctor.

Vomiting and diarrhea with blood in a child with a fever is the first sign of an acute intestinal infection. Such symptoms are usually accompanied by weakness, dizziness, body aches, pain, rumbling and cramps in the abdomen, and a false urge to defecate.

Change in color of stool, presence of mucus

If the disorder develops, you should take a very close look at the stool. Sometimes parents mistake incompletely digested red foods (tomatoes, beets, paprika, blueberries, currants, etc.) for blood streaks.

The most dangerous condition that requires immediate medical attention is red diarrhea in children. The appearance of scarlet blood can mean rapid massive hemorrhage in the colon or other parts of the intestine.

The presence of liquid stool that is dark brown or black in color (so-called melena) indicates the presence of a source of bleeding in the upper gastrointestinal tract or inflammatory changes in the walls of the small intestine.

Foamy yellow-green, greenish, light brown and other colors of diarrhea in a child with streaks of blood and mucus usually develops against the background of an acute intestinal infection.

Anal itching

If bloody diarrhea in a child is accompanied by itching in the anus, this may be evidence of injury to the internal hemorrhoid.

Which allergen to exclude?

The most common allergen is cow's milk protein.

Cow's milk is the basis for the preparation of standard milk formulas for babies, but dairy products can also be present in the diet of a nursing mother, later penetrating into breast milk.

By the way: Back in 1921 (almost a hundred years ago!) the possibility of allergens from the mother’s diet entering breast milk was proven.

There are about 25 different allergen proteins in cow's milk, some of which are found in the milk of other animals - goats, sheep, and so on.

The most significant allergens are beta-lactoglobulin and casein.

Therefore, to check the breastfeeding of children, the mother switches to a dairy-free diet, and bottle-fed children are transferred to a special formula, where milk protein is broken down to the smallest fragments (deep hydrolysates) or absent (a solution of amino acids instead).

Amino acid mixtures are the most non-allergenic and safe even for severe allergy sufferers, but are much more expensive than hydrolysates.

During the trial diet, mothers often exclude beef/veal for a while - 10% of children have a chance of cross-allergy.

Advantages of contacting MEDSI

- Help from experienced doctors.

Pediatric coloproctologists, gastroenterologists and psychologists work with patients. They know exactly how to treat constipation in a child in accordance with the reasons that provoked it - Diagnostic capabilities.

The clinic can conduct complex examinations. They allow you to identify the causes of the pathology, find out how and what caused constipation in a child, and help him as soon as possible - An integrated approach to solving the problem.

Doctors not only recommend diet and exercise. If necessary, specialists prescribe laxatives, antispasmodics, as well as agents that stimulate the evacuation of feces (enemas and suppositories). All drugs are selected individually - Preventing complications.

To prevent the undesirable consequences of constipation, regular examinations by a coloproctologist are mandatory. - Comfort of visiting clinics.

We provide timely consultations without queues at a time convenient for patients

To make an appointment, just call 8 (495) 7-800-500. Our specialist will answer all questions and suggest the optimal time to visit the doctor. Recording is also possible through the SmartMed application.

What to do if a trial diet excluding cow's milk protein does not work?

- if the child is breastfed, reconsider the mother’s diet (what if hidden milk protein still appears) or try to exclude other, rarer allergens - soy, chicken eggs, wheat

- if the child is on hydrolyzate, switch to an amino acid mixture

Please note - soy is also a common allergen in itself (up to 0.5% of the population), and in people with an existing allergy to milk protein, the frequency of cross-allergy to soy is from 15% to 50%.

We also take into account other reasons for the periodic appearance of blood in the stool:

- Dermatitis around the anus

- Fissure of the anus - usually in the presence of dense stool in a baby, usually on artificial feeding. A visible fissure in the anus in the presence of soft stool does not exclude allergic proctocolitis.

- Infections. Usually, if a child has such classic intestinal infections as salmonellosis or dysentery, the child has obvious signs of intoxication, and with campylobacteriosis, the baby’s well-being may be relatively good.

- Blood clotting disorders (very rare, usually there are other manifestations of bleeding)

Gymnastics

To prevent the pathological condition, walking and running, swimming, exercises to strengthen the abdominal press, squats, and bends are useful.

It is believed that mobile, active children suffer less from constipation. To prevent the pathological condition, walking and running, swimming, exercises to strengthen the abdominal press, squats, and bends are useful.

