Causes of subarachnoid hemorrhage

In most cases, this condition is caused by non-traumatic factors:

- aneurysm rupture;

- rupture of a vessel in the brain against the background of arterial hypertension, atherosclerosis and other vascular diseases.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage in the brain can also be caused by traumatic factors:

- traumatic brain injury;

- brain contusion;

- fracture of the skull bones.

Main services of Dr. Zavalishin’s clinic:

- consultation with a neurosurgeon

- treatment of spinal hernia

- brain surgery

- spine surgery

Classification

In accordance with the etiofactor, subarachnoid hemorrhage is classified into post-traumatic and spontaneous. Traumatologists are often faced with the first option, and specialists in the field of neurology with the second. Depending on the area of hemorrhage, isolated and combined SAH are distinguished. The latter, in turn, is divided into subarachnoid-ventricular, subarachnoid-parenchymatous and subarachnoid-parenchymatous-ventricular.

In world medicine, the Fisher classification is widely used, based on the prevalence of SAH according to the results of CT scans of the brain. In accordance with it, they distinguish:

- class 1 - no blood

- class 2 - SAC less than 1 mm thick without clots

- class 3 - SAC more than 1 mm thick or with clots

- class 4 - predominantly parenchymal or ventricular hemorrhage.

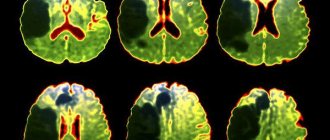

CT scan of the brain. Blood in the subarachnoid cerebrospinal fluid spaces on the right. (photo by V.N. Vishnyakov)

Clinical picture of subarachnoid hemorrhage

This condition develops rapidly against the background of a person’s normal well-being and manifests itself:

- sharp acute headache, worsening with the slightest physical activity;

- nausea, vomiting;

- convulsions;

- psycho-emotional disorders (fear, agitation, drowsiness);

- increased body temperature (up to febrile and subfebrile levels);

- disorders of consciousness (from stupor to fainting, coma);

- symptoms of damage to the oculomotor nerve (gaze paresis, drooping eyelid), hemorrhage in the eyeball.

In half of the cases, this condition leads to death. The main complications and consequences of subarachnoid hemorrhage:

- spasm of cerebral vessels caused by ischemia;

- recurrence of an aneurysm episode (may occur early or several weeks after the first episode);

- hydrocephalus (in the initial stages or in the late period);

- pathologies caused by subarachnoid hemorrhage in the brain (myocardial infarction, pulmonary edema, bleeding from a stomach or duodenal ulcer).

Among the long-term consequences of subarachnoid hemorrhage in the brain: memory disorders, attention, psycho-emotional disorders (depression, insomnia, agitation). Also, a standard complaint of patients who have suffered this condition is headache. Somewhat less frequently, hormonal disorders develop in the hypothalamic and pituitary gland systems.

General information

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a separate type of hemorrhagic stroke in which blood leaks into the subarachnoid (subarachnoid) space. The latter is located between the arachnoid (arachnoid) and soft cerebral membranes and contains cerebrospinal fluid. Blood poured into the subarachnoid space increases the volume of fluid contained in it, which leads to an increase in intracranial pressure. Irritation of the soft cerebral membrane occurs with the development of aseptic meningitis.

Vasospasm that occurs in response to bleeding can cause ischemia of certain areas of the brain with the occurrence of ischemic stroke or TIA. Subarachnoid hemorrhage accounts for about 10% of all strokes. Its frequency of occurrence per year varies from 6 to 20 cases per 100 thousand population. As a rule, SAH is diagnosed in people over 20 years of age, most often (up to 80% of cases) in the age range from 40 to 65 years.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

Diagnosis and treatment of subarachnoid cerebral hemorrhage

The doctor clarifies the victim’s medical history and conducts an external examination. The diagnosis is established on the basis of CT data, which makes it possible to determine the extent of the process, the presence of edema, and assess the condition of the cerebrospinal fluid system. If the results are negative, a lumbar puncture is performed.

