Hypertensive crisis is a sharp rise in blood pressure (BP), accompanied by symptoms of cerebrovascular accident, left ventricular failure, and autonomic reactions. The causes of hypertensive crises in children are usually secondary (symptomatic) arterial hypertension.

Clinical manifestations:

1. A sharp piercing headache of frontal or occipital localization lasting several hours/day.

2. Pronounced vegetative manifestations:

- nausea, vomiting;

- abdominal pain;

- sweating;

- paleness or hyperemia of the face.

3. Symptoms of cerebrovascular accident: ringing in the ears, dizziness, darkening of the eyes, spots before the eyes, tremors of the hands, convulsions.

4. Shortness of breath as a manifestation of left ventricular failure; tense and rapid pulse.

5. Blood pressure reaches high numbers (160–180/90–110 mm Hg).

Tactically, there are two levels of hypertension in children: from the 95th to the 99th age centile (does not require emergency treatment, only routine examination and treatment) and above the 99th centile (needs emergency blood pressure correction). Age indicators of significant (severe) arterial hypertension (BP levels above the 99th centile), requiring immediate reduction in blood pressure, are given in Table. 1.

Antihypertensive drugs should also be used in cases where the child develops threatening symptoms: headache, repeated vomiting, disorientation, convulsions, cardiac dysfunction.

The main goal of stopping a hypertensive crisis is a controlled reduction in blood pressure to a safe level to prevent complications. Due to the risk of severe arterial hypotension, it is not recommended to rapidly reduce blood pressure. A rapid drop in blood pressure can cause a decrease in blood supply to the brain, especially in situations where pulse blood supply was low, and lead to the development of cerebral ischemia and even cerebral infarction. Typically, a decrease in blood pressure to a normal level (below the 95th centile for a given gender, age and height) is carried out in stages: in the first 6–12 hours, blood pressure is reduced by 1/3 of the planned decrease; during the first day, blood pressure is reduced by another 1/3; over the next 2–4 days, complete normalization of blood pressure is achieved.

To relieve a hypertensive crisis it is necessary:

- creating the most relaxed environment possible;

- use of antihypertensive drugs;

- sedative therapy.

There are a number of therapeutic techniques for relieving emergencies associated with arterial hypertension. The choice of treatment methods depends on the clinical situation and the experience of the doctor. The classification given below (according to D. Lawrence, P. Bennit, 1991) helps to navigate the variety of medications used for arterial hypertension.

Vasodilators

Hydralazine is a direct-acting vasodilator, most effective when administered intravenously, and an immediate effect is achieved; when administered intramuscularly, the effect occurs within 15–30 minutes. The drug does not affect renal blood flow and rarely leads to orthostatic hypotension. Used at an initial dose of 0.15–0.2 mg/kg intravenously. If there is no effect, the dose may be increased every 6 hours to a maximum of 1.5 mg/kg. Hydralazine is most effective in combination with diuretics or other antihypertensive drugs for intravenous administration. Main side effects: tachycardia, nausea, vomiting, headache, diarrhea. Positive tests for LE cells and rheumatoid factor are very rare in children. The drug is not used for arrhythmias and heart failure. Efficiency is inconsistent.

Sodium nitroprusside is an arteriolar and venous dilator. It increases renal blood flow with minimal effect on cardiac output and controls blood pressure when administered intravenously. The drug acts quickly and is effective even in cases where other means are unsuccessful. By adjusting the infusion rate, the desired blood pressure can be achieved. Administered as an intravenous infusion with constant monitoring in the intensive care unit. The prepared solution is inactivated by light. Along with nitroprusside, other drugs cannot be administered through the same venous catheter. The initial dose in children and adolescents is 0.5–1 mcg/kg/min with a subsequent dose increase to 8 mcg/kg/min. Monitoring the level of thiocyanate in the blood is required, since nitroprusside is converted to thiocyanate in the liver by thiosulfate sulfide transferase. In case of liver failure, the drug is used with caution. Constant monitoring in the intensive care unit is required. At the end of the infusion, the effect of the drug ceases immediately. With prolonged use (> 24 hours), metabolic acidosis may occur.

