Stenosis is a term used to describe a narrowing of the lumen of any hollow organ or blood vessel. Often stenosis is also called a stricture, for example, urethral stricture is a narrowing of the urethra.

Narrowing of the lumen of an organ inevitably leads to disruption of its function. As a rule, stenosis increases over time and does not go away without treatment. It can act as a symptom or complication of many diseases.

What are the causes of stenosis?

There are many different causes of stenosis. The main ones:

- Congenital malformations (for example, congenital urethral valves, congenital intestinal obstruction due to intestinal underdevelopment).

- Proliferative inflammation of the organ wall is an inflammatory process in which tissue proliferation occurs.

- Scarring of the organ wall after damage, inflammation, or ulcers.

- Benign and malignant tumors.

- In vessels, the cause of stenosis is often blood clots and atherosclerotic plaques.

- Compression of a hollow organ from the outside, for example, by a tumor located in a neighboring organ.

- Hypertrophy of the organ wall - for example, this condition often causes narrowing of the pylorus of the stomach.

- Injuries and osteophytes (bone growths) can cause stenosis of bone canals, in particular the spinal canal.

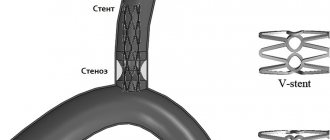

Stent restenosis is not a death sentence

In an era of rapid growth of minimally invasive operations on the vascular bed throughout the world, in particular in the Russian Federation, the issue of the risk of repeated interventions in the event of restenosis of previously implanted stents remains unresolved. The current state of technology makes it possible to create a new generation of stents with a partially biodegradable frame and reduce the risk of re-operations by an average of 10%. This means that only 10 patients out of 100 will return to hospital within a year after surgery and be offered treatment.

The causes of stent restenosis in patients are both mechanical damage (underexplosion of the stent, stent breakage, long stented section, the presence of calicinosis, incomplete coverage of the atherosclerotic plaque by the stent, weak radial rigidity of the metal stent frame, lack of drug coating on the stent) and clinical factors (presence of sugar diabetes and chronic kidney disease, resistance to the drug coating of the stent, allergic reactions to stent components).

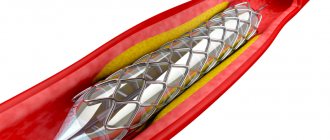

Today, stent overgrowth is not an incurable condition. Endovascular surgeons have modern diagnostic technologies at their disposal that allow them to identify the probable cause of restenosis and perform the necessary treatment. In particular, one of these diagnostic methods is optical coherence tomography (OCT). This method allows you to look inside the vessel, assess the condition of the vascular wall and stent frame, and also identify the mechanical causes of restenosis.

Possible treatment options for restenosis may be: implantation of a new stent with different frame characteristics and drug coating inside the “old” stent, inflation of the “old” stent with a drug-loaded balloon, and/or consideration of open surgery - coronary artery bypass grafting. There are no official recommendations regulating the number of implanted stents in the same location of the artery; however, in clinical practice, most often no more than 3 layers of stents are permissible.

We would like to present a clinical case of a 51-year-old patient who applied to the Federal State Budgetary Institution “National Medical Research Center for TPM” of the Ministry of Health of Russia 6 months after stenting of the coronary arteries with complaints of resumption of angina attacks. Coronary angiography revealed restenosis in a previously implanted stent in the anterior descending artery (Figure 1). Optical coherence tomography confirmed the phenomenon of a decrease in the diameter of the stent in the long-term follow-up period (“stent recoil”) due to its insufficient radial stiffness (Figure 2).

After inflation with high-strength balloons, a drug-coated balloon was applied. However, on control angiography, a pronounced contrast defect remained, caused by a torn area of excess restenotic tissue. Therefore, an additional second stent with a greater radial force and a more durable frame was implanted. On control angiography, a good result was achieved, the stent was completely expanded (Figure 3,4). The patient noted improvement in health, absence of angina attacks and was discharged from the hospital.

Figure 1. Section of the anterior descending artery (ADA) with restenosis

Figure 2. Section of the anterior descending artery (ADA) with restenosis according to OCT data (the white line marks the stent)

Figure 3. Result after LAD stenting

Figure 4. Result after LAD stenting according to OCT data (the white line marks the stent)

In which organs can stenosis occur?

Stenosis can occur in any organs that have a lumen, in the heart and in vessels of different diameters, in various anatomical canals. Symptoms of stenosis are very diverse - they depend on the affected organ and impaired functions.

Common types of stenoses:

- Stenoses of the digestive system organs: esophagus, stomach, intestines, bile ducts, pancreatic duct, papilla of Vater (the place where the bile duct and pancreatic duct enter the duodenum).

- Stenosis of the respiratory tract: larynx, trachea, bronchi.

- Stenoses of organs of the cardiovascular system: heart valves, aorta, arteries and veins of different diameters.

- Stenoses of the urinary system organs: ureters, urethra, bladder neck, renal arteries.

- Spinal stenosis. Frequent causes are previous spinal injuries, osteophytes, tumors, herniated intervertebral discs.

- Stenoses in the nervous system: the most striking example is non-communicating hydrocephalus; Among the causes may be tumor processes in the brain and spinal cord.

