Symptoms (signs)

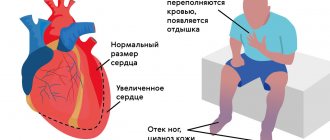

Clinical manifestations depend on the frequency of the escape rhythm; with a rare rhythm, a decrease in cardiac output and an increase in blood pressure due to an increase in peripheral vascular resistance are observed, which leads to pronounced disturbances in organ hemodynamics.

Classification: see Atrioventricular block.

Types • Proximal AV - third degree block (nodal, AV - type A block) - the conduction of impulses from the atria to the ventricles is completely interrupted at the level of the atrioventricular node •• The frequency of ventricular contractions is determined by the activity of the replacement pacemaker from the atrioventricular junction and is usually not exceeds 40–50 per minute •• Ventricular complexes are not widened, the duration of the QRS complex is £0.11 s •• Episodes of loss of consciousness are possible •• Complete AV blockades can be acute (transient) or chronic (permanent). Acute AV blockades of the third degree complicate the course of posteroinferior MIs 3–4 times more often than infarctions of anterior localization, last in most cases 2–3 days, rarely become permanent • Distal AV blockade III degree (trunk, AV blockade type B ) occurs if the conduction of impulses from the atria to the ventricles completely stops below the atrioventricular node (the level of the His bundle or the level of the His bundle branches) - the so-called three-fascicular block •• The replacement rhythm source is usually located in one of the branches of the His bundle •• The QRS complexes are widened and deformed, QRS ³0.12 s •• Heart rate 30–40 per minute or less •• Acute distal complete AV blocks complicating myocardial infarction of the anterior wall are prognostically unfavorable (mortality up to 80%), their occurrence is due to severe damage to the interventricular septum •• Chronic distal AV blockades of the third degree in half of the cases are caused by sclerotic and degenerative changes in the pathways ••• Idiopathic bilateral fibrosis of the pedicles - Lenegra's disease (idiopathic chronic heart block), which occurs mainly in young and middle age ••• Progressive sclerosis and calcification of the membranous part and the upper part of the muscular part of the interventricular septum - Lev's disease.

What are the dangers of heart blocks?

During blockades, bradycardia (slow pulse) develops, because not every impulse passes to the heart, the patient may feel interruptions in the functioning of the heart, weakness, etc. For more information about the symptoms of bradycardia, see “Bradycardia: Symptoms and Treatment.”

The most dangerous condition is when a complete block occurs, in which case the heart stops for a few seconds, this may be enough for the patient to lose consciousness. Usually, the heart “starts” on its own, but sometimes this may not happen. Imagine a light bulb with bad wiring and a rusty socket: You turn it on, and it begins to short out - it’s on, then it’s off, it blinks, then it blinks, i.e. works intermittently. Knock - it will light up, then go out again. But at one moment it can go out forever. It’s the same with the heart: the impulse sometimes passes, sometimes it doesn’t, sometimes the heart works normally, sometimes intermittently, sometimes weakness, sometimes fainting, but at one moment it may stop and not start.

You can always buy a new light bulb. Unfortunately, this does not work with the heart; its failure inevitably leads to the death of the patient.

Treatment

Treatment • Implantation of pacemaker is indicated (see Cardiac pacing), in case of MI - temporary endocardial pacemaker • Intensive therapy is necessary if bradycardia causes Morgagni-Adams-Stokes syndrome (or its equivalents - shock, pulmonary edema), arterial hypotension, anginal pain, progressive decrease Heart rate or increase in ectopic ventricular activity • Temporary endocardial or transthoracic external pacemaker • Drug therapy allows time to prepare for pacemaker: •• atropine 1 mg IV, repeat after 3-5 minutes until effect is achieved or total dose is 0.04 mg/kg •• if there is no effect - aminophylline IV slowly 240-480 mg •• if there is no effect - dopamine 100 mg or epinephrine 1 mg in 250 ml 5% glucose solution IV, gradually increasing the infusion rate to achieving a minimum sufficient heart rate.