If your child is already suffering from bowel problems, it is recommended to start the day with simple morning exercises. Massage may also be helpful.

It is important to pay attention to the general change in the baby’s behavior.

The child should be taught to go to the toilet at approximately the same time and encouraged for following the daily routine (motivated and praised).

It is also important to create a favorable environment in the toilet. Nothing should distract the child from the act of defecation or frighten him in the bathroom.

What if the complaints disappeared during the diet, but doubts remained?

It is possible to reintroduce the allergen protein: the previous complaints have reappeared - doubts have been resolved.

Important: this should not be done in case of acute and severe allergic conditions; anaphylactic shock is possible!

But proctocolitis is not an acute, not serious condition, so the experiment is possible.

The prognosis for non-IgE conditions is usually good.

Complaints will disappear even if you do nothing at all... but it’s better not to do that!

Often, when discussing complaints from a baby, parents remember that older children also had blood in the stool in the first months of life, but then disappeared on their own. With hindsight we understand that most likely they also had allergic proctocolitis.

In most children with proctocolitis, complaints disappear before the age of one year, with FPE between the ages of 1 and 3 years, with FPIES between the ages of 1 and 5 years.

Very rarely, allergic proctocolitis persists into older age or occurs for the first time in older children or adults.

In these cases, it is very difficult to exclude a certain trigger food product; drug treatment is often required - corticosteroids, aminosalicylates. The range of conditions for a differential diagnosis by a doctor is also different.

6, total, today

Diet

What can you give your child for constipation?

This question interests many parents. The fight against the problem should begin not with taking medications, but with changing your diet.

Necessary:

- Increase fluid intake

- Set up fractional meals

- Add fiber-rich foods to your diet

You should teach your child to drink plain, clean water. Typically, for children over 3 years of age, 2-3 glasses of water per day are sufficient. Sugary carbonated drinks, coffee and tea should be avoided. This is due to the fact that they have a pronounced diuretic effect and stimulate constipation and dehydration.

Cool water, which children drink in the morning on an empty stomach, is especially beneficial. Gradually, the temperature of the liquid can be reduced. The following drinks also have a laxative effect:

- beet juice

- fermented milk (kefir, fermented baked milk, etc.)

- chamomile decoctions

- tea with dill

Important! They should be introduced into the diet gradually, starting with small amounts. Otherwise, you can provoke digestive breakdown.

You should teach your child to drink plain, clean water. Typically, for children over 3 years of age, 2-3 glasses of water per day are sufficient.

Treatment of constipation in children also involves the introduction of foods with a laxative effect into the diet, which include:

- legumes

- nuts

- prunes and dried apricots

- plum

- beets

- dates

They are also included in the diet gradually and under the supervision of a doctor. Cereal porridges may be useful: oatmeal, buckwheat, wheat, pearl barley. It is advisable to avoid rice, pears, sweets, baked goods, animal fats, and flour products. They have a fixing effect.

What else should I feed my baby to avoid constipation?

The answer to this question should be given by a pediatrician.

Diagnosis of anal fissure

Anal fissure is diagnosed by a pediatric proctologist or surgeon.

Even when parents first contact a doctor, a specialist may suspect the presence of this disease. The doctor pays attention to the child’s characteristic complaints, the influence of provoking factors, and the history of the development of the pathological process. A digital rectal examination is required to make a definitive diagnosis. However, in order not to cause psycho-emotional discomfort in the presence of severe pain, the doctor may first limit himself to a simple examination of the anal area. Sometimes the defect can be identified immediately.

If a rectal examination is not performed immediately, it will be postponed to the next visit. The fact is that anal fissures are often a consequence of other proctological diseases, which may not be diagnosed without a full examination. This means that the pathology of the rectum will steadily progress.

To comprehensively assess the patient’s condition, the following tests are performed:

- General blood and urine analysis. Allows you to identify concomitant diseases, primarily anemia, inflammation.

- Coprogram is a microscopic analysis of feces, which is especially important if dysfunction of other parts of the gastrointestinal tract is suspected.

- Blood chemistry. Detects metabolic changes in the body.

- Ultrasound of the abdominal organs. Detects abnormalities in the development of internal organs.

If a concomitant pathology is identified, its treatment is carried out in parallel, which helps to avoid recurrence of the anal fissure.