Diazoxide is a second-line drug for rapidly lowering blood pressure. It belongs to the benzothiazides, has no diuretic effect and acts directly on the smooth muscles of blood vessels, reducing muscle tone; does not reduce renal blood flow. It is administered only intravenously at a dose of 1 mg/kg in a rapid stream, which allows achieving the greatest vasodilation with minimal binding to blood proteins. The effect lasts 3–15 hours. If the initial dose is not enough to achieve an effect, the administration is repeated at intervals of 15–20 minutes (maximum dose - 5 mg/kg). The disadvantage is the inability to regulate the decrease in blood pressure. Side effects: hyperglycemia, sodium and water retention; Transient tachycardia often occurs.

Differentiated approach to the treatment of hypertensive crises

Recent years have been marked by a revision of traditional therapeutic approaches to many pathological conditions. This is due to the emergence of new information about the mechanisms of disease development, original medicines, and the conduct of clinical studies based on the principles of “evidence-based” medicine. The changes have affected many branches of medicine, including emergency conditions.

Hypertensive crisis (HC) is one of the most common and prognostically dangerous syndromes in emergency cardiology. According to the National Scientific and Practical Society of Emergency Medical Care, more than 20,000 emergency medical care (EMS) calls are made daily in the Russian Federation regarding GC [3]. Clinical and statistical analysis of calls from emergency medical services teams for 2005–2009. showed that the increase in the frequency of hypertensive crises in Moscow exceeded 14%. At the same time, an increase in the number of GCs was revealed among young people (18–35 years) [1]. According to Marik R.E., 2011 [19], GCs are found in 2% of patients with arterial hypertension. It can be noted that, despite the progress achieved in the treatment of arterial hypertension, the frequency of GC is not decreasing.

Reasons contributing to the occurrence of hypertensive crisis:

1) lack of constant drug monitoring of blood pressure levels; 2) use of insufficient doses of antihypertensive drugs; 3) the use of monotherapy in cases where combination therapy is indicated; 4) use of irrational combinations of drugs; 5) lack of influence on risk factors.

According to S.A. Shalnova, the number of patients in whom antihypertensive therapy can be considered effective is no more than 15% of the total number of patients suffering from hypertension [8].

The development of a hypertensive crisis is associated with a worsening prognosis of patients with hypertension. According to a number of authors, in the absence of treatment, most patients die within 6 months due to progressive malignant hypertension. Survival without therapy at 1 year ranged from 10 to 20%. With therapy, the 5-year survival rate was more than 70% [13, 18, 22]. The results of the domestic retrospective multicenter study OSADA (Optimal reduction of blood pressure during uncomplicated hypertensive crises in patients with hypertension) showed a significant increase in the frequency and risk of cardiovascular complications (risk of non-fatal cerebral stroke/transient ischemic attacks, chronic heart failure, development of myocardial ischemia and left ventricular hypertrophy ) with uncomplicated GC [4]. The reasons for this are insufficient patient adherence to treatment, as well as the lack of adequate blood pressure control during the outpatient stage of therapy.

In accordance with the National Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension, prepared by RMOAG/VNOK, as well as JNC [5, 11], the following definition of crisis is adopted: hypertensive crisis is an acutely expressed increase in blood pressure, accompanied by clinical symptoms and requiring an immediate controlled decrease in blood pressure in order to preventing or limiting target organ damage.

Key points: 1) the absence of strict quantitative blood pressure parameters for diagnosing blood pressure when systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure are equivalent. The refusal of the quantitative criterion of blood pressure is due to the fact that the occurrence and severity of acute damage to target organs is determined not so much by the high absolute level of blood pressure, but by the degree of its relative increase in a given patient; 2) the range of symptoms of target organ damage is quite clearly defined and determines the tactics of patient management; 3) a controlled decrease in blood pressure is not necessary to normal values. The clinician’s task is a differentiated approach to lowering blood pressure depending on the specific clinical situation, taking into account the potential risk of hypotension and hypoperfusion of target organs with overly aggressive therapy. The clinical classification of hypertensive crises is presented in the form of two main positions [5, 6, 17]: I. Complicated hypertension, emergency hypertension, life-threatening hypertension (hypertensive emergensies).