Synonym. Third degree atrioventricular block.

ICD-10 • I44.2 Complete atrioventricular block

Note. Frederick's syndrome (Frederick's phenomenon) is a combination of complete AV block with atrial fibrillation or flutter. The ECG shows waves of flutter (FF) or fibrillation (ff) of the atria, there are no P waves, but the ventricular rhythm is correct - 30-50 per minute, QRS complexes can be widened and deformed. Frederick's syndrome is observed in 10–27% of cases of complete AV block.

Symptoms

AV block is most often accompanied by angina pectoris, severe heart failure and sudden changes in blood pressure. The first degree of the disease does not have pronounced symptoms. A distinctive feature is minor deviations in the electrocardiogram.

Most often, the patient experiences the following symptoms:

Author:

Kirill Savchenko

Didn't understand the article?

Ask in the comments right now and get an answer a little later.

auto RU

- Severe shortness of breath;

- Muscle weakness;

- Dizziness;

- General malaise;

- Weakness after physical activity;

- Increased irritability;

- Blue tint of the nail plate on the hands and feet;

- Numbness in the arms and legs. A similar phenomenon is most often observed in the early morning, when the body was in a period of prolonged calm;

- Distracted consciousness. The person does not concentrate on objects and assigned tasks;

- Pale skin. This sign indicates a circulatory disorder.

Cardiology.

The heart begins to beat “wrongly” - too slowly or too fast, or the beats follow one after another at different intervals, otherwise suddenly an extraordinary, “extra” contraction will appear, or, conversely, a pause, “loss”. In medicine, such conditions are called cardiac arrhythmias. They appear due to problems in the conduction system of the heart, which ensures regular and coordinated contractions of the heart muscle. Another group of diseases of this system is heart block. Many blockages exist unnoticed by the patient, but often indicate the presence of another heart disease. The most severe blockades are manifested by disturbances in the rhythm and contractility of the heart. Often these diseases lead to dysfunction of the heart or the development of serious complications in other organs. In turn, they themselves can be complications of other serious diseases. Heart disease and mortality statistics show that heart rhythm disorders as a cause of death account for about 10-15 percent of all heart diseases. Therefore, for the study, diagnosis and treatment of arrhythmias, there is a special branch of cardiology - arrhythmology.