MRI is a sensitive tool for diagnosing pathology after a few days. Vascular angiography is used to determine the source of bleeding in the brain.

Therapy for subarachnoid hemorrhage takes place in a neurological hospital and depends on the severity of the patient’s condition. It is aimed at solving the following problems:

- stabilization of the patient's condition;

- prevention of recurrent episode;

- normalization of homeostasis;

- treatment and prevention of ischemia, vascular spasm;

- therapy for the disease that caused the hemorrhage.

The aneurysm is clipped or endovascular occlusion is performed. Vasospasm and ischemia are treated with medication. In case of local spasm of a vessel, a vasodilator drug is injected directly into it or balloon angioplasty is performed.

In 50% of cases, subarachnoid hemorrhage leads to death. The majority develop significant impairments in the functional activity of the brain.

You can get help with this pathology at the Department of Neurosurgery of the City Clinical Hospital named after. A.K. Eramishantseva. The clinic has modern diagnostic equipment and advanced equipment for performing complex operations.

Prognosis and prevention

In 15% of cases, subarachnoid hemorrhage ends in death even before medical care is provided. Mortality in the first month in patients with SAH reaches 30%. In coma, mortality is about 80%, in repeated SAH - 70%. Patients who survive often have residual neurological deficits. The prognosis is most favorable in cases where angiography fails to identify the source of bleeding. Apparently, in such cases, spontaneous closure of the vascular defect occurs due to its small size.

The probability of repeated hemorrhage every day of the first month remains at 1-2%. Subarachnoid hemorrhage of aneurysmal origin recurs in 17-26% of cases, with AVM - in 5% of cases, with SAH of other etiology - much less frequently. Prevention of SAH involves treatment of cerebrovascular pathologies, TBI and elimination of risk factors.

You can share your medical history of what helped you in the treatment of subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Hemorrhagic stroke

Hemorrhagic stroke - hemorrhage in the brain and/or subarachnoid space, occurs four to five times less often than ischemic stroke

- Etiology of hemorrhagic stroke

The main etiological factors of hemorrhagic stroke are hypertension, arterial hypertension, congenital and acquired arterial and arteriovenous aneurysms. Subdural and epidural hematomas are usually of traumatic origin. Less commonly, the cause of hemorrhagic stroke can be hemorrhagic diathesis, the use of anticoagulants, amyloid angiopathies, mycoses, tumors, and encephalitis.

The predominant localization of hematomas is the cerebral hemispheres (about 90% of parenchymal hemorrhages); in 10% of cases, damage to the brain stem or cerebellum is detected. In most cases, there is a rupture of the vessel, much less often - diapedetic hemorrhages.

The clinic of parenchymal hemorrhages has general cerebral and focal symptoms. The clinical picture of subarachnoid hemorrhages includes two main groups of symptoms: cerebral and meningeal. In the presence of these and focal symptoms, we are talking about subarachnoid-parenchymal hemorrhage. Features of the clinical picture of parenchymal hemorrhages depend on the location of the hematoma.

- Hemorrhagic Stroke Clinic

Parenchymal hemorrhages. Hemorrhage into the putamen occurs with severe impairment of consciousness and a neurological defect in the form of contralateral hemiplegia, hemianesthesia, aphasia (with damage to the dominant hemisphere) or spatial hemiagnosia and anosognosia (with damage to the non-dominant hemisphere). The clinical picture is similar to that of middle cerebral artery occlusion.

With hemorrhages in the thalamus, as well as with hemorrhages in the putamen, herniation and coma are possible. Important signs of thalamic damage are greater severity of sensory disorders than motor ones, and unusual oculomotor disorders, often in the form of limited gaze, strabismus.