Accompanied by the development of acute, clinically significant and potentially fatal damage to target organs. Emergency treatment is required by an increase in blood pressure that leads to the development of the following clinical situations: • acute hypertensive encephalopathy; • acute cerebrovascular accident; • acute coronary syndrome; • acute left ventricular failure; • dissecting aortic aneurysm; • eclampsia; • pheochromocytoma; • acute or rapidly progressive renal failure.

II. Uncomplicated hypertension, emergency hypertension, non-life-threatening (hypertensive urgencies). An asymptomatic increase in blood pressure to potentially dangerous levels in the absence of target organ damage.

To properly provide medical care for GC, it is necessary to: – assess the severity and severity of the clinical situation; – determine the main causes and mechanisms of increased blood pressure; – determine the level to which it is necessary to reduce blood pressure and the time during which this must be done; – select the main drugs for antihypertensive therapy and the method of their use.

Differentiated approach in the treatment of GC

I. Complicated HA Strategy: lowering blood pressure to prevent progression of the clinical situation and damage to target organs. Tactical measures: – hospitalization in a specialized department; – immediate reduction in blood pressure* by 15–20% of the initial value during the first 30–120 minutes, but not lower than 160/100 mm Hg. Art. Further, within 2–6 hours the blood pressure level is 160/100 mm Hg. Art.* – the parenteral route of drug administration is justified.

*except for acute cerebrovascular accident, dissection of aortic aneurysm.

II. Uncomplicated GC Strategy: lowering blood pressure to prevent the occurrence of a clinical situation and target organ damage. – in most cases, hospitalization is not required; – a gradual decrease in blood pressure by 15–20% of the pressure level in a crisis. GK control horizon – 12–24 hours; – oral route of drug administration.

Treatment tactics for complicated GC

Acute hypertensive encephalopathy is the result of brain hyperperfusion with exhausted autoregulation capabilities. A significant increase in blood pressure leads to failure of the mechanisms of autoregulation of cerebral blood flow, increased intracranial pressure with the development of cerebral edema, accompanied by general cerebral and focal symptoms.

The main distinguishing symptom is a typical headache: initially localized in the occipital region, then becomes diffuse, intensifies in situations that impede the outflow of blood from the veins of the head (horizontal position, straining, coughing), decreases (in the early stages of development) with a vertical position of the body; the diagnosis of a crisis requiring emergency care is established from the moment the occipital pain irradiates into the retro-orbital spaces; in the late phase of the crisis, yawning, nausea, and bouts of vomiting appear, which briefly alleviate the patient’s well-being; in the absence of adequate therapy, there is a disorder of consciousness (confusion, stunnedness), convulsions, visual impairment up to blindness.

The increase in symptoms is gradual, over 48–72 hours. All of the listed pathological changes characteristic of hypertensive encephalopathy are potentially completely reversible and resolve as blood pressure gradually decreases. The lack of adequate therapy leads to failure of autoregulation of cerebral blood flow with aggravation or occurrence of ischemia.

Acute ischemic cerebrovascular accident

The tactics of managing patients with hypertensive crisis and acute cerebrovascular accident has fundamental features.

Concerns about worsening hypoperfusion and expansion of the cerebral infarction zone with a decrease in pressure in such a situation are justified. Unfortunately, at the moment there are no evidence-based medicine data regarding tactics for controlling blood pressure in patients with a clinical picture of stroke during GC. Today, the most common approach involves a careful, slow reduction in blood pressure only in cases of excessive increase.

General tactics for lowering blood pressure in patients with acute hypertensive encephalopathy and acute ischemic cerebrovascular accident [7]:

– reduction in blood pressure by no more than 10–15% of the level of average blood pressure (BPav) and in no less than 2–3 hours (BPav = [SBP-DBP] / 3 + DBP, norm 60–130 mm Hg. Art.) *; – decrease in blood pressure only in cases of excessive increase (SBP more than 220 mm Hg, DBP more than 110±10 mm Hg); – with blood pressure less than 185/110 mm Hg. Art. – observation; – fast-acting and “short-lived” drugs; – comparison of the results of antihypertensive therapy with the dynamics of the clinical picture; – a clinical situation requiring the presence of a neurologist.

