Causes of heart murmurs, treatment

A heart murmur is a clinical manifestation of a nonspecific nature, which is not always a symptom of pathology.

For example, quite often a heart murmur in a newborn baby is a manifestation of the baby’s “transitional” state from intrauterine life to independent existence. However, this may also be a manifestation of pathology. Therefore, in addition to examination by a cardiologist, it is necessary to conduct a number of instrumental studies that will help make the correct diagnosis. Under no circumstances should the symptom be ignored. Possible causes of heart murmurs:

- congenital or acquired heart disease;

- VSD, endocarditis;

- infection of the heart muscle;

- damage to the aortic valve;

- anatomical abnormalities;

- mitral stenosis;

- hypertension;

- acute form of pericarditis.

Causes of heart murmurs in adults that are not related to cardiac pathology include age-related changes, chronic stress and psycho-emotional stress, and excessive physical activity.

Congenital heart defects

Classification. Several classifications of congenital heart defects have been proposed, common to them is the principle of subdividing defects according to their effect on hemodynamics. The most general systematization of defects is characterized by combining them, mainly according to their effect on pulmonary blood flow, into the following 4 groups.

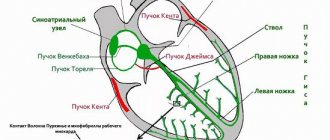

I. Defects with unchanged (or slightly changed) pulmonary blood flow: anomalies of the location of the heart, anomalies of the aortic arch, its coarctation of the adult type, aortic stenosis, atresia of the aortic valve; pulmonary valve insufficiency; mitral stenosis, atresia and valve insufficiency; triatrial heart, defects of the coronary arteries and conduction system of the heart.

II. Defects with hypervolemia of the pulmonary circulation:

III. Defects with hypovolemia of the pulmonary circulation:

Clinical manifestations and course are determined by the type of defect, the nature of hemodynamic disturbances and the timing of the onset of circulatory decompensation. Defects accompanied by early cyanosis (so-called “blue” defects) appear immediately or shortly after the birth of the child. Many defects, especially groups 1 and 2, have an asymptomatic course for many years and are detected by chance during a preventive medical examination of a child or when the first clinical signs of hemodynamic disorders appear in the patient’s adulthood. Defects of groups III and IV can be complicated relatively early by heart failure, leading to death.

Why does a heart murmur occur?

Heart murmurs are systolic, diastolic and systolic-diastolic.

Systolic murmurs are heard at the apex of the heart and can be caused by cardiac pathology or be a symptom of a disease not related to the heart. Doctors most often associate systolic murmur at the apex of the heart in a child with adaptation to the environment.

Diastolic is always associated with heart pathology. The main causes are stenosis of the atrioventricular orifices, insufficiency of the aortic valve or pulmonary trunk.

Why does a heart murmur occur?

- blood regurgitation;

- high blood flow speed;

- the passage of blood into the dilated chamber of the heart through a deformed hole.

Coronary heart disease and anemia

Most often, this is an increase in LV work (tachycardia, increased systolic blood pressure) or insufficiency of coronary blood flow (thrombosis in the coronary arteries, spasm). Less commonly, a decrease in perfusion pressure (DBP) or a violation of the oxygen transport function of the blood, etc. are considered as factors contributing to the development or progression of IHD.

For clarity, we present extracts from the medical histories of patients in whom these factors played the role of a “triggering mechanism.” The opinion that only men can wear pants, and women should be sophisticated and elegant, preferring skirts and dresses, is absolutely not relevant at the present time.

Clinical case 1

Patient Sh., 84 years old, was hospitalized in May 2013 with complaints of pressing pain in the chest with little physical activity and at rest.

For more than 30 years, high blood pressure numbers (up to 200/120 mm Hg) and type 2 diabetes mellitus have been recorded.