HEART ARRHYTHMIAS Disturbances in the frequency, rhythm and sequence of contractions of the heart. Arrhythmias can occur due to structural changes in the conduction system due to heart disease and (or) under the influence of autonomic, endocrine, electrolyte and other metabolic disorders, during intoxication and certain medicinal effects. Often, even with pronounced structural changes in the myocardium, arrhythmia is caused partly or mainly by metabolic disorders. The factors listed above affect the basic functions (automaticity, conductivity) of the entire conduction system or its parts, causing electrical heterogeneity of the myocardium, which leads to arrhythmia. In some cases, arrhythmias are caused by individual congenital anomalies of the conduction system. The severity of the arrhythmic syndrome may not correspond to the severity of the underlying heart disease. Arrhythmias are diagnosed mainly by ECG. Most arrhythmias can be diagnosed and differentiated by clinical and electrocardiographic features. Occasionally, a special electrophysiological study (intracardiac or intraesophageal electrography with stimulation of parts of the conduction system) performed in specialized cardiological institutions is necessary. Treatment of arrhythmias always includes treatment of the underlying disease and antiarrhythmic measures themselves. Normal rhythm is ensured by the automatism of the sinus node and is called sinus. The resting sinus rate in most healthy adults is 60-75 beats/min. Sinus arrhythmia is a sinus rhythm in which the difference between the RR intervals on the ECG exceeds 0.1 s. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia is a physiological phenomenon; it is more noticeable (by pulse or ECG) in young people and with slow but deep breathing. Factors that increase sinus rhythm (physical and emotional stress, sympathomimetics) reduce or eliminate respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Sinus arrhythmia not related to breathing is rare. Sinus arrhythmia itself does not require treatment. Sinus tachycardia - sinus rhythm with a frequency of more than 90-100 per minute. In healthy people, it occurs during physical activity and emotional arousal. A pronounced tendency to sinus tachycardia is one of the manifestations of neurocirculatory dystonia; in this case, tachycardia noticeably decreases with breath holding. Temporary sinus tachycardia occurs under the influence of atropine, sympathomimetics, with a rapid decrease in blood pressure of any nature, after drinking alcohol. Sinus tachycardia is more persistent with fever, thyrotoxicosis, myocarditis, heart failure, anemia, and pulmonary embolism. Sinus tachycardia may be accompanied by a feeling of palpitations. Treatment should be aimed at the underlying disease. For tachycardia caused by thyrotoxicosis, the use of beta-blockers is of auxiliary importance. For sinus tachycardia associated with neurocirculatory dystonia, sedatives and beta-blockers (in small doses) may be useful; verapamil: for tachycardia caused by heart failure, cardiac glycosides are prescribed. Sinus bradycardia - sinus rhythm with a frequency of less than 55 per 1 min - is not uncommon in healthy, especially physically trained individuals at rest or during sleep. It is often combined with a noticeable respiratory arrhythmia, sometimes with extrasystole. Sinus bradycardia may be one of the manifestations of neurocirculatory dystonia. Sometimes it occurs with posterior phrenic myocardial infarction, with various pathological processes (ischemic, sclerotic, inflammatory, degenerative) in the area of the sinus node (sick sinus syndrome - see below), with increased intracranial pressure, decreased thyroid function, with some viral infections , under the influence of certain drugs (cardiac glycosides, beta-blockers, verapamil, sympatholytics, especially reserpine). Sometimes bradycardia manifests itself as an unpleasant sensation in the heart area. Treatment is aimed at the underlying disease. For severe sinus bradycardia caused by neurocirculatory dystonia and some other causes, belloid, alupent, aminophylline are sometimes effective, which can have a temporary symptomatic effect. In rare cases (with severe symptoms), temporary or permanent cardiac pacing is indicated. Ectopic rhythms. When the activity of the sinus node weakens or ceases, replacement ectopic rhythms may occur (from time to time or constantly), that is, heart contractions caused by the manifestation of automatism in other parts of the conduction system or myocardium. Their frequency is usually less than the frequency of sinus rhythm. As a rule, the more distal the source of the ectopic rhythm, the lower the frequency of its impulses. Ectopic rhythms can occur with inflammatory, ischemic, sclerotic changes in the area of the sinus node and in other parts of the conduction system; they can be one of the manifestations of sick sinus syndrome (see below). Supraventricular ectopic rhythm may be associated with autonomic dysfunction and overdose of cardiac glycosides. Occasionally, the ectopic rhythm is caused by an increase in the automaticity of the ectopic center; in this case, the heart rate is higher than with a replacement ectopic rhythm (accelerated ectopic rhythm). The presence of an ectopic rhythm and its source are determined only by ECG. The atrial rhythm is characterized by changes in the configuration of the P wave. Its diagnostic signs are unclear. Sometimes the shape of the P wave and the duration of P-Q changes from cycle to cycle, which is associated with migration of the pacemaker through the atria. Atrioventricular rhythm (rhythm from the atrioventricular junction) is characterized by inversion of the P wave, which can be recorded near the ventricular complex or superimposed on it. The frequency of the replacement atrioventricular rhythm is 40-50 per 1 min, for the accelerated rhythm it is 60-100 per 1 min. If the ectopic center is somewhat more active than the sinus node, and the reverse conduction of the impulse is blocked, then conditions arise for incomplete atrioventricular dissociation, while periods of sinus rhythm alternate with periods of replacement atrioventricular (rarely ventricular) rhythm, a feature of which is more a rare atrial rhythm (P) and an independent but more frequent ventricular rhythm (QRST). Ectopic ventricular rhythm (no regular P wave, ventricular complexes are deformed, frequency 20-50 per minute) usually indicates significant changes in the myocardium; at a very low frequency of ventricular contractions, it can contribute to the occurrence of ischemia of vital organs.