Description of the disease

Anal fissure develops less frequently in children compared to adult patients.

This is due to a small number of provoking factors and rapid restoration of the mucous membrane with proper treatment. The disease affects boys and girls equally often. Anal fissure is rarely encountered by children under the age of 3-5 years, whose stool is extremely rarely thick. An exception may be cases of congenital malformations of the rectum.

Depending on the nature of development, an anal fissure can be:

- acute;

- chronic.

The latter option most often occurs in adolescents in the absence of proper treatment for the disease at the earliest stages of its development.

In such cases, sometimes it is even necessary to surgically remove the affected tissue, and only then carry out conservative therapy. Depending on the location, anal fissures are divided into 3 types:

- rear;

- front;

- lateral.

The pathological process can occur with or without spasm of the anal sphincter. Prolonged tonic contraction of the annular muscles of the anus aggravates the course of the disease. Against the background of spasm, the child has bowel movements less often. This leads to hardening of the stool, which subsequently further injures the rectal mucosa. The child has a fear of going to the toilet. This closes a vicious circle, causing a deterioration in the patient’s well-being.

E.K.Petrosyan, P.V.Shumilov, A.P.Ponomareva, O.S.Tatarenova, L.M.Karpina, M.B.Sagalovich, Yu.G.Mukhina Russian State Medical University of Roszdrav, Moscow Russian Children's Clinical Hospital, Moscow