4 months ago suffered an acute myocardial infarction without a Q wave of the lateral wall of the left ventricle. During coronary angiography: the anterior interventricular branch (LAD) of the left coronary artery (LCA) is stenotic in the proximal third by 50%, in the distal third there are successive stenoses of 30–50%; the circumflex artery (CA) is stenotic in the middle third by 70%, the right coronary artery (RCA) is suboccluded in the anterior third, occluded in the middle third, the distal part is poorly contrasted by inter- and intraarterial anastomoses. Stenting of the middle third of the OA was performed. RCA recanalization failed.

Attention was drawn to the presence of mild hypochromic anemia (hemoglobin -106 g/l). The examination did not reveal a possible source of bleeding. He was discharged in satisfactory condition with a recommendation to take acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel, glucose-lowering therapy, and iron supplements.

At home, I took the recommended medications irregularly and did not visit a doctor.

About 2 months ago noted increasing weakness. Rare attacks of chest pain began to bother me. On the ECG dated May 10, 2013: against the background of sinus rhythm with a heart rate of 75 beats/min, there was pronounced depression of the ST segment in leads V2-6 (Fig. 1). He refused the proposed hospitalization.

Last 2 weeks attacks of chest pain of a pressing nature became more frequent, they began to occur with minimal physical activity and at rest, sublingual administration of nitroglycerin had a short-term effect, and a feeling of lack of air appeared. He went to the clinic, from where he was taken to the Central Clinical Hospital with a diagnosis of coronary artery disease, progressive angina.

Upon admission: the skin is pale. There is no swelling. BH - 18 in 1 min. Breathing is hard. Pulse - 72, blood pressure - 140/70 mm Hg. Art. on both hands. Systolic murmur at Botkin's point and at the apex, extending to the left axillary region.

ECG on admission (Fig. 2): sinus rhythm with heart rate 59 beats/min, slowing of atrioventricular conduction (PQ - 0.24 s). Slowing of conduction through the left atrium and ventricle. Left ventricular hypertrophy. Impaired repolarization in V2-5.

EchoCG: LV myocardial hypertrophy (LVMM - 240 g). Thickening of the interventricular septum (IVS), more pronounced in the basal part (1.6–1.8 cm), without signs of LV outflow tract obstruction. The thickness of the LVSD is 1.5 cm. The contractility of the LV myocardium is satisfactory (EF according to Teicholz - 63%), ESR - 3.6 cm, ESD - 5.5 cm, LA - 5.1 cm. No areas of impaired kinetics were identified. Changes in LV diastolic function according to the first type.

Coronary angiography (CAG) was performed urgently (Fig. 3): the left artery trunk was unchanged. The LAD is stenotic at the border of the anterior and middle thirds by 50%, and throughout the distal third there are successive stenoses of 30–60%. 1DV - anatomically small, stenotic at the mouth by 80%, occluded in the middle third, the distal part is poorly contrasted along the interarterial collaterals. The VTC is stenotic at the mouth up to 50%. The OB is anatomically large, passable along its entire length, previously implanted stents are without stenotic changes. The RCA is suboccluded in the anterior third, occluded in the middle third, the distal part is poorly contrasted by inter- and intraarterial anastomoses. Balanced type of coronary blood supply.

Considering the lack of dynamics of coronary artery stenosis compared to the coronary angiography of January 2013, percutaneous coronary intervention was not performed.

In the blood test: hemoglobin - 61 g/l, erythrocytes - 2.30 × 10 * 12, CP - 0.8, hematocrit - 18.5, leukocytes - 7.7 × 10 * 9.

Cardiac-specific enzymes (CPK MB, troponin T) were within the reference values.

In urine analysis: specific gravity - 1020, protein - 0.15, leukocytes - 0-5 in the field of view, erythrocytes - 100-150 in the field of view.

Additional targeted questioning revealed that over the past 4 months. There were repeated episodes of dark red urine, sometimes lasting for several days (gross hematuria?).