Treatment of arrhythmia and heart block For the above ectopic rhythms, the underlying disease should be treated. Atrioventricular rhythm and incomplete atrioventricular dissociation associated with autonomic dysfunction can be temporarily corrected with atropine or an atropine-like drug. If the ventricular rate is infrequent, temporary or permanent pacing may be necessary. Extrasystoles are premature contractions of the heart caused by the occurrence of an impulse outside the sinus node. Extrasystole can accompany any heart disease. In no less than half of the cases, extrasystole is not associated with heart disease, but is caused by vegetative and psycho-emotional disorders, drug treatment (especially cardiac glycosides), electrolyte imbalances of various nature, consumption of alcohol and stimulants, smoking, and reflex effects from internal organs. Occasionally, extrasystole is detected in apparently healthy individuals with high functional capabilities, for example, in athletes. Physical activity generally provokes extrasystole associated with heart disease and metabolic disorders, and suppresses extrasystole caused by autonomic dysregulation. Extrasystoles can occur in a row, two or more - paired and group extrasystoles. The rhythm in which each normal systole is followed by an extrasystole is called bigeminy. Especially unfavorable are hemodynamically ineffective early extrasystoles that occur simultaneously with the T wave of the previous cycle or no later than 0.05 s after its end. If ectopic impulses are formed in different foci or at different levels, then polytopic extrasystoles arise, which differ from each other in the shape of the extrasystolic complex on the ECG (within one lead) and in the size of the pre-extrasystolic interval. Such extrasystoles are often caused by significant changes in the myocardium. Sometimes long-term rhythmic functioning of the ectopic focus is possible along with the functioning of the sinus pacemaker - parasystole. Parasystolic impulses follow a regular (usually rarer) rhythm, independent of sinus rhythm, but some of them coincide with the refractory period of the surrounding tissue and are not realized. On the ECG, atrial extrasystoles are characterized by a change in the shape and direction of the P wave and a normal ventricular complex. The post-extrasystolic interval may not be increased. With early atrial extrasystoles, there is often a violation of atrioventricular and intraventricular conduction (usually in the form of right leg block) in the extrasystolic cycle. Atrioventricular (from the area of the atrioventricular junction) extrasystoles are characterized by the fact that the inverted P wave is located near the unchanged ventricular complex or superimposed on it. Possible disruption of intraventricular conduction in the extrasystolic cycle. The post-extrasystolic pause is usually increased. Ventricular extrasystoles are distinguished by a more or less pronounced deformation of the QRST complex, which is not preceded by a P wave (with the exception of very late ventricular extrasystoles, in which a normal P wave is recorded, but the P-Q interval is shortened). The sum of the pre- and post-extrasystolic intervals is equal to or slightly exceeds the duration of the two intervals between sinus contractions. With early extrasystoles against the background of bradycardia, there may be no post-extrasystolic pause (intercalated extrasystoles). For left ventricular extrasystoles in the QRS complex in lead V, the largest is the R wave, directed upward, while for the right ventricular, the S wave is directed downward.