Table 1. HUNT Scale (Henry JM Barnett, Stroke, 1986) | |

| Degree | Characteristic |

| 0 | Unruptured aneurysm |

| I | Asymptomatic or minimal headache and mild neck stiffness |

| I.A. | Absence of meningeal or cerebral symptoms, but presence of persistent neurological deficit |

| II | Moderate to severe headache, stiff neck; no neurological deficit other than cranial nerve palsy |

| III | Drowsiness, confusion (disorientation in time and space), or mild local deficits |

| IV | Stupor, moderate to profound hemiparesis, possible early decerebrate rigidity and autonomic disturbances |

| V | Deep coma, decerebrate rigidity and signs of agony |

Hemorrhage into the pons is usually characterized by early development of coma, pinpoint pupils that do not respond to light, and bilateral decerebrate rigidity.

Hemorrhage into the cerebellum is characterized by sudden dizziness, vomiting in combination with severe ataxia, abasia, aesthesia and gaze paresis. Consciousness is not impaired, but compression of the trunk can lead to death.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage. Aneurysm rupture. Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is most often caused by the rupture of a saccular aneurysm, a defect in the internal elastic membrane of the arterial wall, usually occurring at the site of a bifurcation or branch of an artery. In most cases, the gap occurs between the ages of 35-65 years. There may be associated anomalies such as polycystic kidney disease or coarctation of the aorta. Sudden, unexplained headache of any location should raise suspicion of SAH and a computed tomography (CT) scan should be performed. For aneurysms larger than 7 mm, microsurgical obliteration is justified.

Another type of aneurysm is located along the internal carotid, vertebral or basilar artery; Depending on their structure, they are divided into fusiform, spherical and diffuse. Such aneurysms become clinically apparent when they put pressure on adjacent structures or due to thrombosis, but rarely rupture.

Table 2. Classes of social and everyday activity(Schmidt E.V., Makinsky T.A., Research Institute of Neurology, 1979) | |

| I | Return to work and complete independence from others |

| II | Return to work with limitations, independence in activities of daily living, walking without assistance |

| III | Limitation of previous household duties, partial dependence on others in everyday life, walking around the apartment without assistance, walking down the street with assistance |

| IV | The impossibility of returning patients who previously worked and suffered a stroke to work; for those who were engaged in housework, there is a significant limitation in the range of household duties or a complete inability to perform them, significant dependence on others in everyday life. Walking around the apartment with assistance. Sick people don't walk down the street |

| V | Complete loss of any productive activity. Complete dependence on others in everyday life |

A ruptured aneurysm is characterized by a sudden, intense headache. The patient usually says that he has never experienced such a severe headache before. Possible loss of consciousness; sometimes it turns into a coma, but more often consciousness is restored, although stupor remains. In some cases, loss of consciousness occurs suddenly, before the headache appears. SAH often occurs during exercise. When an aneurysm ruptures, the diagnosis is usually simple, but sometimes at an early stage there are no objective symptoms, so if there is a sudden headache, the doctor must think about subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Meningeal symptoms and low-grade fever are often present. Ophthalmoscopy often reveals subhyaloid hemorrhages.

Hemorrhage may be limited to the subarachnoid space or spread to the brain, causing focal symptoms. Sometimes, soon after hemorrhage, an ischemic stroke develops due to impaired blood flow or thrombosis in the arteries affected by the aneurysm.

It is not easy to determine the location of an aneurysm clinically, although it is sometimes possible. Thus, pain in the depths of the orbit and damage to the II-VI cranial nerves indicate an aneurysm of the cavernous part of the carotid artery; hemiplegia, aphasia and a number of other symptoms - for an aneurysm of the middle cerebral artery; damage to the third cranial nerve - an aneurysm at the junction of the posterior communicating and internal carotid arteries; abulia and weakness in the leg - due to an aneurysm of the anterior communicating artery; damage to the lower cranial nerves - an aneurysm of the basilar or vertebral artery.

A transient or persistent focal neurological defect that develops several days after a stroke is usually caused by a spasm of cerebral vessels that occurs in response to blood entering the subarachnoid space. Both an early and late complication of SAH can be hydrocephalus, which sometimes requires ventricular bypass.