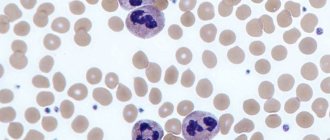

Blood in the stool in children is a serious symptom of a number of serious diseases. The appearance of blood in the stool requires extensive clinical and instrumental examination and detailed differential diagnosis. In childhood, the frequency of this symptom is low. Blood in the stool is observed in 0.3% of children admitted to the hospital [1]. Blood in the stool can have a different character and volume, which is primarily determined by the localization of intestinal bleeding and the nature of the disease (Fig. 1). Bleeding from the colon is characterized by unchanged blood in the stool in the form of a bright red admixture of blood on the surface or mixed with stool. For small intestinal bleeding, melena (black or tarry stool) is more typical, since in this case the blood is subject to enzymatic or bacterial fermentation. In a number of patients, the admixture of blood is so minimal that it is not visually detected, and the clinical picture is dominated by anemic symptoms in the form of pallor, fatigue and other symptoms of sideropenia, and blood in the stool is determined only by laboratory methods. In this case they talk about “hidden blood”. When conducting a differential diagnostic search in a child with blood in the stool, in addition to the location of bleeding, the amount of blood, changes in stool characteristics and the general condition of the patient, attention should be paid to the patient’s age, as this may be of decisive importance. The range of causes of blood in the stool in a child differs significantly from that in adults and has a number of age-related characteristics (Fig. 2). Systemic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases as the cause of blood in the stool are more common in older children, but can occur at different ages. Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic disease in which diffuse inflammation localized within the mucous membrane (less often penetrating into the submucosal layer) affects only the colon at different lengths. The prevalence of UC is 30-240 per 100,000 population, and this pathology is constantly getting younger. In Germany, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) affects approximately 200,000 people, of which 60,000 are children and adolescents, and approximately 800 new cases of IBD in pediatric practice are reported annually [2]. Currently, there is a significant increase in the prevalence of severe inflammatory bowel diseases, mainly among the urban population of industrialized countries. UC usually manifests itself in high school and adolescence, although cases of the onset of the disease have also been described in children of the first year of life. Among the clinical manifestations of UC, the most striking is the intestinal syndrome, which has its own characteristics and depends on the localization of the pathological process. Blood in the stool occurs in 95-100% of patients with UC. The amount of blood can vary - from streaks to profuse intestinal bleeding. Diarrhea is observed in 60-65% of patients. The frequency of stools during diarrhea ranges from 2-4 to 8 or more times a day. Diarrhea is typical for common forms. Its intensity depends on the extent of the lesion. The most pronounced diarrheal syndrome is when the right parts of the colon are affected (total or subtotal colitis). In left-sided forms, diarrhea is moderate. Tenesmus - false urges with the release of blood, mucus and pus ("rectal spitting") with virtually no feces - are characteristic of UC and indicate high activity of inflammation in the rectum. Constipation, usually combined with tenesmus, is characteristic of limited distal forms of UC and is caused by spasm of the intestinal segment lying above the affected area. Abdominal pain is not as typical of UC. Spastic pain associated with defecation may occasionally occur. Extraintestinal systemic manifestations are characteristic of UC, occur in 5-20% of cases and usually accompany severe forms of the disease. All extraintestinal symptoms can be divided into two large groups: immune (autoimmune) origin and those caused by other causes and mechanisms, in particular malabsorption syndrome and its consequences, prolonged inflammatory process, and hemocoagulation disorders. Cases of kidney damage in UC have been described. The most common are urolithiasis and secondary amyloidosis, but there are also cases of glomerulonephritis, in particular its mesangioproliferative variant. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a severe chronic systemic autoimmune disease of connective tissue and blood vessels. Systemic lupus erythematosus is characterized by the formation of circulating autoantibodies, predominantly antinuclear, and the formation of circulating immune complexes deposited on the basement membranes of various organs, which causes their damage and an inflammatory reaction. Morphologically, this manifests itself in the form of fibrinoid swelling of the connective tissue and musculoskeletal system, the connective tissue of the endothelium of small vessels or the mesothelial layer of the serous membranes. Systemic lupus erythematosus most often affects adults (patients under 16 years of age account for 15-20% of all patients), especially young women. For children, SLE is a rare disease (about 10-15% of children and adolescents suffer from SLE) and most often occurs in girls during adolescence [3], which is most likely due to hormonal changes during puberty. Patients of childhood and young age, as a rule, have more severe initial manifestations of the disease and a worse prognosis compared to adult patients [4, 5]. The risk of developing SLE as the child grows increases from 12 to 51 cases per 100,000 population. This is confirmed by data from Canadian scientists, according to which in the study group, about 3% of children developed SLE before the age of 6 years, 20% of patients with SLE - between the ages of 6 and 10 years, the share of children from 11 to 13 years and from 14 to 18 years accounted for 31 and 46%, respectively; of all observed patients, 80% of all children were girls [6]. SLE is extremely rare in children under 1 year of age: from 1975 to 2008. Only 15 such cases have been described, excluding neonatal systemic lupus erythematosus. Among the described patients, 7 girls (46.67%) and 8 boys (53.33%), ratio 1:1.14, aged from 1 to 11 months, while gastrointestinal tract lesions, expressed in stool disturbances, were observed in 3 patients, and blood in the stool was described in two [7, 8]. The clinical picture of SLE is dominated by symptoms of damage to the joints, cardiovascular system (pericarditis, myocarditis, endocarditis), kidneys (diffuse glomerulonephritis - lupus nephritis), and they are often so pronounced that gastroenterological symptoms fade into the background. This is confirmed by data from several multicenter studies. In a study that included children with SLE from 39 countries, in the group of patients with SDI≥1, kidney damage was observed in 32.6% of cases, nervous system damage and mental illness - in 26.9%, musculoskeletal system damage - in 26.9% of cases, skin involvement - in 19%, while gastrointestinal tract involvement - in 5.4% of cases [9]. Many studies of children and adults with SLE do not describe patients with gastrointestinal involvement. The most common manifestations of the disease were also: damage to the musculoskeletal system (48.1-77.7%), skin (31.1-88.8%), kidneys (27.9-67%), nervous system (17- 19.4%), hematological disorders (13.4-55.5%) [10-12]. SLE manifests itself in children most often with hematological disorders (72-73.4%), skin manifestations (70-76.3%), skeletal muscle lesions (31.7-64%), kidney lesions (50-86.2% ), fever (23.8-58%), neurological and mental disorders (20.8%) [13, 14]. The diagnostic criteria for SLE are presented in the table. Depending on the interests of researchers studying systemic lupus erythematosus, data on the frequency of gastrointestinal manifestations of this disease vary widely. Gastrointestinal manifestations in systemic lupus erythematosus, as a rule, are not specific, and usually the doctor decides whether they are part of the underlying disease or whether it is an intercurrent process. For example, the susceptibility of these patients to infections of all types is well known, so cases of frequent attacks of acute gastroenteritis of short duration can hardly be attributed to the manifestation of the underlying disease. With careful attention from the doctor, gastrointestinal symptoms can be detected in more than half of the patients, and in some of them these complaints were the first manifestation of the disease [15]. Thus, according to various authors, damage to the gastrointestinal tract in systemic lupus erythematosus in adults occurred in 8-40% of cases [14, 15], and in children in 2.2-19% [9, 18]. At the same time, the proportion of pediatric patients with manifestations of SLE in the form of gastrointestinal lesions was 19.8-32% [13, 14]. Some of the most common symptoms of gastrointestinal damage in SLE are diarrhea and gastrointestinal bleeding. According to various researchers, diarrhea is observed in 4-30.8% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus [18-23]. Most often, persistent diarrhea in combination with abdominal pain is associated with intestinal arteritis, accompanied by ulceration of the intestinal mucosa. In some cases, this symptom may be a manifestation of ulcerative colitis. There is information in the literature about the possibility of coexistence of these diseases [24-26]. A study of intestinal motility in patients with a combination of systemic lupus erythematosus and ulcerative colitis and in patients with ulcerative colitis does not reveal any differences. Most patients with lupus and ulcerative colitis also have liver damage. Gastrointestinal bleeding, manifested as melena or hematemesis, is observed in 5-10% of cases in patients with lupus [15, 18, 20-22]. This symptom is a consequence of peptic ulcerations of the stomach