Symptoms of arrhythmia and heart block

Patients either do not feel extrasystoles, or feel them as an increased push in the heart or cardiac arrest. When examining the pulse, extrasystole corresponds to a premature weakened pulse wave or loss of the next pulse wave, and during auscultation - premature heart sounds. The clinical significance of extrasystoles may vary. Rare extrasystoles in the absence of heart disease usually do not have significant clinical significance. An increase in extrasystoles sometimes indicates an exacerbation of an existing disease (coronary heart disease, myocarditis, etc.) or glycoside intoxication. Frequent atrial extrasystoles often foreshadow atrial fibrillation. Particularly unfavorable are frequent early, as well as polytopic and group ventricular extrasystoles, which in the acute period of myocardial infarction and during intoxication with cardiac glycosides can be a harbinger of ventricular fibrillation. Frequent extrasystoles (G or more in 1 minute) can themselves contribute to the worsening of coronary insufficiency. Treatment of arrhythmia and heart block The factors that led to extrasystole should be identified and, if possible, eliminated. If extrasystole is associated with a specific disease (myocarditis, thyrotoxicosis, alcoholism, etc.), then the treatment of this disease is of decisive importance for eliminating arrhythmia. If extrasystoles are combined with severe psycho-emotional disorders (regardless of the presence or absence of heart disease), sedative treatment is important. Extrasystoles due to sinus bradycardia, as a rule, do not require antiarrhythmic treatment; sometimes they can be eliminated with belloid (1 tablet 1-3 times a day). Rare extrasystoles in the absence of heart disease also usually do not require treatment. If treatment is considered indicated, then an antiarrhythmic drug is selected taking into account contraindications, starting with lower doses, keeping in mind that propranolol (10-40 mg 3-4 times a day), verapamil (40-80 mg 3-4 times a day) day), quinidine (200 mg 3-4 times a day) is more active with supraventricular extrasystoles; lidocaine (100 mg intravenously), novocainamide (250-500 mg orally 4-6 times a day), diphenin (100 mg 2-4 times a day), etmozin (100 mg 4-6 times a day ) - for ventricular extrasystoles, cordarone (200 mg 3 times a day for 2 weeks, then 100 mg 3 times a day) and disopyramide (200 mg 2-4 times a day) - for both. If extrasystoles occur or become more frequent during treatment with cardiac glycosides, they should be temporarily canceled and a potassium supplement prescribed. If early polytopic ventricular extrasystoles occur, the patient must be hospitalized; the best remedy (along with intensive treatment of the underlying disease) is intravenous administration of lidocaine. Paroxysmal tachycardia is attacks of ectopic tachycardia, characterized by a regular rhythm with a frequency of about 140-240 per minute with a sudden onset and sudden end. The etiology and pathogenesis of paroxysmal tachycardia are similar to those of extrasystole. According to the ECG, in most cases it is possible to distinguish supraventricular (atrial and atrioventricular) and ventricular tachycardias. Atrial paroxysmal tachycardia is characterized by strict rhythm, the presence on the ECG of unchanged ventricular complexes, in front of which a slightly deformed P wave may be noticeable. Atrial tachycardia is often accompanied by a violation of atrioventricular and (or) intraventricular conduction, most often along the right bundle branch. Atrioventricular tachycardia (from the area of the atrioventricular junction) is characterized by the presence of a negative P wave, which can be located near the QRST complex or more often superimposed on it. The rhythm is strictly regular. Intraventricular conduction disturbances are possible. It is not always possible to distinguish atrial and atrioventricular tachycardia from an ECG. Sometimes in such patients, outside of paroxysm, extrasystoles are recorded on the ECG, occurring at the same level. Ventricular tachycardia is characterized by significant deformation of the QRST complex. The atria can be excited independently of the ventricles in the correct rhythm, but the P wave is difficult to distinguish. The shape and amplitude of the ORS T complex and the contour of the isoelectric line vary slightly from cycle to cycle, and the rhythm is usually not strictly regular. These features distinguish ventricular tachycardia from supraventricular tachycardia with bundle branch block. Sometimes, within several days after a paroxysm of tachycardia, negative T waves are recorded on the ECG, less often - with a shift in the ST segment - changes designated as post-tachycardia syndrome. Such patients need observation and exclusion of small focal myocardial infarction.