Arteriovenous malformations. Arteriovenous malformations usually manifest as epileptic seizures or hemorrhage, but with large lesions, ischemia of adjacent areas of the brain may occur due to large blood flow. Most often this is a combined parenchymal-subarachnoid hemorrhage. People usually suffer from arteriovenous malformations in childhood and adolescence. That is why, for persistent headaches at this age, listening in the area of the orbit, carotid artery, and mastoid process is necessary.

The presence of vascular murmurs in these areas is pathognomonic. In doubtful cases, as well as for the purpose of differential diagnosis of telangiectasia and other angiomas, a CT scan can be done.

- Diagnosis of hemorrhagic stroke

CT is the method of choice. It allows not only to confirm the diagnosis, but also to determine the extent of the lesion in intracerebral parenchymal hemorrhages. CT is the best method for diagnosing SAH, and in most cases reveals blood in the subarachnoid space. This method also makes it possible to diagnose cerebral edema, parenchymal and intraventricular hemorrhage, and hydrocephalus. It is possible to identify the localization of the source in intrathecal hemorrhage.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) compared to CT is more reliable in diagnosing small hematomas localized in the pons and medulla oblongata, as well as hematomas in which the X-ray density of blood clots inside is equal to the density of brain tissue. MRI also makes it possible to identify arteriovenous malformations that are accessible to surgical intervention, which are very difficult to diagnose with CT, especially without contrast enhancement.

Cerebrospinal fluid examination is indicated only in cases where computed tomography is not available. Blood in the cerebrospinal fluid is detected in all cases of SAH, as well as with hemorrhages in the cerebellum and pons; with minor hemorrhages in the putamen and thalamus, red blood cells may appear in the cerebrospinal fluid only after 2-3 days.

X-ray of the skull reveals calcified malformations and aneurysms. As a rule, it is not carried out.

Cerebral angiography is usually performed immediately before surgery to clarify the location and anatomical nature of the aneurysm, as well as to confirm the presence or absence of focal cerebral vagospasm. In severe cases, angiography is best performed only when the diagnosis is unclear and especially when surgical decompression is indicated.

- Differential diagnosis of strokes

Cerebral crises precede cerebral hemorrhage; the disease begins violently, suddenly, often during the day due to physical stress or excitement. Precursors are characteristic (flushing to the face, headache, seeing objects in red); prolonged comatose states develop (sometimes several days); the face is hyperemic; temperature rises; breathing is bubbling, hoarse; pulse intense, rare; accent of the second tone at the top; blood pressure is increased; miosis or mydriasis on the side of the lesion; focal symptoms are identified in the form of rapid development of hemiplegia with a decrease in muscle tone, reflexes, and skin temperature; sometimes epileptiform seizures or early contractures (tonic spasms, protective hyperreflexia) occur; pronounced meningeal phenomena, brainstem disorders (breathing disorders, vomiting, floating movements of the eyeballs); pseudobulbar reflexes are rarely detected, urinary retention or incontinence is observed; retinal hemorrhages are visible in the fundus; cerebrospinal fluid is hemorrhagic, xanthochromic, pressure is increased; leukocytosis in the blood, prothrombin is not increased; in the urine there are red blood cells, sometimes sugar and protein.

Ischemic thrombotic stroke is preceded by transient cerebrovascular accidents. The disease develops gradually, more often at night, in the morning or during sleep; there are warning signs (dizziness, short-term disturbances of consciousness); characterized by incomplete or short-term loss of consciousness; the patient's face is pale, the temperature usually does not rise; slow breathing, weak pulse; heart sounds are muffled; blood pressure is not elevated; the size of the pupils most often does not change; focal symptoms appear in the form of hemiplegia or monoplegia with low muscle tone, one-sided Babinski reflex; hemiplegia develops gradually and is unstable; epileptiform seizures are not typical; there are no meningeal phenomena; stem phenomena are rarely observed (with extensive foci); with repeated strokes, pseudobulbar reflexes occur; sometimes there is urinary incontinence; narrowing and unevenness of blood vessels are visible in the fundus; the cerebrospinal fluid is clear, the pressure is normal; hypercoagulation is detected in the blood; urine specific gravity is low.