Book a consultation around the clock +7+7+78

Medical Internet conferences

Introduction. The muscular bridge (MM), partially blocking the lumen of the coronary artery, is a congenital anatomical variant and is more common in the LAD. MM causes the development of IHD through two independent mechanisms, depending on its anatomical features (extent, thickness, localization). One of the mechanisms is direct mechanical compression of the LAD at the time of systole, which helps to delay diastolic relaxation of the artery, reduces the blood flow reserve and the severity of perfusion. The second mechanism is an increase in the progression of coronary atherosclerosis, causing stenosis of the LAD proximal to the MM, due to endothelial damage against the background of abnormal hemodynamics (retrograde blood flow to the orifice of the LAD during systole). The anatomical features of MM are associated with the choice of tactics and outcome of intervention in patients with coronary artery disease. Thus, in cases of stenting for an atherosclerotic plaque located proximal to the MM, it is possible to position part of the stent in the area of the MM, which increases the frequency of long-term adverse outcomes, mainly due to disorders in the area of the stented area of the MM. Thus, the anatomical features of MM must be taken into account when diagnosing and choosing treatment tactics for coronary artery disease in patients with this anatomical feature.

Purpose of the study. To determine the effect of the degree of systolic compression of the LAD caused by MM on the incidence of cardiovascular events in the immediate and long-term period after stenting of an atherosclerotic lesion located proximal to the MM.

Material and methods. The prospective study included 17 patients with coronary artery disease who underwent LAD stenting between January 2012 and August 2013. Inclusion criteria were: the presence of a MM in the middle third of the LAD and stenosis located proximal to the MM. IVUS was used to position the stents to prevent unintentional stenting of a portion of the MM. The angiographic effectiveness of stenting was assessed immediately after the procedure, as well as after 6 months. The immediate results were taken into account: the development of myocardial infarction (MI) in the immediate period after stenting, as well as the presence and degree of residual stenosis. As long-term clinical outcomes, the degree of stent stenosis was assessed depending on the initial degree of systolic compression of the artery, as well as the presence of complications (myocardial infarction, the need for repeated revascularization in a given localization, deaths). The presence and degree of residual stenosis was determined by control angiography and IVUS immediately after stenting and 6 months later. In this study, only drug-eluting stents were used.

Statistical processing of the results was performed in the Statistica 7.0 application package; the data are presented in the form “Median (standard deviation)”. Differences in the frequencies of outcomes were determined using Fisher's and c2 tests; differences in unrelated groups by quantitative characteristics were assessed using the Mann-Whitney test.

Results. The average age of the patients included in the study was 56.6 (4.7) years, the number of men was 13. According to the results of coronary angiography (CAG), the myocardial bridge with a maximum degree of narrowing in systole of more than 50% was observed in 8 patients (group I, men - 6, women - 2), and less than 50% - in 9 patients (group II, men - 7, women - 2), the difference between the groups by gender and age was not clinically significant (p(c2) = 0.66, p(U)= 0.45, respectively). In all patients, after stent implantation, restoration of optimal antegrade blood flow was noted.

There were no adverse outcomes in the immediate period (acute coronary circulatory disorders, artery dissections, etc.) in both groups.

During the 6-month follow-up, there were no acute coronary events or the need for repeated myocardial revascularization in patients of both groups I and II.

In the long-term period, the frequency of stent restenosis did not differ in groups of patients with different degrees of systolic compression of the artery: thus, in group 1, restenosis occurred in 2 patients, and in group 2 – in 1 patient (p(c2) = 0.55).

Conclusions. A prerequisite for stenting the LAD with a distally located MM is the use of IVUS to control the positioning of the stent. There was no effect of the degree of systolic compression of the LAD (more or less than 50%) caused by the myocardial bridge on the incidence of adverse events after coronary stenting in the area of a proximal atherosclerotic plaque. Further study of the relationship between the anatomical parameters of the MM and the frequency of restenosis of stents implanted for proximal atherosclerotic lesions of the LAD is necessary.

Stenoses in oncology

Malignant tumors often block the lumen of hollow organs, disrupting their functions. In this case, the patient’s condition always worsens significantly, and the prognosis becomes more serious. If radical surgery for a malignant neoplasm is not possible, then the doctor performs palliative surgery to eliminate stenosis, restore organ function, and improve the patient’s condition.

The patient's condition improves when the tumor begins to disintegrate - it no longer blocks the lumen of the organ. The tumor disintegrates under the influence of chemotherapy, less often on its own. Substances that are released into the blood during massive decay of tumor cells poison the body and can lead to serious complications.

How is stenosis detected?

If stenosis is suspected, the doctor may order the following tests:

- X-ray and fluoroscopy (including contrast-enhanced).

- Angiography is radiography with the introduction of a radiopaque solution into the vessels.

- Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These studies can also be performed with contrast enhancement.

- Ultrasound examination (ultrasound). Dopplerography is also performed - studying blood flow in vessels using ultrasound.

- Endoscopic studies, for example, fibroesophagogastroduodenoscopy (FEGDS) to detect stenosis of the esophagus, stomach, duodenum.