Symptoms of arrhythmia and heart block

A paroxysm of tachycardia is usually felt as an attack of palpitations with a distinct beginning and end, lasting from a few seconds to several days. Supraventricular tachycardia is often accompanied by other manifestations of autonomic dysfunction - sweating, excessive urination at the end of the attack, increased intestinal motility, and a slight increase in body temperature. Prolonged attacks may be accompanied by weakness, fainting, discomfort in the heart area, and in the presence of heart disease - angina pectoris, the appearance or worsening of heart failure. What is common to different types of supraventricular tachycardia is the possibility of at least temporary normalization of the rhythm during massage of the carotid sinus area. Ventricular tachycardia is less common and is almost always associated with heart disease. It does not respond to massage of the carotid sinus and more often leads to impaired blood supply to organs and heart failure. Ventricular tachycardia, especially in the acute period of myocardial infarction, may be a harbinger of ventricular fibrillation.

Treatment of arrhythmia and heart block

During an attack, it is necessary to stop exertion, it is important to calm the patient, and use sedatives if necessary. It is always necessary to exclude relatively rare special situations when paroxysm of tachycardia is associated with intoxication with a cardiac glycoside or with weakness of the sinus node (see below); Such patients should be immediately hospitalized in the cardiology department. If these situations are excluded, then with supraventricular tachycardia in the first minutes of the attack, stimulation of the vagus nerve is necessary - vigorous massage of the carotid sinus area (contraindicated in old people) alternately on the right and left, inducing gagging, pressure on the abdominals or eyeballs. Sometimes the patient himself stops the attack by holding his breath, straining, turning his head and other techniques. If vagotropic maneuvers are ineffective, it is advisable to repeat them later, against the background of drug treatment. Taking 40-60 mg of propranolol at the beginning of an attack sometimes stops it after 15-20 minutes. IV administration of verapamil (2-4 ml of 0.25% solution) or propranolol (up to 5 ml of 0.1% solution), or procainamide (5-10 ml of 10% solution) works faster and more reliably. These drugs must be administered slowly, over several minutes, while constantly monitoring blood pressure. One patient should not be administered either verapamil or propranolol. In case of significant hypotension, mezaton is pre-administered subcutaneously or intramuscularly. In some patients, digoxin administered intravenously is effective (if the patient did not receive cardiac glycosides in the days before the attack). If the attack is not stopped, and the patient’s condition worsens (which is rare with supraventricular tachycardia), then the patient is sent to a cardiology hospital to stop the attack by frequent intra-atrial or transesophageal stimulation of the atria or using electrical pulse therapy. Treatment of ventricular tachycardia should, as a rule, be carried out in a hospital. The most effective is intravenous administration of lidocaine (for example, 75 mg intravenously, repeating 50 mg every 5-10 minutes, monitoring ECG and blood pressure, up to a total dose of 200-300 mg). If the patient's condition is serious, associated with tachycardia, electric pulse treatment cannot be postponed. For both supraventricular and ventricular tachycardia, taking 50-75 mg of etacizin (daily dose 75-250 mg) may be effective; for ventricular tachycardia, ethmozin is effective - 100-200 mg (daily dose 1400-1200 mg). After a paroxysm of tachycardia, it is recommended to take an antiarrhythmic drug in small doses to prevent relapse; it is better to use an oral drug that relieves the paroxysm. Atrial fibrillation and flutter (atrial fibrillation). Atrial fibrillation is a chaotic contraction of individual groups of atrial muscle fibers, while the atria as a whole do not contract, and due to the variability of atrioventricular conduction, the ventricles contract arrhythmically, usually with a frequency of about 100-150 per minute. Atrial flutter is a regular contraction of the atria with a frequency of about 250-300 per minute; the frequency of ventricular contractions is determined by atrioventricular conduction; the ventricular rhythm can be regular or irregular. Atrial fibrillation can be persistent or parocoysmal. Its paroxysms often precede the persistent form. Fluttering occurs 10-20 times less frequently than flickering, and usually in the form of paroxysms. Sometimes atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation alternate. Atrial fibrillation can be observed with mitral heart defects, coronary heart disease, thyrotoxicosis, and alcoholism. Transient atrial fibrillation is sometimes observed with myocardial infarction, intoxication with cardiac glycosides, and alcohol. On the ECG, during atrial fibrillation, there are no P waves; instead, random waves are recorded, which are better visible in lead V1; ventricular complexes follow an irregular rhythm. With a frequent ventricular rhythm, blockade of the bundle branch, usually the right one, may occur. If, along with atrial fibrillation, there are disturbances in atrioventricular conduction or under the influence of treatment, the ventricular rate may be lower (less than 60 per minute - bradysystolic atrial fibrillation). Occasionally, atrial fibrillation is combined with complete atrioventricular block. With atrial flutter, instead of P waves, regular atrial waves are recorded, without pauses, having a characteristic sawtooth appearance; ventricular complexes follow rhythmically after every 2nd, 3rd, etc. atrial wave or arrhythmically if conduction often changes.