*SBP is systolic blood pressure, DBP is diastolic blood pressure. Acute cerebrovascular accident of hemorrhagic type

A spontaneous decrease in blood pressure often does not occur in the coming days. There is a danger of both increased blood pressure (continuation of bleeding) and its decrease (deterioration of collateral blood flow).

There is no consensus on the advisability of lowering blood pressure. An angiogram of the cerebral vessels often indicates severe spasm, depending on the location of the hemorrhage, and it is believed that a further decrease in blood pressure jeopardizes the circulation in the ischemic zone, possibly leading to infarction in this zone. On the one hand, the risk of recurrent subarachnoid hemorrhage increases with high blood pressure, on the other hand, the effectiveness of therapy is problematic. Features of blood pressure reduction in patients with acute hemorrhagic cerebrovascular accident [20]:

– antihypertensive therapy is not recommended for blood pressure below 180/105 mm Hg. Art. and blood pressure lower than 130 mm Hg. Art.; – with blood pressure more than 180/105 mm Hg. Art. and blood pressure above 130 mm Hg. Art. and if there are signs of increased intracranial pressure, therapy is indicated (parenteral administration of drugs according to the clinical situation); – with blood pressure more than 180/105 mm Hg. Art. and blood pressure above 130 mm Hg. Art. and there are no signs of increased intracranial pressure, therapy (parenteral administration of drugs) is indicated until blood pressure reaches 160/90 mm Hg. Art. and blood pressure 110 mm Hg. Art. monitoring the patient’s condition every 15 minutes; – drugs are fast-acting and short-lived.

Acute coronary syndrome

High afterload requires antihypertensive therapy, as it aggravates myocardial ischemia. However, in acute myocardial ischemia, excessively aggressive antihypertensive therapy can be dangerous. The hypertrophied left ventricle is extremely sensitive to hypotension. The subendocardium is most vulnerable to a decrease in perfusion pressure, which is probably due to the greater pressure on the endocardial vessels during systole. With a sharp decrease in systemic blood pressure with a corresponding decrease in coronary blood flow, autoregulation is first depleted in the subendocardium and then in the subepicardium.

On the other hand, in the case of acute coronary syndrome with ST elevation and a pronounced increase in blood pressure, the main goal is to reduce blood pressure as quickly as possible to levels considered safe for thrombolysis (up to 160/100 mm Hg). A relative contraindication to thrombolysis is uncontrolled hypertension with SBP values > 180 mm Hg. Art. Acute left ventricular failure

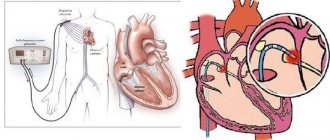

Requires rapid reduction of blood pressure by parenteral administration of drugs. In this case, antihypertensive therapy becomes a component of the treatment of acute left ventricular failure. Lowering blood pressure significantly reduces the workload on the weakened left ventricle.

Acute dissection of aortic aneurysm

The main symptom of aortic dissection is sudden, severe and prolonged pain in the chest, radiating to the neck, between the shoulder blades, and to the lower back. Pain is accompanied by fear of death. Headache, dizziness, loss of consciousness, nausea, vomiting, and shortness of breath may occur. In half of the patients, a difference in blood pressure in the arms is detected; in 60% of patients, a diastolic murmur appears in the aorta.

Tactics for aortic aneurysm dissection [7]:

– reduction in blood pressure by 25–30% for 5–10 minutes, followed by its reduction to the maximum tolerated level; – target SBP <110 mmHg. Art.; – the clinical situation requires the participation of an angiosurgeon.

Table 1 presents drugs for the relief of complicated GC [5, 7, 21].

Nitrates moderately and controllably lower blood pressure, reduce preload and improve blood supply to the heart muscle. Being venous vasodilators, nitrates, when titrated slowly, cause dilatation of arterioles, including in the coronary vascular system. At the same time, the vessels of the ischemic area also dilate and, thus, the phenomenon of stealing is eliminated.

β-blockers are among the drugs absolutely indicated for lowering blood pressure in acute coronary syndrome. Their effect is due to a decrease in myocardial oxygen consumption (by 15–30%) due to a decrease in blood pressure, heart rate and cardiac output. In addition, β-blockers promote the redistribution of blood in the myocardium in favor of ischemic areas and have an antiarrhythmic effect.