Non-thrombotic ischemic stroke is preceded by crises, angina, myocardial infarction, etc.; the disease develops suddenly during the day, more often after physical activity; often without warning; characterized by short-term loss of consciousness, stupor; the face is pale; the temperature is elevated; weakened, slow breathing; pulse is arrhythmic, weakened; muffled heart sounds, sometimes atrial fibrillation; blood pressure is low, pupils are constricted; transient hemiplegia develops with mildly increased muscle tone and a one-sided Babinski reflex; epileptiform seizures are rare; meningeal and stem phenomena are rare; pseudobulbar reflexes are often detected; there is urinary incontinence; sclerosis and narrowing of retinal vessels are visible in the fundus; cerebrospinal fluid is clear, its pressure is sometimes increased; Prothrombin is increased in the blood, traces of protein are detected in the urine.

- Treatment of hemorrhagic stroke

General principles. Along with differentiated therapy for hemorrhagic stroke, basic therapy aimed at maintaining vital body functions plays an important role. The more severe the course of the stroke, the more necessary is multilateral and complex basic therapy, which is carried out individually, under the control of laboratory parameters and the functions of all organs and systems.

In connection with modern pathogenetic concepts, early diagnosis of cerebral stroke, clarification of its nature and organization of emergency medical care at the prehospital and hospital stages are of particular importance. The effectiveness of treatment measures depends on the timeliness of their initiation and on the continuity of therapy in all periods of the disease.

The continuity of treatment measures is determined by the general tactics of patient management and is associated with solving organizational problems: rapid transportation of the patient, clear organization of the work of the emergency department; early clarification of the diagnosis and resolution of the issue of referral to the appropriate department; smooth operation of all levels of assistance.

Neurosurgical intervention. The problem of hemorrhagic stroke, according to most researchers, is largely neurosurgical. If ischemic stroke is a process of development of hemodynamic and metabolic changes, ending mainly a few days after an acute cerebrovascular accident, then hemorrhagic stroke is a fait accompli of hemorrhage, and its pathogenesis involves secondary phenomena of already shed blood.

Removal of a hematoma after an intracerebral hemorrhage, if it is localized in an accessible area of the brain (for example, in the cerebellum, putamen, thalamus, or temporal lobe), can save the patient's life. The operation is indicated as early as possible (24-48 hours) for aneurysm ruptures, if the patient’s condition does not improve and signs of herniation appear. The main operation is clipping the neck of the aneurysm; wrapping the aneurysm with muscle or, less commonly, extracranial occlusion of the internal carotid artery is also performed.

Patients whose condition corresponds to grade 0 - III on the Hunt scale have no contraindications on this scale for hospitalization in the neurosurgical department (Table 1).

Differentiated conservative therapy. Conservative therapeutic interventions for hemorrhagic stroke should be aimed at rapid correction of blood pressure to optimal values for a particular patient; to combat developing cerebral edema and to carry out hemostatic and vascular wall-strengthening therapy.

Correction and control of blood pressure. If possible, blood pressure (BP) should be avoided. They try to keep the blood pressure within normal limits using antihypertensive drugs (beta blockers, calcium antagonists, antispasmodics, ACE inhibitors). To prevent emotional reactions, sedative therapy (diazepam, elenium) is prescribed. Sometimes phenobarbital is prescribed for prophylactic purposes (30 mg orally three times a day), since it also has an anticonvulsant effect.

To avoid straining, laxatives (regulax, glaxena, senade, etc.) are prescribed. It is necessary to create conditions for “protective inhibition”; protect from light and noise.

Hemostatic therapy and therapy aimed at strengthening the vascular wall. Prescribe dicinone (sodium ethmazilate) intravenously or intramuscularly (250 mg four times a day); antiprotease drugs for 5-10 days: gordox (100 thousand units four times a day intravenously) or contrical (30 thousand units immediately, and then 10 thousand units twice a day intravenously).