Symptoms of atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation may not be felt by the patient or may feel like a palpitation. With atrial fibrillation and flutter with an irregular ventricular rhythm, the pulse is arrhythmic, the sonority of heart sounds is variable. The filling of the pulse is also variable and some heart contractions do not produce a pulse wave at all (pulse deficiency). Atrial flutter with a regular ventricular rhythm can only be diagnosed by ECG. Atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular rhythm contributes to the appearance or worsening of heart failure. Both persistent and especially paroxysmal atrial fibrillation cause a tendency to thromboembolic complications.

Treatment of atrial fibrillation

In most cases, if atrial fibrillation is associated with an irreparable heart disease, the goal of treatment is a rational decrease in the ventricular rate (up to 70-80 per 1 min), for which systematic use of digoxin is used, with the addition, if necessary, of small doses of propranolol and potassium preparations. In some cases, cure of the underlying disease or its exacerbation (surgical elimination of the defect, compensation of thyrotoxicosis, successful treatment of myocarditis, cessation of alcohol intake) can lead to the restoration of sinus rhythm. In some patients with persistent atrial fibrillation lasting up to 2 years, the arrhythmia can be eliminated in the hospital with drug or electrical pulse treatment. The shorter the duration of the arrhythmia, the smaller the size of the atria and the severity of heart failure, the better the results of treatment. Defibrillation is contraindicated in cases of significant enlargement of the atria, a history of thromboembolic complications, myocarditis, rare ventricular rhythm (not related to treatment), severe conduction disturbances, intoxication with cardiac glycosides, and various conditions that prevent treatment with anticoagulants. Frequent paroxysms of atrial fibrillation in the past also indicate little prospect of restoring sinus rhythm. When treating persistent atrial fibrillation, anticoagulants are usually prescribed 2-3 weeks before defibrillation and for the same time after it. In most cases, treatment with quinidine is effective. If the test dose (0.2 g) is well tolerated, the drug is prescribed in increasing daily doses, for example: 0.6-0.8-1.0-1.2-1.4 g. The daily dose is given in fractions of 0.2 g per day. at intervals of 2-2.5 hours under ECG control. Electropulse therapy can also be used for defibrillation, especially if the patient’s condition is severe due to arrhythmia. The immediate effect of electrical pulse therapy is slightly higher for flutter than for atrial fibrillation. After restoration of sinus rhythm, long-term and persistent maintenance antiarrhythmic treatment is necessary, usually with quinidine at a dose of 0.2 g every 8 hours, or another antiarrhythmic drug. Paroxysms of atrial fibrillation often stop spontaneously. They can be eliminated by intravenous administration of verapamil, procainamide or digoxin. To relieve paroxysm of atrial flutter, frequent intra-atrial or transesophageal electrical stimulation of the atria can be used. With frequent paroxysms, systematic administration of an antiarrhythmic drug is necessary for prophylactic purposes. Systematic administration of digoxin sometimes helps to transform paroxysmal atrial fibrillation into a permanent form, which, after achieving a rational ventricular rate, is usually better tolerated by patients than frequent paroxysms. For frequent, poorly tolerated paroxysms that are not prevented by drug treatment, partial or complete dissection of the His bundle (usually with cardiac catheterization and the use of electrocoagulation or laser coagulation) may be effective, followed by permanent pacing if necessary. This intervention