or intestinal hemorrhages. Morphological studies reveal arteritis with thrombosis of small vessels, leading to ulceration of the wall of the small intestine. The colon may also be involved in this process. In some cases, along with ulceration of the intestinal wall, perforation may also be observed. The cause of bleeding can also be thrombocytopenia, which is observed in some patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. In addition, the possibility of bleeding from steroid ulcers in lupus patients receiving steroid therapy should never be forgotten. A morphological study of the gastric mucosa in patients with lupus reveals signs of gastritis of varying severity in more than half of them. These changes are not specific and cannot be associated with drug therapy [27]. Small intestinal biopsy in selected patients reveals shortening and flattening of the villi, swelling and infiltration of the lamina propria of the intestinal mucosa [28, 29], as well as signs of vasculitis [29]. Child Dasha K., 3 years 8 months, was admitted to the Russian Children's Clinical Hospital; at the time of admission she had no complaints. From the medical history it is known that in the 1st year of life the girl had 2 episodes of loose stools: at 6 months and at 11 months; during the second episode, a small amount of blood was detected in the stool, for which she received symptomatic treatment. At the age of 1 year, examination in the hemogram revealed an increase in ESR to 17 mm/h, and at 1 year 7 months after suffering from acute respiratory viral infection, examination in the hemogram revealed an increase in ESR to 50 mm/h, a decrease in hemoglobin to 107 g/l, with According to her mother, the girl became lethargic, capricious, fatigue increased, and hoarseness appeared. In the 2nd year of life, the child continued to have mushy stools up to 4-5 times a day, for which the girl was repeatedly examined in the hospital at her place of residence, the following persisted: an increase in ESR - up to 29-34-52 mm/h, a decrease in hemoglobin - up to 99-101 g/l, thrombocytopenia - up to 170-190 thousand. At 3 years old, the girl was consulted by a gastroenterologist. Based on the examination, helminthic infestation was suspected and 2 courses of complex anthelmintic therapy were administered. However, after the second course of anthelmintic therapy, a daily increase in temperature to subfebrile levels and large quantities of mucus in the stool appeared; subsequently, the girl became more lethargic, capricious, her appetite sharply decreased, and febrile fever appeared. With these complaints, the child was hospitalized in the infectious diseases hospital (Vladivostok), where examination in the hemogram revealed a decrease in hemoglobin to 83 g/l, an increase in ESR to 62-67 mm/h, and an increase in CRP (++); in general urine analysis: minimal proteinuria, leukocyturia (5-6 per field of view), erythrocyturia (10-12 per field of view); Ultrasound of the abdominal organs reveals hepatomegaly. The girl received antibacterial therapy, against which the febrile fever persisted (38.5-39°C), and her health remained poor. In order to exclude oncohematological disease, the child was examined in the hematology department of the Vladivostok hospital (a bone marrow puncture was performed twice), where a serological study revealed antibodies to double-stranded DNA 4+, antibodies to histones 4+, nucleosomes 4+, antibodies to cardiolipin 60.8 (normal - For further examination with a referral diagnosis of “Connective tissue disease (SLE?): tubulointerstitial nephritis, moderate secondary anemia, secondary thrombocytopenia" she was transferred to the cardiology department of the Vladivostok hospital. Complaints of abdominal pain, veins persisted blood and mucus in the stool, there was an increase in body temperature to subfebrile values. The child underwent a colonoscopy and was diagnosed with erosive proctosigmoditis. Histological examination gave the following conclusion: “changes pathognomonic for SLE, UC, helminthic infestation were not detected in the biopsy specimens.” According to Ultrasound - hepatosplenomegaly. In the hemogram: hemoglobin - 91-100 g/l, platelets - 290 thousand, serological examination revealed signs of nonspecific inflammation: increased titers of CRP, seromucoid, increased ESR to 54 mm/h, serum levels of Ig G, M, And they were within normal limits. The child was prescribed dexamethasone at a dose of 8 mg/day, followed by a transfer to metipred at a dose of 4 mg/day. With this therapy, the child’s general well-being improved, body temperature and stool normalized, and the size of the liver and spleen decreased. At the time of admission to the Russian Children's Clinical Hospital at the age of 3 years 8 months, the child's condition was satisfactory and she had no active complaints. After an attempt was made to reduce the dose of methylpred until it was completely discontinued, an increase in temperature to febrile values and the appearance of watery stool mixed with mucus were