The use of ACE inhibitors, which reduce the peripheral vascular resistance without reflex activation of the sympathoadrenal system, is effective. Drugs of this class also have an anti-ischemic effect due to a decrease in oxygen demand due to a decrease in afterload and an improvement in coronary blood flow as a result of a decrease in left ventricular wall tension.

The use of short-acting nifedipine, in addition to possible hypotension, is accompanied by a reflex increase in heart rate and an increase in myocardial oxygen demand. In addition, nifedipine causes preferential vasodilation of non-ischemic areas of the myocardium (steal phenomenon). These undesirable effects do not apply to verapamil, diltiazem, amlodipine and other drugs of the second and third generations of dihydropyridines (long-acting).

Sodium nitroprusside and dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are contraindicated as monotherapy because they increase pulse pressure and heart rate. It is possible to use them in combination with β-blockers (the administration of the latter should begin before the administration of vasodilators). If there are contraindications to the use of β-blockers, verapamil (isoptin) is used.

From a practical point of view, the difficulty of treating GC is that not all drugs are available for use in Russia (sodium nitroprusside, labetalol). At the same time, the need for effective and safe drugs that could be used in patients with GC is undeniable.

The most promising drugs are those that affect different mechanisms of action. These drugs include the alpha 1 adrenergic blocker urapidil, available in our country.

Urapidil has a combined effect, as a result of which it reduces preload (reduces pressure in the pulmonary capillaries and pulmonary artery) and afterload (reduces total peripheral vascular resistance) on the myocardium. Urapidil reduces the overall resistance in the vessels of the kidneys and improves blood circulation in the kidneys without increasing intracranial pressure. The ability of urapidil to reduce vascular resistance in the pulmonary circulation and reduce high blood pressure makes the use of this drug relevant in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [9].

The drug is contraindicated for use under the age of 18 years, during pregnancy and lactation, since the effectiveness and safety of its use during these periods have not been established [2, 12].

Treatment tactics for uncomplicated GC

Uncomplicated HA is manifested by an oligosymptomatic increase in blood pressure in the absence of target organ damage.

For the treatment of uncomplicated hypertension, it is recommended to use oral antihypertensive drugs that provide a gradual decrease in blood pressure over several hours (up to a day). In the future, the achieved effect can be prolonged by switching to the planned use of antihypertensive drugs.

The main drugs of choice for lowering blood pressure in uncomplicated hypertensive crisis are presented in Table 2.

Alcohol-induced GCs

Hypertensive crises in people who abuse alcohol are not uncommon. A sharp increase in blood pressure is possible both in the phase of intoxication (intoxication) and in the abstinence phase. It is most often observed in the abstinence phase. Before starting antihypertensive therapy, it is advisable to perform rehydration to restore the patient's volume status.

β-blockers can be used to relieve a hypertensive crisis, since alcohol-induced GCs are based on stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system. It is possible to prescribe ACE inhibitors.

Avoid:

direct vasodilators - can increase the tachycardia characteristic of withdrawal; diuretics - there is a danger of worsening intoxication and hypovolemia; clonidine – potentiates the effect of alcohol.

Hypertensive crises in elderly patients

In elderly patients, the development of hypotension with potential hypoperfusion of organs, primarily the brain, heart, and kidneys, is especially dangerous. As a result of involution of the elastic structures of the vascular wall, atherosclerotic damage to the arteries and impaired myocardial function in elderly patients, cerebral, coronary and renal blood flow is reduced.

The main drug for stopping a crisis is clonidine per os, which provides a smooth and sustainable decrease in blood pressure. The second drug is nifedipine with prolonged release of the active substance per os. Not recommended: nifedipine in conventional forms with rapid release of the active substance, hydralazine, enalaprilat.

When providing emergency care, the correct choice of drugs for antihypertensive therapy is important. It is known that the level of blood pressure depends on the volume of circulating blood, myocardial contractility, and general peripheral vascular resistance. Therefore, emergency antihypertensive therapy should be aimed at all three of these mechanisms of blood pressure regulation, with an emphasis on the leading cause of its increase, taking into account the underlying and concomitant diseases, previous therapy and response to the use of antihypertensive drugs in the past.