is performed in specialized institutions. Ventricular fibrillation and flutter, ventricular asystole can occur with any severe heart disease (usually in the acute phase of myocardial infarction), with pulmonary embolism, with an overdose of cardiac glycosides, antiarrhythmic drugs, with electrical trauma, anesthesia, with intracardiac manipulation, with severe general metabolic disorders . Symptoms are a sudden cessation of blood circulation, a picture of clinical death: absence of pulse, heart sounds, consciousness, hoarse agonal breathing, sometimes convulsions, dilated pupils (starts 45 s after the cessation of blood circulation). It is possible to differentiate between ventricular fibrillation and flutter and asystole using an ECG (in practice, with electrocardioscopy). When ventricular fibrillation occurs, the ECG appears as random waves of various shapes and sizes. Large-wave flicker (2-3 mV) is somewhat more easily reversible with adequate treatment, small-wave flicker indicates deep myocardial hypoxia. With ventricular flutter, the ECG is similar to the ECG with ventricular tachycardia, but the rhythm is faster. Ventricular flutter is hemodynamically ineffective. Asystole (i.e., the absence of electrical activity of the heart) corresponds to a straight line on the ECG. Previous arrhythmia has some auxiliary diagnostic value: early polytopic ventricular extrasystoles and ventricular tachycardia often precede ventricular fibrillation and flutter, increasing blockade - asystole. Treatment comes down to immediate external cardiac massage and artificial respiration, which should be continued until the effect is achieved (spontaneous heart sounds and pulse) or for the time necessary to prepare for electrical pulse therapy (for ventricular fibrillation and flutter) or temporary cardiac pacing (for asystole). Intracardiac administration of drugs (potassium chloride for atrial fibrillation, adrenaline for asystole) can be effective in some patients if the nature of the arrhythmia is established. During resuscitation, excess oxygenation and administration of sodium bicarbonate are important. To prevent relapses of life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias, it is necessary to administer intravenous lidocaine and potassium chloride for several days, and intensively treat the underlying disease. Heart blocks are cardiac dysfunctions associated with slowing or stopping the conduction of impulses through the conduction system. Based on localization, blockades are distinguished between sinoatrial (at the level of the atrial myocardium), atrioventricular (at the level of the atrioventricular node) and intraventricular (at the level of the His bundle and its branches). Based on severity, conduction slowdown is distinguished (each impulse is slowly conducted into the underlying parts of the conduction system, 1st degree blockade), incomplete blockades (only part of the impulses are carried out, 2nd degree blockade) and complete blockades (impulses are not conducted, cardiac activity is supported by the ectopic center of rhythm control, blockade III degree) Treatment of heart diseases by a cardiologist.

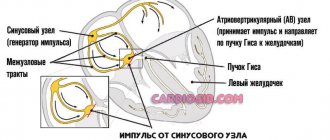

Conduction system of the heart

In general terms, the conduction system of the heart (the system responsible for conducting electrical impulses in the heart) is arranged as follows. The impulses are generated by the sinus node located in the right atrium. Along the intraatrial pathways, these impulses reach the atrioventricular (AV) node, where some delay of the impulses occurs: the atria and ventricles must contract at the same time. The impulse then travels along the bundle branches to the cells (cardiomyocytes) of the ventricles. The bundle of His consists of two legs - right and left. The left bundle branch consists of two branches - anterior and posterior.