noted, and therefore the dose of methylpred was gradually increased to 12 mg/day (1 mg/kg/day). During the examination, anemia was noted (hemoglobin 86-109 g/l), a tendency towards leukopenia (5.2-11.0¥109/l) against the background of an increase in ESR (32-58 mm/h), in a biochemical blood test: hypergammaglobulinemia – 18.1 g/l (normal: 8.4-18.0), increased cholesterol levels to 6.8 mmol/l (normal: 2.00-5.00 mmol/l) and triglycerides to 3.75 mmol /l (normal – 0.45-1.82 mmol/l), the immunogram revealed an increase in the levels of IgG, IgM, IgA approximately one and a half times compared to the norm, hypocomplementemia: C3 – 50.0 mg/dl (normal – 79.0-152) and C4 - 1.91 mg/dl (normal - 16.0-38.0), increased titers of antibodies to ds-DNA remained - 27 U/ml (normal The child received infusion therapy using crystalloid and colloidal solutions (Refortan® HES 200/0.5, Berlin-Chemie AG, Germany) Refortan® colloidal plasma-substituting solution of hydroxyethylated corn starch is used to correct hypovolemia, hemorheological disorders and colloid-osmotic insufficiency in conditions of endothelial damage. According to research results, Refortan® HES 200/0.5 meets the requirements for an “ideal plasma substitute” - it quickly restores the reduced volume of circulating blood; restores hemodynamic balance; normalizes microcirculation; has a long-lasting intravascular effect; improves the rheological properties of blood; improves the delivery of oxygen and other components, as well as tissue metabolism and organ functioning; easily metabolized, easily excreted from the body and well tolerated; has minimal impact on the immune system. Transfusion of the Refortan® HES 200/0.5 solution does not cause an increase in the level of histamine in the blood serum, and no immunological reactions of the antigen-antibody type characteristic of dextran solutions were detected. In addition, Refortan® has properties not found in other colloidal plasma replacement drugs [31, 32]: • prevents the development of capillary hyperpermeability syndrome by closing pores in the endothelium; • modulates the action of adhesion molecules and inflammatory mediators, which, circulating in the blood during critical conditions, increase secondary tissue damage by binding to neutrophils and endothelial cells; • does not cause activation of the complement system associated with generalized inflammatory processes that disrupt the functions of many internal organs. In conditions of ischemic-reperture damage, the solutions of the GEC reduce the degree of damage to the lungs and other organs. Therapy was also continued with the therapy of a meta -chapter at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day (12 mg/day) with the addition of sulfasalazine at a dose of 750 mg/day (within 12 days), and subsequently - prednisolone at a dose of 25 mg/1 mg/1 mg/ kg). Against the background of therapy, prednisolone noted a positive dynamics in the form of a decrease in proteinuria to 1.35 g/day. The girl was discharged with recommendations to reduce the dose of prednisone and strengthen immunosuppressive therapy with the addition of mycophenolate of Moopherines, however, these recommendations were not completed and only a reduction in the dose of predisolone was carried out. And at a dose of 2.5 mg/day, the appearance of urinary syndrome (PU) with high immunological activity (AT to DNA) was again noted, due to the increase in activity, the dose of prednisolone was increased to 5 mg/day, and a course of treatment with a rituximab was also carried out In a dose of 375 mg/m2/week No. 5. After that, the girl was discharged from the RDKB with an improvement: antibodies to DSDNK - 9.5 units/ml (at normal - up to 25 units/ml), antibodies to cardiolipin - IgA - 0.686 units/ml (norm - diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus for this The child is confirmed by the data of the morphological study of the kidney and the presence of antibodies to the DSDNK as a specific marker of the SLE. The uniqueness of this clinical case lies in an early debut (at the age of 6 months) and that the disease made its debut with damage to the gastrointestinal tract in the form of colitis, with which it was It is due to the fact that it was originally regarded as non-specific ulcerative colitis. In addition, data is presented in the literature, according to which, in patients with nyak, antibodies to DSDNK can detect [30]. Despite the fact that Lupus-nefrit was diagnosed, the child was interpreted for a long time As having 2 nosology. Given the negative dynamics from the Nyak, with the periodic activity of the Lupus-nefritis, it was decided that these are not two diseases, but the SLE, which debuted from the lesion of the gastrointestinal tract. Based on the table, the child corresponded to 6 diagnostic criteria for SLE. Thus, in this group of patients, it is correct to use several groups of drugs: met prophet, sulfasalazine and for the treatment of moderate blood loss - reform®, which has a pronounced hemodynamic effect and use of use.