Literature

1. Gaponova N.I., Plavunov N.F., Baratashvili V.L. [and others] Clinical and statistical analysis of arterial hypertension complicated by hypertensive crisis in Moscow for 2005–2009. // Cardiology. 2011. No. 2. pp. 40–44. 2. Gaponova N.I., Abdrakhmanov V.R., Tereshchenko S.N. Urapidil in the treatment of emergency conditions caused by increased blood pressure // Rational Pharmacotherapy in Cardiology. 2012. No. 8(5). pp. 703–707. 3. Hypertensive crisis at the prehospital stage. National Scientific and Practical Society of Emergency Medical Services. Practical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and prevention for primary care physicians. 2009. 4. Kolos I.P., Chazova I.E., Tereshchenko S.N. [etc.] Risk of developing cardiovascular complications in patients with frequent hypertensive crises. Preliminary results of a multicenter retrospective case-control study OSADA // Therapeutic archive. 2009. No. 9. pp. 9–12. 5. National recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension RMOAG/VNOK // Cardiovascular therapy and prevention. 2008. No. 7(6). Adj. 2. 6. Tereshchenko S.N. Hypertensive crises: diagnosis and treatment // Chazov E.I., Chazova I.E. Guide to arterial hypertension. M., 2005. pp. 676–689. 7. Tereshchenko S.N., Plavunov N.F. Hypertensive crises. M.: MEDpress-inform, 2011. 8. Shalnova S.A. Problems of treatment of arterial hypertension // Cardiovascular therapy and prevention. 2003. No. 2(3). pp. 17–21. 9. Adnot S., Anddrivet P., Piquet J. et al. The effects of urapidil therapy on hemodynamics and gas exchange in exercising patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pulmonary hypertension // Am. Rev. Respira. Dis. 1988. No. 137(5). R. 1068–1074. 10. Arima H, Anderson CS, Wang JG et al. Intensive Blood Pressure Reduction in Acute Cerebral Haemorrhage Trial Investigators. Lower treatment blood pressure is associated with greatest reduction in hematoma growth after acute intracerebral hemorrhage // Hypertension. 2010. No. 56(5). R. 852–858. 11. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR et al. JNC 7: Complete Report Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee Hypertension. 2003. No. 42. R. 1206–1252. 12. Dolley M., Goa KL Urapidil. A reappraisal of its use in the management of hypertension // Drugs. 1998. No. 56(5). R. 529–559. 13. Dustan HP, Schneckloth RE, Corcoran AC. et al. The effectiveness of long-term treatment of hypertension // Circulation. 1958. No. 18. R. 644–651. 14. European Stroke Organization (ESO) Executive Committee and the ESO Writing Committee. Guidelines for Management of Ischemic Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack 2008 // Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2008. No. 25. R. 457–507. 15. Gillis RA, Dretchen KL, Namath I. et al. Hypotensive effect of urapidil: CNS site and relative contribution // J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1987. No. 9. R. 103–109. 16. Hirschl MM, Seidler D, Müllner M et al. Efficacy of different antihypertensive drugs in the emergency department // J. Hum. Hypertens. 1996. Vol. 10 (suppl. 3): P. 143¬146. 17. Kaplan`s clinical hypertension. 9th ed. 2006, pp. 311–324. 18. Lip GYH, Beevers M., Beevers DG Do patients with de novo hypertension differ from patients with previously know hypertension when malignant phase hypertension occurs? //Am. J. Hypertens. 2000. No. 13. R. 934–939. 19. Marika PE, Rivera R. Hypertensive emergencies: an update // Curr. Opin. Crit. Care. 2011. No. 17. R. 569–580. 20. McKinnon M., O'Neill JM Hypertension In The Emergency Department: Treat Now, Later, Or Not At All // Emergency Medicine Practice. 2010. Jun. Vol. 12(6). 21. Varon J. Treatment of Acute Severe Hypertension Current and Newer Agents // Drugs. 2008. No. 68(3). R. 283–297. 22. Webster J, Petrie JC, Jeffers TA et al. Accelerated hypertension – patterns of mortality and clinical factors affecting outcome in patients // QJM. 1993. No. 86. R. 485–493.