Calcium preparations (calcium pantothenate, berrocca, calcium gluconate - i.m., calcium chloride - i.v.), rutin, vikasol, ascorbic acid strengthen the vascular wall well.

Antifibrinolytic therapy in the form of gamma-aminocaproic acid up to 30 g per day (100-150 ml of a 5% solution intravenously, then orally) is of great importance. It can be administered with small doses of rheopolyglucin, which improves microcirculation.

Fighting cerebral edema. If lethargy or signs of herniation appear, it is better to prescribe osmotic diuretics mannitol (0.5 - 1.5 g/kg of the patient’s body weight, IV) or glycerin (1 g/kg orally). Less commonly prescribed corticosteroids are dexazone according to the scheme (8+4+4+4 mg IV). More effective are Lasix (20 mg IV twice a day) and/or Reogluman (200 ml IV drip twice a day).

Treatment of spasm of cerebral vessels. Signs of cerebral vasospasm (drowsiness, focal symptoms) appear after two to three days and most often on the seventh day after a hemorrhagic stroke. It is believed to be caused by the release of serotonin, catecholamines, peptides and other vasoactive substances. Prescribed for spasms, and even better for preventive purposes in advance. Calcium antagonists - nimoton (10 mg IV drip) - 10-14 days or nimodipine (30-60 mg orally every four hours). In this case, correction of antihypertensive therapy is necessary, since calcium antagonists affect blood pressure.

Rehabilitation treatment. Rehabilitation therapy is carried out over a long period of time and at all stages of treatment, but it is especially important after the acute period of a stroke. Physiotherapy exercises are combined with physiotherapy, acupressure and classical massage, acupuncture, electrical stimulation, and magnetotherapy.

Occupational therapy is required - training in self-care skills, work on training stands and work simulators. Psychotherapy is effective: individual, group, family; Autogenic, adaptive training, etc. are recommended. Speech therapy classes are required for persons with speech impairments.

The patient needs treatment for a total of at least three to four months. For severe strokes, depending on the patient’s condition, this period can be extended to six months or more. Patients are registered at the dispensary. With a prolonged period of restoration of functions, patients are transferred to disability.

- Work ability examination

Currently, there are five classes of social and everyday activity (Table 2).

The disability group is determined according to the severity of dysfunction and profession. Patients with paralysis of the limbs and aphasia need care from outsiders and are recognized as group I disabled people. In case of deep paresis, when the ability to self-care remains, but the ability to work is lost, disability group II is assigned. Group II patients adapt to working from home: typing, assembling parts, doing dispatch activities on the phone, etc.

Literature

1. Bogolepov N.K. Clinical lectures on neurology, 1971. 2. Internal diseases. Ed. Harrison T. R., vol. 10, 1997. 3. Gusev E. I., Skvortsova V. I., Chekneva N. S. et al. Treatment of acute cerebral stroke (diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms), M., 1997. 4. Allen GS, et al. Cerebral arterial spasm: A controlled trial of nimodipine in patients with subarachnoid hemorrage. //N. Engl. J. Med. 308:619, 1983. 5. Cerebral embolism study group. Brain hemorrhage and management options. Stroke 15:779, 1984. 6. Curling OD et al. An analysis of natural history of cavernosus angiomas. J Neurosurgery 75:702, 1991. 7. Henry JM, Barnett. Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. 1986. 8. Manual of Neurologic Therapeutics. Edited by Martin A. Samuels, MD 1995. 9. Nibbelink DW, Torner JC, Henderson WG Interactional aneurysms and subarachnoid hemorrage: A cooperative study. Antifibrinolytic therapy in recent onset subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 6:662, 1975. 10. Origitano TC et al. Sustained increased cerebral blood flow with prophylactic hypertensive hypervolemic hemodilution (“Triple-H Therapy”) after subarachnoid hemorrage. Neurosurgery 27:729, 1990. 11. Wilkins RH Natural History of Intracranial Vascular Information: A review. Neurosurg 16:421, 1985.