No convincing evidence of acute focal myocardial damage was obtained at the time of hospitalization. Considering the presence of severe anemia, a transfusion of washed erythrocytes was performed (1150 ml over 2 days) with a positive effect: the hemoglobin level increased to 100 g/l, the number of erythrocytes - to 3.59 × 10 * 12, hematocrit - to 29.4.

An ECG 1 day after the last blood transfusion shows normalization of the final part of the ventricular complexes in the chest leads (in V4 there is a weakly negative T wave).

The patient’s well-being improved significantly: over the next 3 days, when the motor mode was expanded to the level of physical activity corresponding to functional class 3, chest pain did not occur, the severity of shortness of breath decreased significantly, the volume of exercise was limited mainly by muscle fatigue. Episodes of gross hematuria did not recur. In satisfactory condition, the patient was transferred for further examination to the urology department.

Clinical case 2

Patient K., 50 years old, was hospitalized in the hospital in December 2014 with a clinical picture of progression of angina pectoris, shortness of breath that occurs with minimal physical activity, at rest, with an increase in general weakness over the last month.

History: hypertension with maximum known blood pressure values of 200/100 mmHg. Art. more than 15 years old; regularly takes antihypertensive drugs, but blood pressure control is irregular. In 2002, he suffered an AMI, and in the same year he underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) of the main area, RCA, and OA. In 2009, a clinical picture of progressive angina pectoris developed, and therefore stenting of a shunt to the left artery was performed. In May 2014, repeated AMI of the posterior wall of the left ventricle was performed; systemic thrombolysis, percutaneous coronary intervention with recanalization and stenting of CABG to the OA were performed. After discharge and before actual hospitalization, the patient’s condition was stable.

Concomitant diseases: type 2 diabetes mellitus, urolithiasis, chronic hemorrhoids, mild iron deficiency anemia has been registered since 2009 (I did not take iron supplements).

Upon admission: the skin is pale and dry. RR - 18 beats/min. Breathing is harsh, with a small amount of wheezing when exhaling. Heart sounds are muffled. Heart rate -76 beats/min. Blood pressure - 150/90 mm Hg. Art. on both hands.

An ECG was recorded against the background of a painful attack (Fig. 4): sinus rhythm, heart rate - 88 beats/min, ST segment shift upward from the baseline in leads III, aVF, V1. In leads I and aVL, the ST segment is shifted downward from the isoline. Q wave lasting 0.04 s in leads II, III, aVF.

EchoCG: LV myocardial hypertrophy (LVMM - 213 g, IVS - 1.5 cm, LVSD - 1.2 cm). Dilatation of the left atrium (5.3×6.1 cm). Violation of the diastolic function of the left ventricle of the first type. Hypokinesis of the diaphragmatic, posterobasal and posterolateral segments. EF - 54% according to Teicholz.

In the general blood test: hemoglobin - 70 g/l, erythrocytes - 4.29 × 10 * 12, hematocrit -23.5, CP - 0.48, hypochromia, anisocytosis, poikilocytosis (ovalocytes, target-shaped erythrocytes), leukocytes - 5, 9×10*9. Serum iron - 1.9.

Cardiac-specific enzymes (CPK MB, troponin T) were within the reference values.

Thus, no convincing data indicating acute focal myocardial damage was obtained at the time of hospitalization. It was suggested that the cause of angina progression was severe iron deficiency anemia, most likely posthemorrhagic. A transfusion of 630 ml of red blood cell suspension was performed during the first day, and parenteral administration of iron supplements was started.

Transfusion therapy was tolerated well. Anginal pain did not recur. On the ECG recorded after blood transfusion (Fig. 5): heart rate - 62 beats/min. The ST segment returned to baseline.

In the blood test after 1 day: the hemoglobin level increased to 105 g/l, the number of erythrocytes - to 5.71 × 10 * 12, hematocrit - 38.3, CP - 0.55, hypochromia, anisocytosis persisted. Leukocytes - 8x10*9.