Alpha blockers

Prazosin is a selective alpha-1 adrenergic blocker. It is characterized by a relatively short antihypertensive effect. Rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract (half-life - 2-4 hours). When taking the first dose of the drug, the most pronounced therapeutic effect is observed, orthostatic dysregulation is possible. Therefore, after taking the drug, the patient should be in a horizontal position. The initial dose is 0.5 mg.

Phentolamine is a non-selective alpha-blocker that causes short-term and reversible blockade of both postsynaptic alpha-1-adrenergic receptors and alpha-2-adrenergic receptors. Phentolamine is an effective antihypertensive drug with short-term action. The drug is used to treat hypertensive crisis in pheochromocytoma. Side effects are associated with blockade of alpha-2 adrenergic receptors (palpitations, sinus tachycardia, tachyarrhythmia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, etc.). Phentolamine is administered intravenously by drip or slow stream in 20 ml of saline sodium chloride solution (2 mg, but not more than 10 mg, every 5 minutes) until blood pressure normalizes.

Beta blockers

These drugs are used to eliminate excessive sympathotonic effects in cases where an increase in blood pressure is accompanied by pronounced tachycardia and heart rhythm disturbances. Preference should be given to selective beta-1 blockers.

Propranolol is a non-selective beta-blocker and is recommended to be taken orally. The usual dose for IV administration is 0.5–1 mg with close monitoring. IV propranolol is a backup treatment in life-threatening situations.

Atenolol is used at a dose of 0.7 mg/kg body weight. In more severe cases, when atenolol is ineffective, intravenous infusions of esmolol are used.

Esmolol is an ultra-short-acting selective beta-1 adrenergic blocker (about 9 minutes) and does not have intrinsic sympathomimetic or membrane-stabilizing activity. The hypotensive effect of the drug is due to negative chrono- and inotropic effects, a decrease in cardiac output and total peripheral resistance. When administered intravenously, the effect occurs within 5 minutes. During the first minute, the drug is administered at an initial dose of 500–600 mcg/kg. If there is no effect, the dose may be increased by 50 mcg/kg/min every 5–10 minutes, up to a maximum of 200 mcg/kg/min. Side effects: hypotension, bradycardia, decreased myocardial contractile function, acute pulmonary edema. There is little experience using it in children.

Labetalol is a selective alpha and non-selective beta blocker.

The initial dose is 0.25 mg/kg IV, then increased by 0.5 mg/kg every 15 minutes to a total dose of 1.25 mg/kg. The drug can also be administered as an intravenous infusion at a rate of 1–3 mg/kg/hour. Unlike other vasodilators, it does not cause reflex tachycardia. The dose does not depend on renal function. Unlike other beta-blockers, it does not affect glucose metabolism. It acts quickly (within 30 minutes), half-life is 5–8 hours. After normalization of blood pressure, the drug is taken orally. With both short-term and long-term therapy, in rare cases, liver damage is observed (usually reversible, but necrosis is also possible). It is necessary to monitor biochemical indicators of liver function and immediately discontinue labetalol if they change.

Calcium channel blockers

Nifedipine is an effective drug for relieving hypertensive crises. The drug is administered sublingually or orally at a dose of 0.25 mg/kg. The effect develops at the 6th minute, reaching its maximum at the 60–90th minute.

Verapamil helps reduce blood pressure by reducing peripheral vascular resistance, arteriolar dilatation, diuretic and natriuretic effects. Oral administration of the drug at a dose of 40 mg is possible; if ineffective, slow intravenous administration at a rate of 0.1–0.2 mg/kg.

How to recognize a hypertensive crisis

Knowing the signs of a hypertensive crisis, you can assess the changes occurring in the body and provide the victim with the necessary assistance in a timely manner.

Main symptoms:

- nausea;

- headache;

- blurred vision;

- chest pain;

- weakness.

The causes of hypertensive crisis are:

- severe injuries, burns, concussion;

- state of stress;

- disruption of the kidneys, heart, endocrine system;

- preeclampsia in pregnancy;

- taking drugs or alcohol;

- advanced hypertension or improper treatment of this disease.

It is important to monitor the dynamics of blood pressure levels in cases of traumatic brain injury, preeclampsia and eclampsia in pregnant women, as well as in a state of drug intoxication.