References 1. Arvola T., Ruuska T., Keränen J., Hyöty H., Salminen S., Isolauri E. Rectal Bleeding in Infancy: Clinical, Allergological, and Microbiological Examination. Pediatrics. 2006; 117: e760-e768. 2. Buller H., Chin S., Kirschner B., Kohn J., Markowitz J., Moore D., Murch S., Taminiau J. Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents: Working Group Report of the First World Congress of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2002; 35: 151-158. 3. Stichweh D., Arce E., Pascual V. Update on pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004; 16: 577-87. 4. Tucker LB, Menon S., Schaller JG, Isenberg DA Adult- and childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of onset, clinical features, serology, and outcome. Br J Rheumatol. 1995 Sep; 34 (9): 866-72. 5. Rood MJ, ten Cate R, van Suijlekom-Smit LW et al. Childhood-onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: clinical presentation and prognosis in 31 patients. Scand J Rheumatol. 1999; 28 (4): 222-6. 6. Marks SD, Hiraki L., Hagelberg S., Silverman ED, Hebert D. Age-related renal prognosis of childhood-onset SLE. Pediatr Nephrol. 2002; 17 (9): 107. 7. Dale RC, Tang SP, Heckmatt JZ, Tatnall FM Familial systemic lupus erythematosus and congenital infection-like syndrome. Neuropediatrics. 2000 Jun; 31 (3): 155-8. 8. Zulian F., Pluchinotta F., Martini G., Da Dalt L., Zacchello G. Severe clinical course of systemic lupus erythematosus in the first year of life. Lupus. 2008 Sep; 17 (9):780-6. 9. Gutiérrez-Suárez R., Ruperto N., Gastaldi R. et al. A proposal for a pediatric version of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index based on the analysis of 1,015 patients with juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Sep; 54 (9): 2989-96. 10. Jacobsen S., Petersen J., Ullman S. et al. A multicentre study of 513 Danish patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. II. Disease mortality and clinical factors of prognostic value. Clin Rheumatol. 1998; 17 (6): 478-84. 11. Cervera R., Khamashta MA, Font J. et al. Morbidity and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus during a 10-year period: a comparison of early and late manifestations in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003 Sep; 82 (5): 299-308. 12. Moradinejad MH, Zamani GR, Kiani AR, Esfahani T. Clinical features of juvenile lupus erythematosus in Iranian children. Acta Reumatol Port. 2008 Jan-Mar; 33 (1): 63-7. 13. Bader-Meunier B., Armengaud JB, Haddad E. et al. Initial presentation of childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a French multicenter study. J Pediatr. May 2005; 146 (5): 648-53. 14. Supavekin S., Chatchomchuan W., Pattaragarn A., Suntornpoch V., Sumboonnanonda A. Pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus in Siriraj Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005 Nov; 88 Suppl 8: S115-23. 15. Dubois EL, Tuffanelli DL Clinical manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Computer analysis of 520 cases. JAMA. 1964 Oct 12; 190: 104-11. 16. Hallegua DS, Wallace DJ Gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000; 12: 379-85. 17. Sultan SM, Ioannou Y., Isenberg DA A review of gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology. 1999; 38: 917-32. 18. Richer O., Ulinski T., Lemelle I. et al. Abdominal manifestations in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. Feb 2007; 66 (2): 174-8. 19. Jessar R., Lamont-Havers R., Ragar C. Natural history of lupus erythematosus disseminatus. Ann. Intern. Med. 1953; 38: 717-29. 20. Harvey AM, Shulman LE, Tumulty PA, Conley CL, Schoenrich EH Systemic lupus erythematosus: review of the literature and clinical analysis of 138 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1954 Dec; 33 (4): 291-437. 21. Dubois EL, Wierzchowiecki M, Cox MB, Weiner JM Duration and death in systemic lupus erythematosus. An analysis of 249 cases. JAMA. 1974 Mar 25; 227 (12): 1399-402. 22. Fries J., Holman HR Systemic lupus erythematosus: a clinical analysis. Philadelphia: WB Saundres, 1975. 23. Xu D, Yang H, Lai CC et. al. Clinical analysis of systemic lupus erythematosus with gastrointestinal manifestations. Lupus. 2010 Apr 21. . 24. Brown CH, Haserick JR, Shirey EK Chronic ulcerative colitis with systemic lupus erythematosus; report of a case. Cleve Clin Q. 1956 Jan; 23 (1): 43-6. 25. Kurlander DJ, Kirsner JB The association of chronic “nonspecific” inflammatory bowel disease with lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med. 1964 May; 60: 799-813. 26. Stevens HP, Ostlere LS, Rustin MH Systemic lupus erythematosus in association with ulcerative colitis: related autoimmune diseases. Br J Dermatol. Mar 1994; 130 (3): 385-9. 27. Siurala M., Julkunen H., Toivonen S., Pelkonen R., Saxen E., Pitkaenen E. Digestive tract in collagen diseases. Acta Med Scand. July 1965; 178: 13-25. 28. Bazinet P., Marin G. A. Malabsorption in systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Dig Dis. May 1971; 16 (5): 460-6. 29. Nadorra RL, Nakazato Y., Landing BH Pathological features of gastrointestinal tract lesions in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: study of 26 patients, with review of the literature. Pediatr Pathol. 1987; 7 (3): 245-59. 30. Dalekos GN, Manoussakis MN, Goussia AC, Tsianos EV, Moutsopoulos HM Soluble interleukin-2 receptors, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and other autoantibodies in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. May 1993; 34 (5): 658-64. 31. Molchanov I.V., Goldina O.A., Gorbachevsky Yu.V. Hydroxyethyl starch solutions are modern and effective plasma replacement agents for infusion therapy. M.: NTsSSKh, 1998; 138. 32. Webb AR, Moss RF, Tighe D. A narrow range, medium molecular weight pentastarch reduces structural organ damage in model of sepsis. Int Care Med. 1992; 18: 348-55.

Causes of anal fissure

The pathogenetic basis for the development of anal fissure in children is a violation of the integrity of the anal mucosa. The cause of such a defect may be:

- Tear of tissue due to the passage of too thick stool.

- Incorrect placement of cleansing enemas or gas exhaust tubes when the mucous membrane is injured by hard elements of medical products.

- Incorrectly performed surgical interventions in the anorectal area.

It is important to understand that a violation of the integrity of the mucous membrane in the described situations does not always occur. The risk of developing the problem is increased by provoking factors:

- Genetic predisposition or the presence of congenital malformations of the anorectal region or the entire gastrointestinal tract (GIT).

- Chronic intestinal infections accompanied by diarrhea. In such cases, the mucous membrane becomes thinner and becomes more vulnerable to the mechanical impact of thick feces.

The situation is further aggravated by the presence of a local inflammatory process.

- Proctitis and other diseases of the rectum, which directly reduce tissue resistance.

- Metabolic disorders. Diabetes mellitus and pathology of absorption of individual food components create conditions for defecation disorders and changes in the normal architecture of tissues.

- Traumatic injuries to the anorectal area - falls, blows, scratching of the anal area against the background of helminthic infestation.