The patient was in the ICU for 3 days; no antianginal therapy was required, since the angina attacks did not recur.

A search was carried out for a possible source of blood loss and an oncological search: a colonoscopy revealed stage 3 chronic combined hemorrhoids. No other pathology that could explain the presence of anemia was found.

A gradual expansion of the motor regime was carried out. Physical activity corresponding to level 3 of the functional class does not cause angina attacks and ECG signs of myocardial ischemia.

After 12 days, the patient was discharged in stable condition for further treatment on an outpatient basis. The surgeon recommended routine disarterization of hemorrhoids under ultrasound guidance.

Clinical case 3

Patient Z., 82 years old, was hospitalized in the hospital with complaints of discomfort behind the sternum, lack of air, occurring without a clear connection with physical activity, lasting up to 4–5 minutes; the day before there was a prolonged attack lasting more than 1 hour, severe weakness, sweating. The real deterioration of the condition has been noted over the last 3 days against the background of emerging hypotension.

Within 2 weeks. Before hospitalization, he took non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (ketorolac) for dorsalgia. 4 days ago I noticed the appearance of frequent, dark-colored, loose stools, and unusually low blood pressure—80/40 mm Hg. Art.

In 1995, he suffered an AMI of the LV inferior wall. In the same year, mammary coronary bypass surgery was performed in the left leg, CABG of the OA and RCA. In 2003 - linear aortofemoral bypass with a synthetic prosthesis on the left. The early postoperative period was complicated by the development of repeated AMI of the LV inferior wall.

Since 2009 - paroxysms of atrial fibrillation.

He constantly takes bisoprolol - 2.5 mg/day, perindopril - 5 mg/day, atorvastatin - 20 mg/day, warfarin - 5 mg/day. INR monitoring has not been carried out for more than a year.

Upon admission: the skin and visible mucous membranes are pale. The number of breaths is 20 per 1 minute. Breathing is weakened and harsh. Heart sounds are dull and rhythmic. Heart rate - 76 beats/min. Blood pressure - 110/70 mm Hg. Art.

Laboratory data: hemoglobin - 91 g/l, erythrocytes - 3.93 × 10 * 12, hematocrit - 33.0, CP - 0.84, leukocytes - 10.2–10.6 × 10 * 9, platelets - 223 × 10*9, anisocytosis, anisochromia.

Cardiac-specific enzymes: CPK - 268 on admission, after 10 hours - 319, CPK MB - 30 on admission, after 10 hours - 42, troponin T on admission - 177, after 10 hours - 538.

Serum iron - 13 µmol, iron transport proteins are within normal limits. Coagulogram: APTT - no coagulation, INR - no coagulation, fibrinogen - 3.3 g/l, D-dimer - 1147.

ECG (Fig. 6) upon admission: sinus rhythm, stage I AV block, cicatricial changes in the lower wall of the LV, ST segment displacement in leads II, III and avF, high R in V1-2. ECG archive not provided.

EchoCG: sclerosis and calcification of the aortic walls, rings and valves. LVMM - 204 g, IVS thickness - 1.0 cm, LVSD - 1.0 cm. Dilatation of the left parts of the heart (LA - 4.5x5.5 cm, left ventricle: ESV - 92, EDV - 171). Relative insufficiency of MV II degree. Hypokinesis of the middle posterior and posterolateral segments of the LV. Decreased global contractility of the LV myocardium (EF according to Teicholz - 47%). Type 1 left ventricular diastolic dysfunction.

Taking into account complaints, anamnesis, laboratory and instrumental data, the patient was diagnosed with repeated AMI of diaphragmatic and posterobasal localization.

Gastrointestinal bleeding could not be ruled out while taking NSAIDs and an oral anticoagulant, and therefore an urgent endoscopy was performed: endoscopic signs of chronic esophagitis, ulcer of the lower third of the esophagus Forrest II C. Acute gastric ulcer Forrest II B (without signs of ongoing bleeding). Forrest IB pyloric ulcer (with signs of ongoing bleeding). After endoscopic injection hemostasis, the bleeding stopped.

The cause of AMI was probably hypotension and anemia secondary to gastrointestinal bleeding. Conservative hemostatic and antiulcer therapy was started. It was decided to refrain from performing coronary angiography with possible percutaneous coronary intervention until the condition stabilizes.

During treatment, blood pressure levels stabilized at 120/85 mm Hg. Art., the hemoglobin level increased to 110 g/l, the number of erythrocytes increased to 5.71 × 10 * 12, hematocrit - 38.3, CP - 0.55, leukocytes - 8 × 10 * 9, hypochromia, anisocytosis persisted.

The level of CK activity decreased to 113 units, CPK MV - to 12.7, troponin T - to 225.

Endoscopy after 2 days: ulcer of the lower third of the esophagus Forrest III, acute gastric ulcer Forrest III, pyloric ulcer Forrest II C (no signs of bleeding, appearance of fibrin in the bottom area).

On the 3rd day of hospital stay, short-term attacks of compressive pain in the chest resumed (2 attacks: while eating and when trying to sit up in bed).

According to emergency indications, coronary angiography was performed (Fig. 7): the left coronary artery trunk is stenotic throughout the anterior and middle third up to 70%, suboccluded in the distal third with a transition to the orifices of the AV and LAD; The LAD is suboccluded at the mouth, stenotic in the anterior third by 80%, occluded in the middle third, the distal part is contrasted by a functioning mammary-coronary bypass. The OB is suboccluded at the mouth, stenotic in the anterior third by 80%; The RCA is suboccluded along the anterior and middle thirds, occluded at the border of the middle and distal thirds, the distal part is contrasted by interarterial anastomoses.

Right type of coronary blood supply.

The mammary coronary bypass from the right mammary artery in the distal third of the LAD is passable. Shunts to the OA and RCA are not visualized.

An attempt to recanalize stenotic arteries was unsuccessful due to severe calcification.

Over the next 24 hours, the condition showed negative dynamics: in the form of an increase in short-term attacks of angina pectoris, accompanied by pronounced ECG signs of myocardial ischemia (Fig. 8). There was a decrease in hemoglobin from 110 to 87 g/l, hematocrit - to 26.0.

Cardiac-specific enzymes are within normal limits. EchoCG: the size of the left chambers of the heart is the same, no new areas of disturbance of left ventricular wall movements were identified.

Gastroscopy: active bleeding from an acute defect in the mucous membrane of the cardioesophageal junction (Forrest I). Endoscopic bleeding control.

After transfusion of 600 ml of erythrocyte suspension, the condition showed positive dynamics: anginal pain and ECG signs of myocardial ischemia do not recur (Fig. 9), restoration of the level of hemoglobin (110 g/l), erythrocytes (3.85 × 10 * 12), hematocrit - 33.7.

At the control endoscopy after 10 days, there was a positive trend - a decrease in the size of ulcerative defects without signs of bleeding.

During therapy with proton pump inhibitors, β-blockers, clopidogrel 75 mg/day, red blood counts are stable, the motor mode is expanded and the level of load corresponds to FC 3.

XMECG: sinus rhythm, heart rate (over the course of the day/day/night): 78/77/78 beats/min, maximum heart rate—99 beats/min, minimum—64 beats/min. ST segment depression appears when heart rate increases above 90 beats/min.

The above cases demonstrate the possibility of coronary insufficiency manifesting against the background of a decrease in the oxygen transport capacity of the blood in both patients with severe and moderate coronary lesions. Elimination of anemia in all three cases contributed to an increase in coronary reserve and stabilization of the condition.

Why does a child's heart make noise?

There are many reasons, the most common:

- Abnormal state of venous return of the lungs - the pulmonary veins either do not communicate with the atrium on the right, or can fuse with the veins of the systemic circle.

- Pathology of the interventricular septum can develop independently or be combined with other cardiac pathologies.

- Coarctation of the aorta is a complex disease that requires consultation with a doctor: only a specialist can answer what a heart murmur at 2-3 years old means.

- Atrial septal disorder is a congenital heart defect characterized by a hole between the right and left atrium.

Heart murmur in an adult: symptoms

If we are talking about murmurs not related to cardiac pathology, then they can be combined with the following symptoms:

- fatigue, pale skin, weakness are inherent in anemia;

- weight loss, irritability, hand tremors are characteristic of thyroid diseases;

- mood swings, headache, dizziness, tachycardia indicate the presence of vegetative-vascular dystonia;

- swelling of the legs, shortness of breath, rapid heartbeat appear in late pregnancy.

Clinical manifestations of murmurs associated with cardiac pathology:

- rapid heartbeat, unstable blood pressure;

- dyspnea;

- increased sweating during sleep;

- “cold” hands and feet;

- swelling of the limbs;

- chest pain.

On our website you can make an appointment with a pediatric cardiologist and learn about the consequences of a heart murmur per month in a child. If necessary, the center can undergo a full range of examinations.

Symptoms

In addition to noises on auscultation, the patient may have other symptoms during history taking and examination:

- heart rhythm disturbances;

- poor tolerance to physical activity;

- cyanosis of lips, acrocyanosis ;

- swelling;

- fainting , dizziness ;

- cough;

- swelling of the neck veins;

- hepatomegaly - an increase in the size of the liver;

- increased sweating ;

- instability of blood pressure ;

- severe shortness of breath;

- asthenic physique;

- chest pain;

- in childhood - retardation in mental and physical development.

The symptom complex and severity of clinical manifestations depend on the underlying disease and the presence of complications:

- hereditary connective tissue dysplasia is characterized by joint hypermobility, increased skin extensibility, asthenic physique, myopia;

- Marfan syndrome is characterized by disproportionately long fingers and limbs, high stature, hypotonia of skeletal muscles, and the presence of signs of heart failure.

Depending on the existing pathology, the localization of noise changes. In case of aortic pathology, the murmur is recorded on the right in the second intercostal space, in case of disturbances in the functioning of the mitral valve, the murmur is heard at the apex of the heart, in case of dysfunction of the tricuspid valve, the murmur is recorded above the xiphoid process.

Treatment and prevention

Therapy directly depends on the cause. For murmurs not associated with cardiac pathology, the main emphasis is on treating the underlying disease. In case of endocrine disorders, therapy and adjustment will be carried out by an endocrinologist. If anemia causes noise, the help of a therapist is necessary. Treatment of murmurs associated with cardiac abnormalities is the responsibility of a cardiologist. In this case, both conservative therapy and surgical intervention may be required.

The main prevention will be a healthy lifestyle, including a balanced diet, feasible physical exercise, 8 hours of sleep, preventive intake of vitamins in the spring and autumn, and giving up bad habits.

If you have any questions or need advice from a specialist, please use the registration form on the website. Our specialist will help you understand the problem and tell you what functional heart murmurs are. Registration is available 24 hours a day.

Related services: Cardiac Check-up Diagnosis of heart rhythm disorders by ECG monitoring

Tests and diagnostics

The diagnosis is established based on the collection of complaints, examination, assessment of the medical history, auscultatory data, and the results of an additional examination. Patients are given:

- EchoCG;

- ECG;

- EchoCG with Doppler;

- fluorography;

- Holter ECG monitoring;

- cardiac probing;

- R-graphy of the chest organs;

- functional stress tests;

- CBC, biochemical blood test.

After careful listening and analysis of noise, further examination tactics are determined. Diagnosis is carried out by a cardiologist; if necessary, other specialists may be involved.